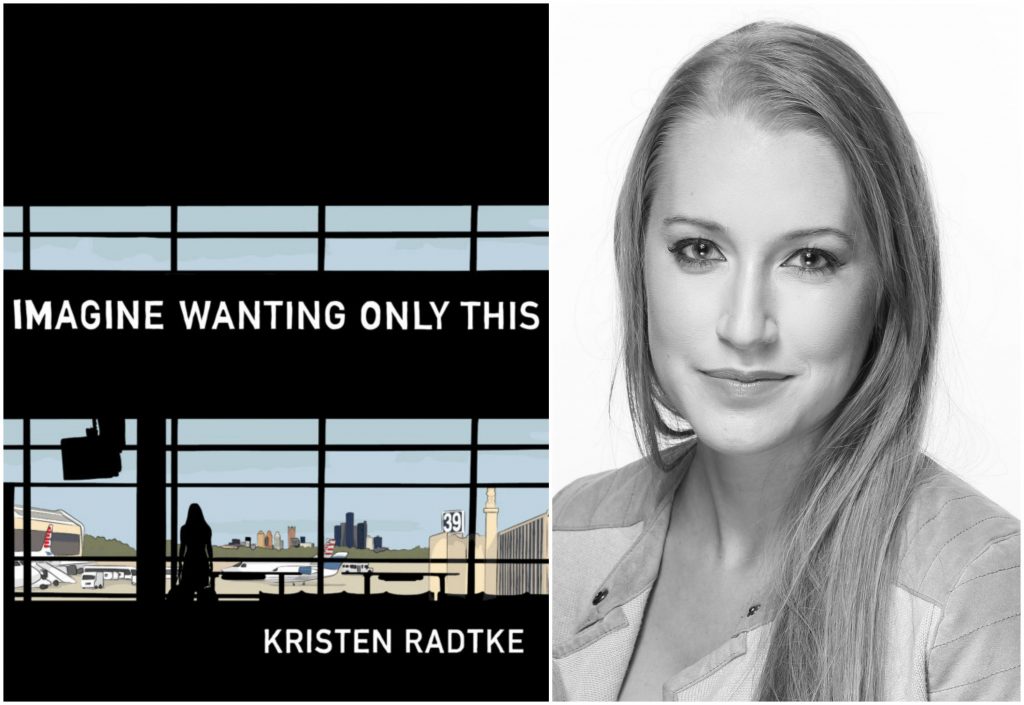

The notion of telling stories with pictures traces back to the cavemen. So, likely, do ruminations on loss, impermanence, and wanderlust. In Imagine Wanting Only This (Pantheon Books, April 2018), writer and illustrator Kristen Radtke fuses such time-tested themes and visual storytelling mechanisms with the more contemporary preoccupation that is environmental devastation. Radtke’s is a debut graphic memoir about modern-day ruins, forged from interior thought and visual imagination. Through masterful drawings and pithy, poetic text, she traces a narrative arc from her childhood in Wisconsin and the death of her beloved uncle to an apocalyptic — yet sadly realistic — vision of her current home, New York City, under water.

Throughout, Radtke reflects on the complexities of becoming an artist, and what it means when people and places are left behind. She traveled far and wide to document such “left behind” environs — an abandoned mining town near where her uncle’s widow lives in Colorado; the formerly bustling and now near-desolate steel-mill town of Gary, Indiana; a deserted military base on the Philippine island of Corregidor; and the ancient, abandoned cities of Angkor and the Roman Empire. Her renderings also re-imagine several natural catastrophes, including the site of the nation’s deadliest wildfire (Peshtigo, Wisconsin, in 1871); a volcanic eruption that wiped out a town in Heimaey, Iceland; and ultimately, climate scientists’ prediction of a wholly submerged New York City.

Throughout, Radtke reflects on the complexities of becoming an artist, and what it means when people and places are left behind. She traveled far and wide to document such “left behind” environs — an abandoned mining town near where her uncle’s widow lives in Colorado; the formerly bustling and now near-desolate steel-mill town of Gary, Indiana; a deserted military base on the Philippine island of Corregidor; and the ancient, abandoned cities of Angkor and the Roman Empire. Her renderings also re-imagine several natural catastrophes, including the site of the nation’s deadliest wildfire (Peshtigo, Wisconsin, in 1871); a volcanic eruption that wiped out a town in Heimaey, Iceland; and ultimately, climate scientists’ prediction of a wholly submerged New York City.

It’s not just for the sake of “ruin porn,” though — Radtke juxtaposes the fragility of these places with that of the human body, writing, “Someday there will be nothing left that you have touched.” It’s a haunting line that hits every touchstone of Imagine Wanting Only This — a coming-of-age story that is also a travelogue, and a rumination of both the literal and figurative varieties of devastation.

The author recently found time in her busy schedule (she works as the managing editor of Sarabande Books, and designs other authors’ book covers), to answer all my questions about how she arrived on this form, as well as her writing process, her sketching process, and how she merges the two.

Tell me about the moment you knew you needed to write this book.

