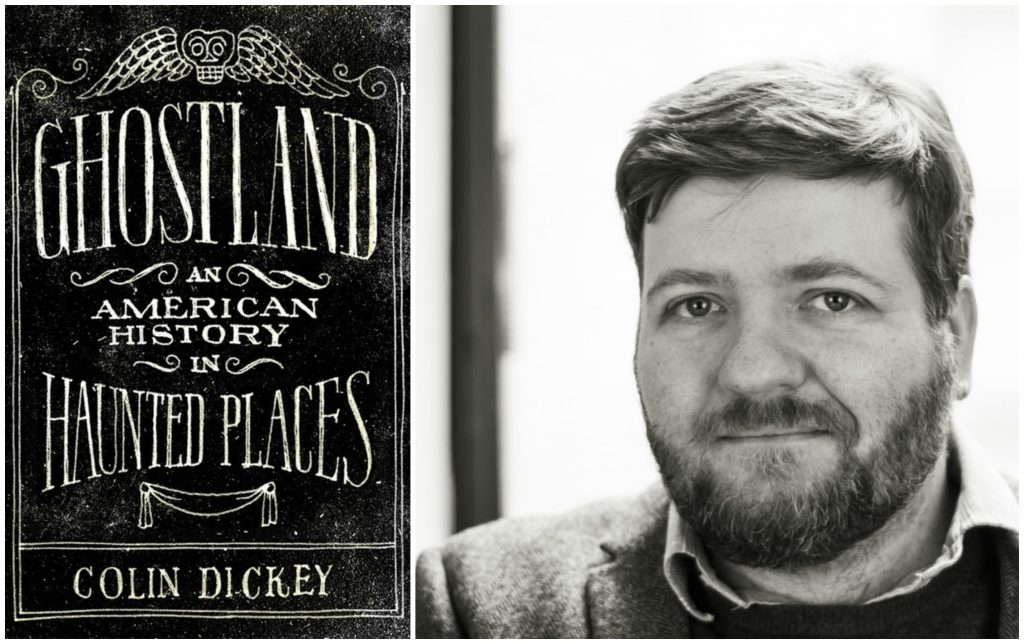

“Americans live on haunted land because we have no other choice,” writes Colin Dickey in his latest book, Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, released this month from Viking. “Like the ground beneath their property, over the years these stories have shifted with the tides and with the tastes of the tourists, changing subtly with the landscape.”

Dickey’s exploration into the ghost stories of America focuses less on their paranormal quotient, and more on what they reveal about society. The author visits a full range of haunted places, from Salem’s Nathaniel Hawthorne-immortalized House of Seven Gables to the haunted hotels of Hollywood, stopping at many an infamous haunt in between (think: Detroit’s ruined factories, Richmond’s abandoned slave markets, and many among America’s legions of historically troubled asylums, brothels, graveyards, and prisons). In each locale, Dickey dissects the sociocultural meaning of these places’ infamous ghost stories.

Ghostland is a book about the spiritualization of corporeal feelings. It’s a fascinating investigation into how those moans from the insane asylum on the hill may be less about ghosts, and more about our discomfort with the segregation of the mentally ill.  It’s about cities that have perhaps not made peace with the racial inequalities marring their pasts, but that have also found a profit stream in the ghosts they’re effectively scapegoating for said transgressions.

It’s about cities that have perhaps not made peace with the racial inequalities marring their pasts, but that have also found a profit stream in the ghosts they’re effectively scapegoating for said transgressions.

Ghost whack-a-mole, however, this book does not play. Dickey, despite his knack for finding fringe characters and exposing troubling currents of discrimination and disenfranchisement, is not out to dispel the existence of ghosts. He simply takes readers on a literary, ghost-busting road trip — hitting local libraries and newspaper archives in pursuit of the real origins of infamous ghost stories. Yet, he also rides along with paranormal investigators, and talks to spooked local citizens. No matter where he is or what he finds, the author never concludes that a place is or isn’t haunted.

Dickey, who holds a PhD in comparative literature from the University of Southern California, teaches creative writing at National University, and co-edited 2009’s The Morbid Anatomy Anthology, conjures the dead by questioning the living, and by examining the ways in which ghost stories evolve over time. His open-minded yet agnostic investigation results in a clearer, yet more nuanced understanding of what supposed paranormal activity truly means to us, and what hauntings say about our nation’s complicated history–how ghosts, essentially, have shaped our perceptions of the past, and can also help us make sense of our present.

The author, unsurprisingly, had a busy October, so I felt lucky to catch him in between spooky readings at the haunted Sarah Winchester Mystery House and Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. The cultural historian and writer generously shared insights into his writing process and inspirations, as well as his passion for offbeat history.

*

When was the moment you knew you needed to write this book?

I think it started about 2009. I’d grown up near Sarah Winchester’s Mystery House in San Jose, California, and I’d always thought it was this cool thing, and I’d recently finished my first book and was thinking about what to do next. It occurred to me that there was a cool story in Sarah Winchester’s life — no biography existed — and it slowly shifted to be about all these other stories, too.

