What are your dreams for the future? For the Earth, for yourself, for generations to come? What values do you want to live on, and what phantoms of 2016 do you hope will go extinct?

Imagine breathing the air of twenty, thirty, forty years from now. In this future (as in our present, arguably), what might the consequences be if the more we kept connecting through technology, the less connected we felt to humanity? Have our decades-long chains of accelerating change, conquering expanses, overworking ourselves, and embracing the loneliest ways of being “social” exhausted our spirits?

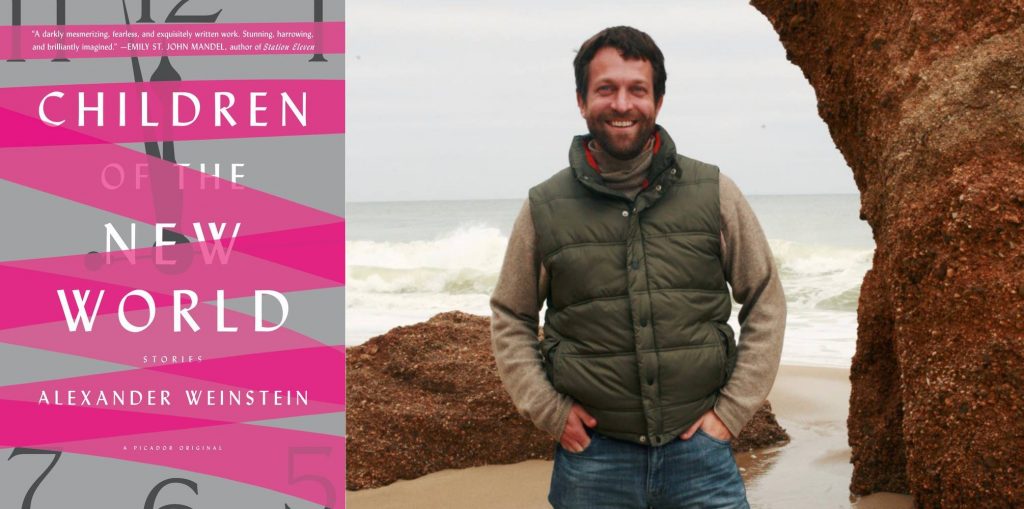

In his breakthrough collection of near-future-set dystopian short stories, Children of the New World (Picador, 2016), Alexander Weinstein takes on all these questions and more through an evocative whirlwind of gutting fiction. Alexander describes in his must-watch Talk at Google the catalyst for starting Children of the New World ten years ago: a realization that many humans were becoming emotionally attached to technology (i.e. when people say I love my phone or I couldn’t live without my phone). “Technology exacerbates opportunities for loneliness,” Weinstein says. It’s this externally-connected, internally-disconnected state of being that sets the premise for a society eerily similar to ours today–one in which a devastating chronology begins with the first story in Children of the New World.

“What if we had technologies that helped us transcend our egos?” Alexander asks in his Google Talk. Perhaps, consciously or not, we’ve been pursuing elsewhere for too long the essence of what’s been waiting patiently within us all along. Maybe now, together, we need to undo.

I recently had the opportunity to ask Weinstein my most pressing questions about his book and for his thoughts on the future of our society given the high-tech, fast-paced present reality. His responses are vital, inspiring, and relevant, ripe for us at this moment in time.

Congratulations on your debut book, Children of the New World. I enjoyed it immensely, and it also terrified me. The collection offers a look into our future from the starting point of our current cultural, emotional, technological trajectory. How can we change or transcend the path we’re on now to prevent your fictional future from becoming reality? What do we humans need to move forward in a more sustainable, positive direction?