I was writing essays for a long time about abandoned places in grad school, but I didn’t understand that it was a full project. I had a thesis requirement, and was trying to figure out what all my work had in common. A friend noticed I was always writing about aftermath, decay, and ruins — but I’d never seen all that as an essay collection. And I’d always been an illustrator, but I never put them [writing and drawings] together until my last semester in grad school. The first piece I drew is a very different, early version of one of the scenes with my uncle. And then this graphic memoir kind of slowly and arduously evolved from there.

Did you primarily identify as a writer, or as an illustrator?

Did you primarily identify as a writer, or as an illustrator?

I don’t know, and I can’t remember which first became part of my identity. I did newspaper in high school, but I was also always drawing — like, failing algebra because I was just sitting in the back, drawing — and for college I went to art school. I kind of resist the idea that there’s something I can do in one medium but not in another — I think that with stories, we can accomplish whatever we need to in either medium, and that it’s about employing whatever best communicates what you’re trying to say in that moment. I like drawing because it’s immediate — it hits us faster than prose writing. And I like pairing writing with images; you can get a sense of the background space and scene — stuff that wouldn’t necessarily move the narrative forward in standalone prose writing.

Tell me about the experience of illustrating your own stuff, as opposed to another author’s.

At first I didn’t want to design my own book cover work; I wanted my publisher to do it. It seemed crazy to be in control of packaging your own book. I feel like I’m constantly telling authors, You’ve done your part of the book; let me take it from here, and that’s how I felt, too, but my publisher felt pretty strongly that it should be me that did it — which I guess is the standard for comics artists, and that makes sense. But it was hard; unlike when I design other book covers, I didn’t have much of a sense of whether what I was doing was good.

What’s the editing process like when it comes to illustrations?

It’s just like editing words; at least, I think that’s how the best editors approach it. I worked closely to someone who responded to both my images and text. I like it when an editor can put pressure on decisions you make with text, and speak to how you balance that with art. I think that sometimes the risk for a graphic book is that during the editing process, people can be excited for its novelty, and therefore not as critical. You need someone who’s going to apply the same pressure and standard to the images. I will say I cut a lot more text — there was a ton more in earlier drafts. Because if you can say something in the form of illustrations, I kind of felt like I should. It was pretty laborious to figure out how not to say the same thing in both mediums.

Do you start with words, or images, or work on both at same time? Do you draw while you’re experiencing something, or do you draw from memory?

It depends, but I usually write first. When I’m gathering stories, I take photos, and I work later — I almost never am in a place recording that place. I just try to get down as much written information as I can. While I had visited all the places I wrote about in the book, I didn’t know I was working on a graphic project at the time, so it was hard to find some source material — I had to rely on a lot of archival photographs. Even to draw family members, I had to find photos of them at the age they were at that point in my story.

Who are greatest inspirations?

The obvious big one is Alison Bechdel—Fun Home taught me what a graphic memoir was, and I felt really moved by [Marjane Satrapi’s] Persepolis, too. But when I started this project, I can’t say I was super well-read when it came to graphic lit — I’d read Archie comics, and that was about it. Joan Didion was the person I read most in college and grad school and beyond, and I felt like she really informed the way I write nonfiction. Susan Steinberg, a fiction writer whose third collection, Spectacle, is being published at Graywolf, made me rethink the way I write sentences. She writes these short, staccato, no-frills ones that are startlingly beautiful.

Do you feel the field of graphic literature for women has changed since 2004, when Charles McGrath famously wrote in the New York Times Magazine that the graphic novel was a man’s world?

I don’t think it’s changed. Even just the other day, I saw that someone had reviewed me on Goodreads; it was a flattering review, but they said, I was expecting this to just be some girl comic. Which tells me the immediate reaction is that it would be very non-literary. The graphic novels and memoirs that get taken most seriously are still by men. With Alison [Bechdel], people still say, Oh, it’s her story, vs. [author of the graphic novel Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth] Chris Ware’s “art.”

What’s next for you?

I’m working on two more projects — a series for the New Yorker’s “Page Turner” section about urban loneliness. It’s more illustration than text — a series of drawings of people publicly alone in New York. I’m always really interested in people who are by themselves in alleys and parking lots; say, having distraught conversations on their phones — I mean, who goes out to the parking lot to have cheery conversations? I’ve trolled the city for these subjects — I also have a series of people falling asleep on the subway. And then I’m also working on a full book project, a graphic novel. That one’s year’s down the road, but I do know it’ll be in color. I feel ready to step away from nonfiction for just a little bit.

Now that you’ve put this nonfiction out into the world, are you still drawn to abandoned places, or, as you put it in the book, driven by “ruin lust”?

I don’t really know. I feel like I’m drawn to them in the same way everyone is — there’s something terrifying but beautiful about ruins, especially contemporary ruins, and we all just want to see what happens next in those places. I’ve always been wanderlusty and restless, and this project was a big catalyst to really explore that side of myself.

Imagine Wanting Only This is available through Pantheon Books, and through Amazon.

Author photo by Greg Salvatori.