In 1994, South African anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela, newly released from a life prison sentence, negotiated an end to his country’s centuries-long system of institutionalized racism, organized its first fully representative democratic election, and became South Africa’s first black chief executive. Shortly before apartheid’s twilight, however, on August 25, 1993, a young American Fulbright Scholar — an idealistic, brilliant, blonde Stanford graduate — was murdered, ostensibly because of her white skin, at the hands of a mob.

Amy Biehl died in a Cape Town township; i.e., an undeveloped patch of urban South Africa. Afterward, four township men were found guilty of her murder and locked away in prison. In 1998, however, they were released as a result of Mandela’s celebrated Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a restorative justice initiative intended to grant amnesty to the perpetrators of political crimes committed during apartheid.

Based on the understanding that their daughter’s murderers had been operating under the One Settler, One Bullet! rallying cry of the Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania — the liberation movement to which the men belonged — Amy Biehl’s Californian parents not only pardoned them, but publicly embraced them. They even famously employed two of them in the charity foundation they established in their daughter’s name. This act of grand reconciliation came to symbolize what Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu were striving to achieve in the new South Africa which they dubbed, “the rainbow nation.”

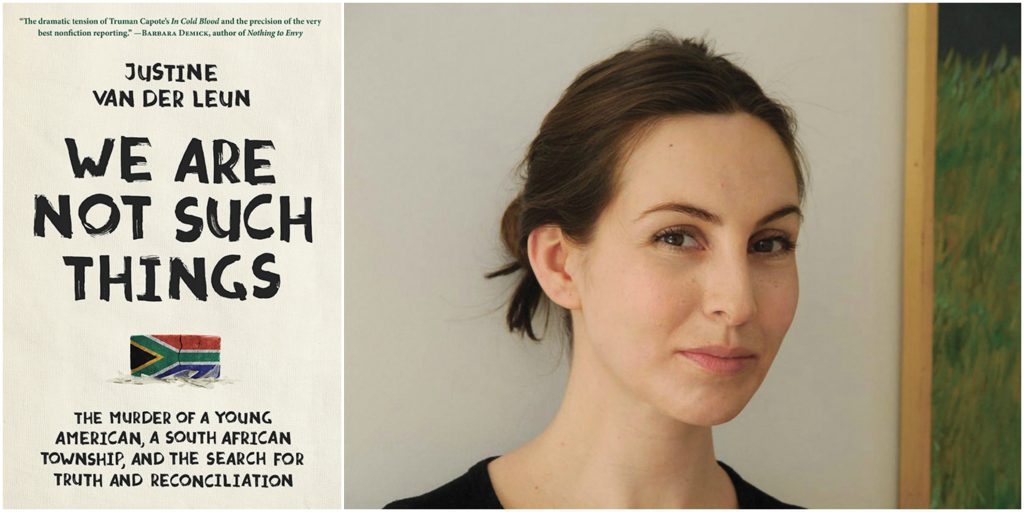

The story of Amy Biehl is well known in South Africa. Two decades ago, the Biehls’ darkly feel-good story was all over the U.S. news, too. It was also the subject of multiple documentaries, but never, as the young American writer Justine van der Leun discovered when she moved to the country with her South African fiancé in 2011, of a full-length book. Believing she’d landed on her next project, van der Leun immersed herself in the lives of the key players in Amy’s story — her mother, Linda (her father Peter had passed), the two killers the Biehls had come to love practically as their own sons, and several residents of the township in which she died.

As van der Leun, a freelance writer and the author of the travel memoir Marcus of Umbria (Rodale Books, 2011), delved into the case — combing court transcripts and contacting not only key witnesses but their friends and far-flung associates — the prevailing narrative of Amy Biehl’s death started to unravel. For one, eyewitnesses couldn’t agree on who had actually killed Biehl, or what exactly had motivated that day’s mob mayhem — was it actual political revolt, or just sad, senseless circumstance?