It’s a question I think a great deal about — especially as my fiction becomes reality (recently I heard they’re working on eye-screen contact lenses and temporary digital tattoos which will allow us to carry our interface on our bodies). I think one step towards preventing the futures I write about is for us to become less attached to our devices. Right now we’re in the binge drinking stage of technological addiction. There are emails to check, Facebook posts to like, Instagram photos to upload, Tinder/Grinder profiles to swipe, emojis to learn, and endless text messages. I find myself checking my phone five times a day — twenty, thirty. At stoplights, I see other drivers, sending off one more message before the light turns green. Next to us in the restaurant is a family eating dinner in silence as they individually play with their smartphones. And at bus stops around the world, grown men and women are playing tiny games on their screens like children.

So the first step of recovery is acknowledging we’ve become addicted. From there I think we’ll need to take concrete steps towards recovery. Going for a walk down the street without checking our phones, leaving our smartphones at home, calling instead of texting, meeting romantic partners by going out to social gathering rather than logging onto social networks. This will likely sound/feel Luddite to many, and for those of us attempting this feat, I imagine we’ll get the itch to launch angry birds at pigs every now and again, but I believe it’ll be the start of reconnecting with ourselves and each other. We’ll rediscover things like gardening, dinner parties, even merely the ability to sit alone at a café and look out a window with contentment again.

The near-demise of the spirit of humanity seems to be directly connected to humans’ own devaluation of love (a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy). What role can you see technology (social media in particular) playing as it develops not to overthrow in-person connection but to supplement it more naturally/effortlessly as it was intended? What are your hopes for what the future might look like given humanity’s ever-improving technological capability and capacity for both goodness/sanity and evil/madness?

I was recently asked a variation of this question at a talk I gave at Google: What kind of technology could I envision that would help humanity? I tend to think that the most basic answer to this question is: technology to help create clean drinking water, and clean energy technologies which can supplant oil and coal, etc. So essentially, functional technology whose aim is to solve our most fundamental environmental problems.

As for the social level — I’ve been envisioning a vast network of social care organizations which are funded by celebrities, sports stars, CEO benefactors, etc. Essentially it’d be creating a kind of second society — one wherein benefactors contributed towards causes they felt strongly about (arts programs in the community, universal healthcare, free education, after-school sports programs, homeless shelters, community gardens) and individuals could sign up and contribute to this network. It would be a highly organized and elaborate nonprofit which created a socioeconomic system akin to Denmark, The Netherlands, France, etc. As an individual, I could pay a certain amount towards this system and then get the benefits of health care, free education for my children, etc. If I fell below a certain income bracket, I could get these benefits for free.

For something this massive to work, it would require a huge amount of interconnection between benefactors, individuals, and the already established nonprofit and community organizations which need funding. Until I visited Google, I thought: yes, but this idea is simply too massive to organize and oversee. However, it occurred to me that this kind of vast organization is precisely what places like Google and Yahoo already have. So I suppose, if you’re asking me to dream big, I envision that these tech companies might turn their attention towards becoming a kind of second-socioeconomic system, working towards the benefits of clean energy, world hunger, universal health care, free education, and social justice rather than marketing.

You describe your book as humor-based and hopeful for humanity. What role do you think humor plays in literature for getting across serious messages to a perhaps otherwise apathetic audience?

Humor helps the heart to open. And heartfelt laughter leads us towards greater connection with those around us. If you can find a way to share humor with others, then there’s an openness towards greater listening and compassion. With the serious topics I write about (environmental collapse, corporate avarice, western colonialism, electronic isolation, etc.) there’s a way such stories can calcify the heart if one isn’t careful. I noticed this in my teaching — if I’m just giving my students the disturbing facts about humanity without humor, it can lead to depression, discouragement, and a deeper political/social apathy. So, humor seems to restore our humanity to us — it allows us to deal with suffering with a more open heart.

In “Migration,” the character Max wears a hockey mask as he rides his bike to Toys “R” Us, and after his father finds him, as the two spot the majestic deer, Max says, “Wow,” to which his father replies, “I know.” With these tiny three words of dialogue, you say so much about the differing levels of hope and disillusionment between the generations. As we all get older, how do you think we can maintain the childlike “wow” reaction?

