I’ve been thinking a lot about diaphragms and the endurance of classics. Stay with me here.

For the first paper in the composition course I teach, my students are required to perform a close reading of T.C. Boyle’s short story “Caviar.” The story follows Nathaniel, an insecure fisherman whose class anxieties force him (or so he vehemently claims!) to cheat on his wife with the surrogate mother of his child. Early on in the narrative, when Nathaniel and his wife, Marie, are considering starting a family, Marie makes a powerful declaration of her intentions to procreate by burying her diaphragm in the yard. It’s one of my favorite moments in the story: one of those gestures that, even early on, feels so divorced from Marie’s character that we are able to see her clearly in the contrast we perceive.

One of my students, however, pointed to the passage for an entirely different reason in our discussion earlier this month. “This isn’t about close reading,” he began, “but I have a question about the story.” After I urged him on with a nod, he asked, “how’d she take out her diaphragm?”

Not wanting the discussion to completely devolve into a sex ed class, I hoped to veer away from having to explain anything by just asking more questions back. I also hoped I’d maybe just misheard the question. “What do you mean?”

“I mean…” He looked visibly uncomfortable. “Did she take her diaphragm out of her … is this supposed to be like the diaphragm like the muscle? I don’t know if I read this correctly.” This was followed by several mutters of agreement from around the classroom.

I realized then that my class had no idea what a diaphragm was. I explained, as carefully and minimally as I could in an effort to eventually return to our planned discussion, what a diaphragm was within the context of the story. But the full effect of the scene was still lost on them. “So, it’s like throwing her condoms away?” one asked.

“Well, kind of,” I conceded. “Except it’s more than that. You don’t just get a diaphragm at the drug store. Back then, you’d go and get it fitted by a doctor or at a women’s health provider. So it’s almost like throwing away an IUD–it took her effort to get it and she can’t just run out and quickly grab another if she’s changed her mind.”

“Oh!” The original student exclaimed. “So did she just pull it out of herself and then … ”

“She’s not always wearing it.”

There was a notion repeated entirely too often in many of the workshops I’ve attended that work loses its ability to be timeless the moment we braid in modern innovation. Often, this pertained to the use of texting, mentions of the Internet or social media, and references to prominent media figures. I’ve encountered writers who seem to deny the existence of the cell phone in their stories, despite their solid ubiquity for nearly two decades.

The fear, I suppose, is setting a story too firmly within its time. The effect, however, is sometimes something along the lines of Burlesque, that movie with Cher and Christina Aguilera where they eat Famous Amos cookies but nobody owns a phone. It’s impossible to drain all cultural markers from a story, no matter how dedicated we are to the idea of making something universally relatable or timeless, and the litmus for what we consider to be ephemera feels arbitrary at best.

I’m reminded of another important diaphragm in literature: Brenda Patimkin’s in Philip Roth’s novella Goodbye, Columbus. Again, the diaphragm serves as a vehicle: we see Brenda’s reluctance in “going to Margaret Sanger” to procure it, and we watch her and Neil’s relationship blossom and eventually crumble around it. After all, the Patimkins’ discovery of their daughter’s diaphragm in her nightstand serves as both the climax of the story and the means of destruction of Neil and Brenda’s love. And even as readers may fail to comprehend that “going to Margaret Sanger” has evolved into going to Planned Parenthood, or the courage of an unmarried woman in the 1950s going into the city to acquire birth control, Goodbye, Columbus remains accessible. Neil, dizzy with longing so fraught that it often crosses into rage and frustration, touches upon the sort of fumbling, naive, bitter machinations of first love that scan whether expressed via carrier pigeon or in text message. And Brenda’s shame over her burgeoning sexuality is something that unfortunately remains all-too-familiar almost sixty years later.

The cultural markers — or lack thereof — in a story are not what makes a piece of writing timeless. We do not transcend time by simply disregarding its march. Even as the diaphragm loses its prevalence and potency, the stories that incorporate it do not because literature was never intended to be generic, was never meant to either speak for one time solely or no time at all. Moreover, to base endurance on the ability to write in the absence of cultural markers dismisses the very reason for which one could argue we read at all: to see ourselves in the otherwise unfamiliar. Don’t tell me that the human heart cannot make those sorts of leaps without stumbling over a diaphragm or a text message.

*

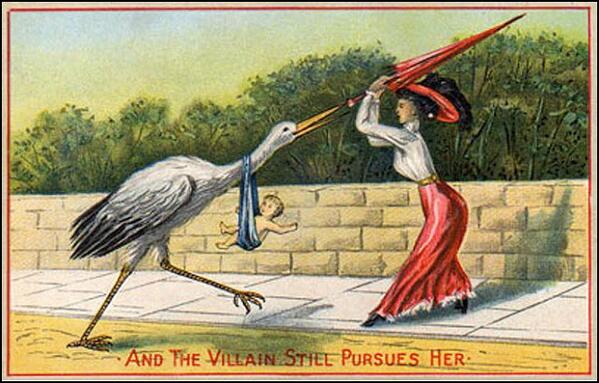

Image: “And the villain still pursues her.” Victorian-era postcard.