In the course of van der Leun’s four-year investigation into that question, it became unclear whether the convicted men were, in fact, responsible for Amy Biehl’s death (because they had been benefiting from their subsequent reconciliation with the well-heeled Biehls, however, there was little motivation for them to cop to any innocence or misunderstanding). What’s more, van der Leun ultimately stumbles upon evidence that a similarly brutal and racially-motivated — albeit almost entirely un-publicized — crime had been committed on the same day, in the same area of the township. Such a discovery only serves to inflate her investigation into a full-fledged, true-crime undertaking.

The true story of Biehl’s death, as van der Leun reports in We Are Not Such Things (a title borrowed from one convicted murderer’s pained response to a prosecutor’s portrayal of him and his co-defendants as cold-blooded killers), is not only ambiguous and murky, but also emblematic of the complicated history of a country long besieged by injustice and violence. Ultimately, van der Leun’s book does not provide a clear picture of what happened on August 25, 1993, but rather, makes a powerful case for why it would be impossible for any medium to do so. It also paints a vivid and nuanced portrait of South Africa’s confounding, convoluted past and present. Above all, We Are Not Such Things functions as a probing commentary on the unreliable nature of accepted narratives — the ways in which their ceaseless retelling can solidify such stories into myths, can warp the memories of even their most primary tellers.

Putting such thought-provoking, perspective-widening bona fides aside for a moment, We Are Not Such Things also offers an engrossing, transporting story, one populated by extraordinary characters. The author is candid about her own privilege relative to her subjects, as well as her naiveté where investigative journalism is concerned, and the result is a refreshingly transparent, energizing mission to uncover the truth — or whatever version of the truth may be accessible. As I discovered once I had the pleasure of speaking with van der Leun over the phone, the author is more than generous, too, when it comes to revealing her project’s inspirations, methodology, and personal takeaway.

Tell me about the moment you realized what a massive, investigative project you’d undertaken.

Initially, I was going to tell the story of Amy and her murder, the subsequent criminal trial, the [Truth and Reconciliation] Commission, and her parents’ amazing feat of forgiveness. It’s a story that’s pretty well known in South Africa, and one that was at one point quite well known in America. I was on the way to telling that story when I got in touch with Mzi Noji, who had been very involved in the same political group as the convicted murderers, the Pan Africanist Congress [PAC].  Mzi had never been asked anything, but was still part of the PAC — which is fairly defunct and now has maybe even less than half of one percent of the vote — so when I called up their offices, asking if anyone had been there when Amy was murdered, Mzi called me back the next day. So I set up a meeting with him, expecting him to just recite the same story, but then as we were talking, he said, “You know what, that’s not exactly true.” And I said, “Are you sure?” and he said, “I know that’s the accepted narrative, but that’s not exactly what happened.” That’s when everything unraveled and I started chasing various threads.

Mzi had never been asked anything, but was still part of the PAC — which is fairly defunct and now has maybe even less than half of one percent of the vote — so when I called up their offices, asking if anyone had been there when Amy was murdered, Mzi called me back the next day. So I set up a meeting with him, expecting him to just recite the same story, but then as we were talking, he said, “You know what, that’s not exactly true.” And I said, “Are you sure?” and he said, “I know that’s the accepted narrative, but that’s not exactly what happened.” That’s when everything unraveled and I started chasing various threads.

Once you realized the story was a lot more complicated than what you’d set out to tell, what made you persevere?

After that conversation with Mzi, I could’ve kept researching [the events surrounding Amy Biehl’s murder] and talking to people for another ten years. After it happened, everyone who’d ever covered the story talked to the same people, and the people in the township by and large knew the story was more complicated than the story that was made public, but they weren’t being asked — they never had been. They also weren’t scouring the news. So once I started asking around the township about the “new developments” I’d learned about from Mzi, the majority were not surprised. So, it wasn’t that it was this secret, it was just that no one had ever gone asking these people.

Did you seek models in any other true-crime books or works of investigative journalism?