Maintaining the childlike “wow” is a general life goal for me. I find that my teaching often revolves around this critical skill. I teach a course called Contemplation and Action, where alongside contemplative practices like meditation, yoga, and eastern spirituality, we practice dance, theater, art, and song. It’s amazing to see how many of these childhood joys students have already lost by the age of eighteen. As we grow into adults, we somehow leave these wonderful aspects of life behind. We become afraid of our voices and so we no longer sing, we think we’re awful artists and so we don’t draw anymore, we move in very scripted and socially accepted ways rather than exploring the range of dance and movement which we once did as children. I see this as a great loss — one which echoes the demands of a society that values commodification and efficiency rather than creativity and play.

So, in my classes, we begin to dance again, and to sing, and to make art — and over time, the students begin to open up and find they love these things which they abandoned way back in grade school. I have one exercise that I do during the autumn. On one of those beautiful days when it’s raining leaves, we go outside as a class and practice a game of trying to catch the most leaves before they hit the ground. It’s amazing to see the immediate return to play that happens. Suddenly all these rather serious athletes, math majors, nursing students, and business kids are running around and playing again, their voices ringing through the fall day. There’s a lightness to the group, they’re laughing again, and for a moment they’ve returned to that sense of play inherent within us.

So these kinds of exercises can help return us to our childhood sense of wonder. There are of course many other methods too: falling in love, becoming a parent, getting out into nature, meditating, psychedelics, hiking, etc. are all powerful ways to rediscover what it means to be alive.

In the titular story “Children of the New World,” the character Bill says, “‘We all have to reboot this,’ … he motions to the room with his open palms, ‘This world, with all its pain and loss. This is where we learn to love again.’” I love how at the end he notes, “Human contact is all there really is.” If rebooting isn’t an option, where do we go from here to heal our inherent viruses and better our natural and societal environment?

Compassion and empathy seem a good place to start. Helping out wherever and however you can. This is difficult because I think many of us feel economically pressed these days. We are working two to three jobs, there are daily needs to see to, we barely have time for ourselves it seems. Adding to this is the inherent narcissism involved in our devices (we spend our free time putting filters onto photos so to post highlights from our lives onto social networks, ad infinitum). So, again, I think getting away from our devices and finding ways to re-engage with community is vital. There are a great deal of people suffering, and a great many ways to volunteer our time to help others. To do this means to begin to shrug off the gospel of survival-of-the-fittest capitalism and extend our time and resources to help others have a better life. It’s a big task, but I think this is the human reboot that can help our world become a better place.

Elon Musk has referred to humans creating artificial intelligence as “summoning the demon.” In “Saying Goodbye to Yang,” we get the sense that Yang is a truly helpful robot and close with his human family. What are your thoughts on AI, and how do you hope humans can be proactively practical about developing future technologies for society?

Yang is a nice “boy” and a very good-hearted robot. That said, I’m completely terrified of him! I’m not a big fan of AI technology, even down to Siri on my phone. I mean, it’s nice that I have someone to talk to these days, but I find Siri creepy. There’s great interest in AI and robotics to make our lives easier (note how technology is always selling us on new advances with this line: it’ll make your life easier!). But I think going down the AI road is a big mistake. We’ve barely scratched the surface of what it means to be human. I don’t think we’re in the best position to create alternate non-human intelligences.

What was the writing process like for you? Is there a specific place or time of day where or when you feel most productive?

I tend to always have paper close at hand — because I find that when stories suddenly “bite” I want to get them onto land as soon as possible. I write by hand first — it allows me to be much looser and more experimental in the first draft. This way, I can make a mess on the page without worrying about it. Then I take each story from the handwritten page to the computer, and from there I’m usually drafting/revising/editing the piece anywhere from eight to a dozen times. My stories take six months to a year to reach completion. Luckily, I have at least four or five stories working at a time, all in various stages of completion, so I don’t really notice how long it takes for each story’s gestation period.

I also have a habit of stopping whatever I’m doing when I get a story idea, and writing for as long as I can. This might mean that if I’m driving, I have to pull over to the side of the road (somewhere safe) and write for an hour. Or I might be getting ready to go to sleep — and I’ll have a flash of the plot of a short story. Rather than go to sleep, I’ll turn the light back on, get out my journal and begin writing (sometimes for the next two to three hours) even though I have to teach class in the morning.

