The big exhibition space on the sixth floor of the Museum of Modern Art right now is given over to the work of Francis Picabia, an artist born in Paris in 1879 to a French mother and Cuban father. I dutifully made my art historical pilgrimage to see his works on display at MoMA, from my home in Washington Heights to the bowels of Midtown, close enough to the president-elect’s part of Manhattan that the museum might consider adding a trigger warning on their website. But I did not slog through the throngs of pre-Christmas crowds gathered for window gawking on 5th Avenue and ice skating at Rockefeller Center to see Picabia’s paintings, for which he is most famous; I came for the Dada magazines he made. These often large-format, textually sparse, and brilliantly illustrated publications offer a playful vision of a mechanical future so specific to the early twentieth-century, for which I am a total, and everlasting, sucker.

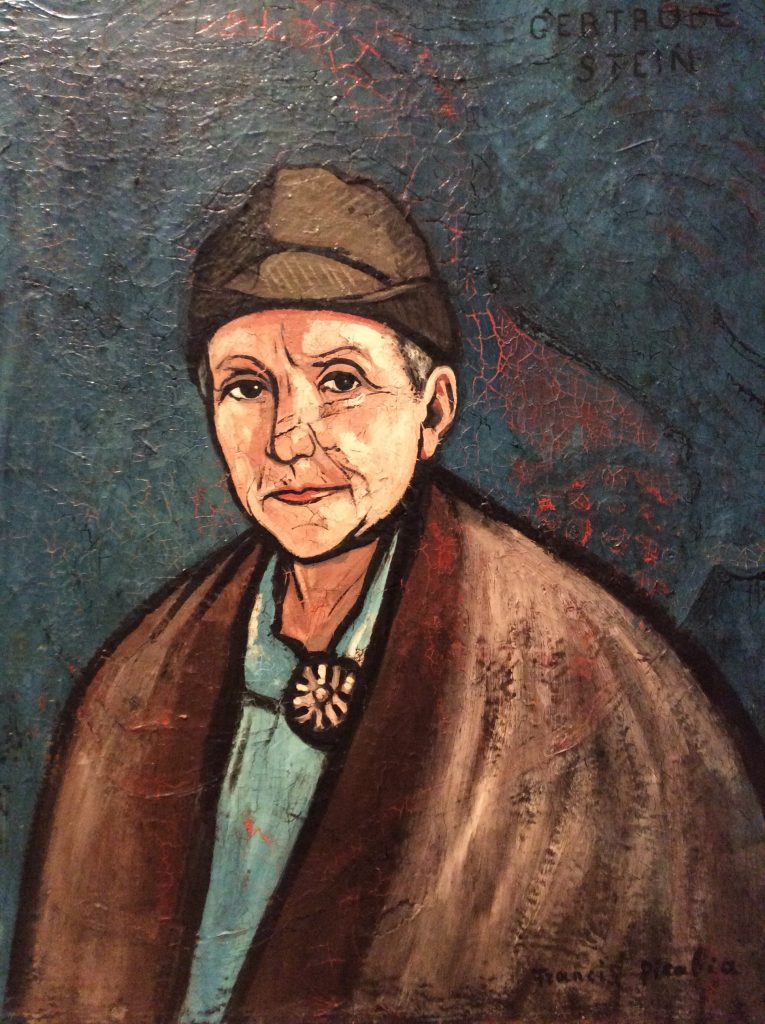

And yet it would in fact turn out to be a painting that stole the show for me in that exhibition: a not-particularly huge canvas, framed in black, situated in a corner towards the exit. The oil paint is thick and cracking. In dark blues and browns and reds, it is a portrait of Gertrude Stein.

I’ve never seen the author of Tender Buttons and Three Lives look as she looks in this painting by Picabia from 1937. Her head is small, perched on wide and rounded shoulders draped in brown. Beneath the cloak, a soft blue blouse with a large brooch peeks through. On her face, a sort of “oh well” smirk on thin, taut lips. Her nose is long and slender and her almond eyes look left, registering a low level of concern. A jaunty cap mostly covers her greying hair. In this painting, she is resigned and resplendent; she is also imbued with a particularly feminine sort of beautiful. And with Gertrude, this is not so oft a thing. I love renderings of Stein of more ambiguous gender and sterner features, such as in the photographs of Man Ray, but Picabia’s portrait drew my attention precisely because it was a side of the writer I’d not seen before.

It was surprising to see Gertrude in such softness, painted in the early years of Nazi rule in Germany, and just before the outbreak of World War II. Even in an earlier portrait by Picabia from 1933, Stein looks more masculine and severe, almost militarized, sitting in a Roman tunic facing the viewer straight on and confrontationally, eyes rolled towards the sky, hair cropped short. Stein is known to have had Nazi sympathies, and managed to stay in France with her partner Alice B. Toklas during World War II under the protection of Bernard Faÿ, a Vichy collaborator. A Jew and a woman, Stein was not so kind to either group in her life and writing.

