One in eight couples has trouble conceiving — as do cicadas, gorillas, and other members of the animal kingdom. A complicated and often ambiguous condition, infertility arises from a number of factors, affects both sexes in equal measure, and, despite how common it is, historically tends to result in shame, silence, and/or social isolation.

For several years, Belle Boggs — a North Carolina State University professor and the author of 2010’s award-winning story collection, Mattaponi Queen — struggled to have a child with her husband. The experience exposed her to the plight of many others, via an infertility support group, as well as through online message boards where aspiring parents recounted the triumphs and travails of their (often repeated) IVF experiences, down to the number of embryos (“embies”) produced in each cycle. Despite the condition’s rampant disappointment and failure, giving up, for Boggs and for the fellow infertility sufferers she comes to know, is difficult. There’s always another treatment or technology to try. There’s also adoption, and ever more payment plans to pursue while the debt accrues — more time to spend waiting.

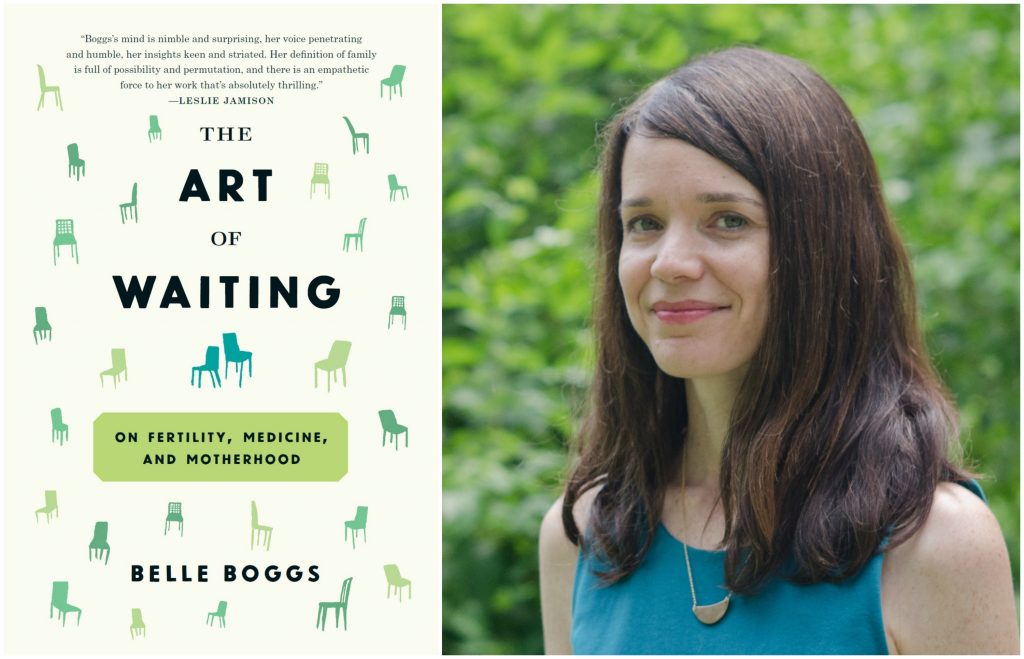

Thanks to IVF, Boggs and her husband eventually gave birth to a healthy daughter. But not before she began documenting her intense desire to have a child, and dissecting the barriers — physical, financial, and emotional — standing in the way. An artful, direct exploration of the many ways one can choose to make a life, and what it means to make a family, the twelve distinct essays comprising Boggs’s resulting collection, The Art of Waiting: On Fertility, Medicine, and Motherhood (Graywolf Press, September 2016), function as a curious and empathetic meditation on childlessness, childbearing, and the agony that, for many, stretches in between.

The Art of Waiting also examines the emotional complexities of adoption, and the (typically unhappy) fates of childless characters in literature. Perhaps most compellingly, it confronts a range of contemporary social issues. While we often think of infertility as a white, upper-middle-class problem, for instance, Boggs’s writing clarifies that it is in fact a condition that disproportionately affects minorities, the poor, and the less educated. The Art of Waiting also delves into the experiences of those left out of classic narratives of conception — hopeful LGBT parents, those who conceive via assisted reproduction (egg and sperm donation) and/or with surrogates, those who choose to adopt, and well as victims of eugenics programs — humans who were sterilized against their will.