My favorite narrative investigation is Adrian Nicole Leblanc’s Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble, and Coming of Age in the Bronx. She spent more than ten years embedding herself with a family in the Bronx, and I think it’s basically been described as a book about what it’s like to be poor in America. It’s one of the books that guided me a lot. I also love Tracy Kidder’s books, and of course anyone who’s doing true crime and narrative nonfiction loves In Cold Blood. And Anne Fadiman’s The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down is a fantastic portrayal of two sides of a complicated story — it’s about the Hmong community, and this child who’s epileptic, and the clash of cultures within the medical community in America. It’s amazing; she has such empathy for both sides — believers in Eastern and Western medicine — and shows how they’re both trying to do their best for the child.

The book provides a comprehensive overview of South African history, specifically as it pertains to the country’s fraught race relations. Going into this project, how much did you already know about South African history and politics?

I’m not a historian in any way but the story of Amy was impossible to tell without the contextualization. I knew that her murder happened at the end of a long arc of a history that started when the Dutch touched down on the Cape. So I got a guest pass to the University of Cape Town and used their library to read an enormous amount about history. It was a way for me to understand Amy, and it was important for me to know how that history had led to her being there, and to them taking her down. To me, the story was the important part, but the history was necessary background.

How did you balance such an intensive research process with the matter of actually writing this lengthy, in-depth book?

I wish I had toggled back and forth more than I had! In the beginning, I thought, “Well, I’ll do the research, and then I’ll write it,” but I mean I took copious handwritten notes all throughout, and everything was recorded, too. I considered outsourcing the transcribing to a firm, but didn’t know how they’d understand South African-accented English, so I did it all myself. All told, I spent a few years doing research — 2011-2013 full time, and then months here and there until 2015 — and about a year writing the first draft.

I love how transparent you as the narrator were throughout this research process — how the reader got a real sense of who you were and why you were curious about Amy Biehl’s murder. We didn’t, however, get too much in the way of autobiographical information about you. How did you decide how much of yourself to reveal on the page?

That was, to me, the most delicate part of the process, because I really love works like Leblanc’s and Kidder’s and Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers, where, for the most part, the author is totally out of the picture — just sometimes, perhaps, making small appearances. To me, it seems like the old-school reporting style — where you, the author, do not exist — and I think when you write for certain magazines, or if you’re a real hardcore reporter, you learn to work that way. But, I am not a reporter — I think of myself more as a writer than as a journalist, so for me, it wouldn’t have been natural to take myself out. While I think the alternative is a totally valid way of working, to me it wasn’t the most honest way — I mean, I was there, I affected things. The way I got my information, which didn’t involve sort of sinking into the background, was a key part of the unraveling of the story.

Who was your target audience? As you were writing, how did you envision your reader?

When I write I don’t think of the reader. I don’t think of anything except the story, maybe because it’s too daunting to think about being judged, and I feel like I just have to clear my mind and write the story that I have to write. As a writer, you’re already questioning too much.

What were you hoping the takeaway would be for someone like, say, myself — a youngish American reader who’s never set foot in South Africa?

I think it’s great that people will incidentally learn about South Africa, and probably draw some comparisons between the legacy of apartheid and the legacy of slavery — how history creates the present. But as I mentioned, I’m not that interested in history for its own sake, or politics for its own sake. I’m into how the history and the politics affected the people. I guess the biggest takeaway for me was having this idea of the other; for instance, Easy [one of Amy Biehl’s forgiven murderers], a poor black man raised during the struggle, and Mzi, an ex-military nationalist living in a shack. I felt so separate from these people until I started doing the book and found this common humanity, and I think it goes back to the title [We Are Not Such Things], the idea that people are not these caricatures you have in mind. If you’re open to learning who they are, you’ll be astounded to see how many multitudes they all contain. And of course, I hope another piece of takeaway is that there are no clear-cut judgements or answers, so always be wary of the common narrative that you hear.

We Are Not Such Things: The Murder of a Yong American, A South African Township, And the Search for Truth and Reconciliation is available through Penguin Random House and Amazon.

Author photo via startribune.com.