In Stein’s 1933 autobiography masked as biography via the purported autobiography of Toklas (The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas), the author tells of dinner parties in Paris in which she sat with the men — the “geniuses” — and in which her female partner was relegated to the wives’ table. Inhabiting the perspective of Toklas, Stein writes:

Before I decided to write this book my twenty-five years with Gertrude Stein, I had often said that I would write, The wives of geniuses I have sat with. I have sat with so many. I have sat with wives who were not wives, of geniuses who were real geniuses. I have sat with real wives of geniuses who were not real geniuses. I have sat with wives of geniuses, of near geniuses, of would be geniuses, in short I have sat very often and very long with many wives and wives of many geniuses.

Regardless of the permutation, one thing is constant: the geniuses are men; the wives are women. Stein only allows an exception to this rule in her own particular case, and, as the singular female genius, she does not entertain the same possibility in other women. She continues:

As I was saying, Fernande, who was then living with Picasso and had been with him a long time that is to say they were all twenty-four years old at that time but they had been together a long time, Fernande was the first wife of a genius I sat with and she was not the least amusing. We talked hats.

Stein sat for portraits made by many of these “geniuses,” the first and perhaps most famous by Pablo Picasso, in 1905-06. In The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Stein writes often and proudly of the Picasso portrait (which was bequeathed to the Met upon her death in 1946).  Stein recalls an early sitting, in which her friends and family looked upon the work in progress and “begged and begged that it should be left as it was. But Picasso shook his head and said, non.” What would come to be is a study in browns, of a slightly slouched Stein, looking pensive and regal with those almond eyes and pointed nose, her hair not yet cut short but “worn […] as a crown on the top of her head.”

Stein recalls an early sitting, in which her friends and family looked upon the work in progress and “begged and begged that it should be left as it was. But Picasso shook his head and said, non.” What would come to be is a study in browns, of a slightly slouched Stein, looking pensive and regal with those almond eyes and pointed nose, her hair not yet cut short but “worn […] as a crown on the top of her head.”

In The Autobiography, Stein-as-Toklas writes, “After a little while I murmured to Picasso that I liked his portrait of Gertrude Stein. Yes, he said, everybody says that she does not look like it but that does not make any difference, she will, he said.” (Picasso, in Stein’s telling, seems to have forever been mediating Stein in real life via the Stein he himself had painted. Elsewhere in The Autobiography, Stein recalls “another charming story of the portrait” in which Picasso comes up to her at a gathering after she has cut her hair to what would become her signature crop: “approaching her [he] quickly called out, Gertrude, what is it, what is it. What is what, Pablo, she said. Let me see, he said. She let him see. And my portrait, said he sternly. Then his face softening he added, mais, quand même tout y est, all the same it is all there.”)

Gertrude Stein loved not only to sit for portraits, but to make her own. In The Autobiography, describing a period in the years before World War I, she writes:

This was the beginning of the long series of portraits. She has written portraits of practically everybody she has known, and written them in all manners and in all styles. Ada was followed by portraits of Matisse and Picasso, and Stieglitz who was much interested in them and Gertrude Stein printed them in a special number of Camera Work. She then began to do short portraits of everybody who came in and out. […] Everybody was given their portrait to read and they were all pleased and it was all very amusing. All of this occupied a great deal of that winter and then we went to Spain.

The publication of these portraits by Alfred Stieglitz (who also collaborated with Picabia around the same period) in his art magazine Camera Work suggests the photographic perspicacity in her prose. Stein’s portraits of Matisse and Picasso printed there in 1912 were the first of here writings to appear in an American publication.

The portrait is central to Stein’s body of work; it appears in her own writing and in the renderings of her by the “geniuses” with which she surrounded herself, over and again. Stein’s life and image are alluring, and it is no wonder so many have tried to capture it. But it is difficult to paint a true picture of Stein. Structuralism would have us separate the biography from the work of the author, but with Stein, when the biography is so often the work itself, that is not so easily done. So I struggle to hold my admiration for this woman’s work, made among men and in her own image, alongside all the unpleasant truths of the woman herself.

But somehow the Picabia portrait at MoMA allows me in looking, just for that moment, only to love.

*

Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through March 19, 2017.

Lead image: Picabia, Francis. “Gertrude Stein.” 1937. Oil on canvas. Galerie Haas, Zurich.

Inset image: Picasso, Pablo. “Gertrude Stein.” 1905-06. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York.