Boggs’s efforts may have paid off, but her years of waiting gave her the empathy to write compellingly about cultural narratives of fertility, as well as the medical, emotional, and financial experience of its inverse. In a recent conversation, she generously detailed another complicated experience: the process of capturing all this complexity in writing.

*

Tell me about the moment you knew you needed to write this collection.

It’s a little hard to pinpoint, as I worked on individual essays before deciding to try to write a cohesive book. But maybe it was when I interviewed Dr. Silvia Ramos, the embryologist who at the end of an interview about her work shared with me her story of motherhood — her youth presented its own set of challenges — before telling me “now is your time.” I saw then that my story could help me connect with others — even women whose lives looked much different than mine — and also that my research could help me decide my own path to motherhood.

Or it may have been months later, when I was ordering medication for my first round of IVF with a well-drilling rig boring a deep, expensive hole into my property. I began writing about that experience as it happened. The parallels between drilling for water, when you don’t know if you’ll find it or just spend all your money trying, and IVF, were so striking, and I saw that — for a time at least — a lot of my life would be filtered through this lens of waiting and mystery.

Were you working with any structural models? Did any other essay collections guide you?

I thought for a while that I would structure the book in a seasonal way, like Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. I love that book and have always written about landscape and home, but as I began researching The Art of Waiting I saw that I would have to be looser, more flexible, to accommodate the stories of other people — adoptive families, other infertile couples who chose assisted reproductive technology, gay couples facing discrimination in ART or adoption. I still think there is seasonality to my story — I begin and end the book with descriptions of springtime cicada broods in different years, and mark time with the birth stories of a gorilla troop at our NC Zoo — but that’s not a strictly-regulating feature.

Graywolf Press has been a big influence on my writing. I love so many of their collections and nonfiction works — Eula Biss’s Notes from No Man’s Land and On Immunity, Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams, Kim Dana Kupperman’s I Just Lately Started Buying Wings, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts — for the way those writers are able to address their personal histories while also ranging widely into other territory: research, cultural commentary, reporting. Another independent-press book I thought about a lot was Milkweed’s Ecology of a Cracker Childhood by Janisse Ray, which does such a beautiful job of balancing personal history with science and nature. And other nonfiction books inspired me too: Andrew Solomon’s The Noonday Demon and Far from the Tree, so deeply researched and full of wisdom, Sarah Hrdy’s fascinating writing about motherhood and the maternal instinct in Mothers and Others and Mother Nature, both recommendations of a biologist friend.

Tell me about the process of ordering these essays. How did you decide what would go where?

I think they fell into place pretty naturally — I’d written a detailed outline to help guide me, and Katie Dublinski (my editor) and I talked frequently about how to order the essays, how to avoid repetition while also keeping the reader grounded in the collection’s narrative through-lines. Part of the collection follows my story, of ambivalence about treatment and searching and deciding how to respond to the diagnosis and experience of infertility. Interspersed are the stories of other people, and the choices and sacrifices they made on their paths.

Tell me about the audience you had in mind while writing this book.

My first audience was my husband, then after that I thought about the women I knew in my support group, the mostly private pain we talked about each month around a table in the basement of a hospital. I was so grateful to them for the time we spent talking and listening, and I wanted to pay tribute to them, to the long and uncertain waiting they faced, the emotional and physical and financial struggle of infertile couples and individuals.

I also wanted to find out how stereotyping and bias and the high cost of IVF affected access to treatment. Doctors don’t always know the risk factors for infertility, and poor women, or women who don’t look like the infertility patient we recognize from movies and literature and advertising, sometimes have a hard time even getting referred to reproductive endocrinologists. Healthcare access has been interesting and troubling to me ever since I was a child — my brother had severe asthma as a kid, and I remember that my parents always had to fight with insurance companies, with hospital billing departments. I grew up in a very rural area, and access to so much was limited.