Being at home tends to be my ideal. I don’t usually enjoy writing in coffee shops or in public — I find it too distracting. That said, as I’ve been working on my new book, The Lost Traveler’s Tour Guide, I’ve been writing in public places while traveling. The book is comprised of tour guide entries that describe fantastical cities, museums, libraries, restaurants, hotels, and art galleries — each one a universe unto itself. Since the format is a fictional tour guide, traveling and being out in public seems to be aiding my process.

The final story of your collection, “Ice Age,” ends with the line, “drunken men, spoiling what once was our community.” This seems to sum up the warning underneath the future realism stories of Children of the New World. Spiritual teacher Barry Long once said, “The future will be not man’s world, not woman’s world, but love’s world. The only hope is woman.” As stewards of good nature and love on this planet, what do you believe women can do to prevent humanity from the likely futures depicted in your book?

I really like this question, and it’s a deeply complicated one. There’s certainly a brand of American masculinity which I find abhorrent. This is the privileged, white male, drunken frat brother/bro-dog, business-major mentality — an ideology full of classism, racism, misogyny, homophobia, privilege, rape-culture, xenophobia, and relentless narcissism. And while there are plenty of business majors, frat brothers, and sports fanatics who are wonderful people, these particular groups do seem to nurture this particular brand of ugly American masculinity. You spot these folks during football season in college towns — white dude-bros with their shirts off, hooting and hollering at passing women and cars, with the entitled belief that the world belongs to them. These are the kind of men who think feminism is a bad word, that men are naturally the head of the household, and that the world is separated between the weak and the strong. Behind this mentality is a lineage of white colonialism and male privilege, one which deeply disturbs me. And it’s this toxic form of masculinity that I’m referencing in Ice Age.

The history of misogyny is clear: women and their rights have been aggressively suppressed throughout human history by men. Patriarchy is an ugly beast, one which is systematically destroying the world socially, economically, politically, and environmentally. And I have a lot of hope for a future which embraces feminism, one wherein a feminist sensibility gets to lead us for a long time. Because, frankly, men have historically fucked up the world.

The real difference, as I see it, is about systems of ideology. If we’re to be somewhat rudimentary, on one side you have the power-hungry cosmology which is interested in hierarchies of power, domination, authoritarianism, exploiting nature and humans, puritanism, orthodoxy, brute force, war, survival-of-the-fittest capitalism, and harbors a lack of appreciation for the arts and the erotic. On the other side, you have an ideology which believes in cooperation and compassion, stewardship of the Earth, helping those in need, group thinking and communal experience, peace, art, creativity, the erotic, and caring for nature and human justice. And both men and women can fall into either camp of ideology. So, I believe that supporting this second life-nurturing ideology, and identifying and constantly refuting the domination-ideology, is the way we will create a much better future.

Perhaps a more accurate way to categorize the particular destructive ideology we’re talking about is one which Ginsberg discusses in his epic poem “Howl.” Ginsberg terms it Moloch the destroyer, with its fingers of armies, and its mind of pure machinery. He’s speaking of the corporate-empire builders. The challenge then, is to overcome these internal and external ideological power-hungry demons — something that, as a culture, we haven’t seemed capable of yet. “Ice Age” ends with that statement about drunken men ruining what was the community, because they are selling out to a model of old-world capitalism. In turn, they are dooming their community to a future much like the one we have today.

Alexander Weinstein is the Director of The Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing and the author of the short story collection Children of the New World (Picador, 2016). His fiction and translations have appeared in Cream City Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Notre-Dame Review, Pleiades, PRISM International, World Literature Today, and other journals. He is the recipient of a Sustainable Arts Foundation Award, and his fiction has been awarded the Lamar York, Gail Crump, Hamlin Garland, and New Millennium Prizes. He is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Siena Heights University, and leads fiction workshops in the United States and Europe.