How did you pick the other stories?

Once I’d moved on to the larger project, it became a question of Googling the most haunted hotel, the most haunted cemetery — things of that nature. What I ultimately tried to do is two things: 1) Offer regional variety, so I tried to touch on a broad swath of the country; and 2), make sure each story had something unique to contribute, so the book wouldn’t become any sort of encyclopedia or guidebook or laundry list.

I liked how you dedicated a chapter to each story, and organized the chapters into broader categories, such as “houses and mansions” and civic spaces (i.e. prisons and asylums and cemeteries and parks). Were you working with any structural models?

Once I’d found the stories I wanted to write about, it was sort of a puzzle piece situation-you’re rearranging things constantly, to figure out what’s gonna fit, what’s gonna make sense. I wanted the book to be loosely chronological — it starts with colonial Salem and ends with the housing crisis of 2009 — and at the same time, to organize outward, from small spaces like the home, to larger spaces like restaurants and prisons and hospitals. The idea, I guess, was to provide a structure that could keep furthering the conversation — keep it going somewhere and sounding new.

Each of these stories here seem to have involved a lot of sleuthing — into cultural, popular, and literary history. Tell me about your research process.

Each chapter had its own process, because the subject matter was so nebulous. There’s so much crap out there on the Internet about everything. So, you start with that crap and then you fact check where you can, and often there’s a limit to what you can do, so you end up talking to folklorists and local historians, and tooling around these places yourself. The process was completely different for each chapter — in some cases I paid college students to research newspaper archives.

You’re a teacher and a freelance writer. How did you manage to pull off all these research trips?

I made all these short and sporadic trips here and there, and longer trips when I was available, and drag my wife or anyone who was free along with me. The locations sometimes shifted unexpectedly, or I’d decide I didn’t need to go to a certain place — the travel schedule was sort of about whatever I could get away with [laughs].

What surprised or shocked you the most?

So many things [laughs]! I was surprised by the variety of stories, and the differences I found regionally, and then doubly surprised by some core innate similarities that managed to come up time and time again. You’d find certain archetypes that would appear no matter what. For instance, the haunted merchant’s house in New York plays off the mythology of the unmarried woman, the spinster, as does the Winchester House. Things like this would crop up unexpectedly across the country, despite their radically different places and stories and cultures.

Did any particular story scare you or make you feel vulnerable to the spirit world?

I certainly felt the most disturbed at the West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville. Maybe less from any fear of the paranormal and more of a sense of, This is a building that was meant to unsettle and unnerve its inhabitants. It’s architecturally designed to be an unpleasant and scary place to be, and all that was compounded by years of overcrowding and mistreatment and mismanagement. It’s hard to be in a place like that and not feel its effects on you.

You are a member of the Order of the Good Death, a collective of artists, academics, and death industry professionals interested in promoting a more “death positive” attitude in the Western world. How did that influence your relationship to these stories?

The Order was started by Caitlin Doughty, a practicing mortician and writer who has really helped drive this conversation about how we talk about death, dying, and funeral customs — it’s about opening up that conversation and destigmatizing it. I’d always been drawn to those questions, even before I knew Caitlin. For me, this focus on ghosts and spiritualism and the afterlife are all related to how we talk about death and our loved ones. It’s an attempt to take that seriously, to further that discussion.

Who are some nonfiction writers and/or cultural historians who inspire you?

Too many to list! I certainly spent a lot of time reading and thinking about Erik Larson’s work. Same with Simon Winchester. I’m also influenced and inspired by a lot of writers whose work on the surface has nothing to do with what I’m doing, like Eula Biss and Maggie Nelson.

Your tour of haunted America seems to reveal that the meaning of ghost stories is generally rooted not in the occult, but rather in what they inadvertently say about the anxieties and prejudices of their teller, and of society. Have you experienced any backlash from the ghost-hunting community?

So far, not yet [laughs]. We’ll see, but again, I feel like there are some people in that community who get involved for less than noble means, in it for the money. But I feel like overall, people treat this as a spiritual endeavor, as a way of getting in touch with something larger than themselves. And I think that’s heartwarming, and a respectful reason to be in the trade.

Is there a favorite ghost story in your book?

As David Byrne once said about his songs, they’re like your children; you love them all differently.

How are you going to celebrate Halloween?

The tradition of telling ghost stories used to be associated not with Halloween, but with Christmas. My wife and I, for the past few years, have hosted a gathering where people show up and tell all sorts of random stories they’ve heard. So I’m kinda more excited about telling Christmas ghost stories.

What’s next for you, writing-wise?

It’s up in the air, but I’ll probably continue to seek out the kind of history that’s often treated as marginal or uninteresting, and seeing if I can pull larger themes out of it.

*

Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places is available through Penguin Random House and Amazon. Find out more about Dickey’s upcoming projects at colindickey.com, or follow him on Twitter @colindickey.