But I hope that the book can also be read for the writing, which is the other reason I have started to work in nonfiction. I want to learn something through my research and express that in a clear and accessible way, but I also want the writing itself to feel fresh and unexpected.

How does your nonfiction writing process differ from your fiction process?

I am always telling my nonfiction students to get out into the world, into interviews and experiences they can bring back to their writing. That’s one of the great benefits of this kind of work — sitting down with the voices of other people, the details from our fieldwork and research. You become a kind of arranger/composer, someone who is also committed to telling the stories of others, which has a useful urgency.

Your book is so chock-full of literary references, as well as insights into healthcare, and the socioeconomic factors surrounding infertility. Tell me about your research process. How did you balance it with the writing?

This is one of the things I love about writing nonfiction — it feels like you are less alone, and the whole process of writing this book was one of searching for community. I found it in books, from Tillie Olsen’s Silences to Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born, in interviews with women and men who’d approached the complex worlds of what legal scholar Martha Ertman calls “Plan B” family-building, and in the fascinating research of biologists and sociologists. Research feeds my writing; it makes me feel less alone as a person and less alone as I sit at my desk, trying to figure out what to say and how to say it.

But in my nonfiction classes we also talk about storytelling and the importance of language, and the way that the same pressures and techniques we use in fiction and poetry apply to nonfiction writing.

Do you have a favorite essay in the collection?

I really liked writing “Baby Fever,” which is about the movie Raising Arizona, and includes some fascinating qualitative research into the sometimes punishing phenomenon of baby fever, or child-longing. I loved doing all of the research that went into the gorillas’ infant-stealing stories, which appeared originally in the “Baby Fever” essay that was printed in Orion. I can tell you I did not want to write “Carrying” — an essay about my daughter’s birth — partly because I worried that it would be alienating to some readers. But [Graywolf publisher] Fiona McCrae pushed me to do it, and I found writing it was useful and even cathartic. But I’m not sure I have a favorite.

Can you name a couple of your favorites essayists or essay collections?

I keep reading and rereading Natalia Ginzburg’s The Little Virtues, a book I wrote about recently for The New Yorker’s “Page-Turner” section. This year I was also really impressed by Brian Blanchfield’s exquisite Proxies, and I’ve enjoyed teaching essays from that book to my students. I have read Citizen many times now. And of course Joan Didion — I write about her descriptions of child-longing and adoption in the book.

Have you come up against any backlash from these essays’ publication?

Only minimally, from people who have assumed a particular agenda from the book’s stories: for or against adoption or surrogacy or IVF. Some people take issue with calling infertility a disease, but I think that’s the only way we can advocate for better awareness and insurance coverage, so that people have choices. And my point was not to say that one path is better than another, but to portray the experience of exclusion and isolation, and the obstacles faced by so many people, with empathy.

What are you reading right now?

I just finished Pamela Erens’s Eleven Hours, which I loved. I’m also reading Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Sayings, Joy Williams’s Ninety-Nine Stories of God, and Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad — all terrific. I also have a copy of J. Drew Lanham’s book on birding and nature and family history, The Home Place, waiting for me on my shelf. And I’m very excited for Mike Scalise’s memoir, The Brand New Catastrophe — I just got the ARC for that long-awaited book, which comes out from Sarabande in January.

What’s next for you, writing-wise?

I’m working on a novel for Graywolf Press called The Ugly Bear List. It’s set in the worlds of for-profit education and inspirational/Christian writing — I can’t wait to get back to it.

And now for a quick lighting round! When writing, do you prefer…

-coffee or tea?

Coffee!

-morning or night?

Morning (with coffee)

-silence or music?

Birdsong and nature sounds

-to write longhand or type?

Typing

-the company of dogs or cats?

Cats, or maybe an old dog that likes napping.

*

The Art of Waiting is available through Graywolf Press and Amazon. Find out more about Boggs’s work at belleboggs.com, or follow her on Twitter @BelleBoggs.