When I was seventeen, I first read the short story that made me want to become a writer. Before it, my reading had been restricted mostly to novels that were recommended by my local librarian and books that were assigned in school. Though I would have called myself a voracious reader, my experience with short stories was scant, if any.

The short story–and the collection that contained it–was recommended to me by a mentor who must have seen some potential in what I was writing for school, who claimed that this was one of his very favorites. Even going in with these high expectations, I was still blown away. I had never before seen the way a short story could contain a burgeoning world. The way it could align you with an individual or make you trust a narrator in less than a few paragraphs. The way it escalated all at once, a column of flame, before abruptly snubbing itself out. I became addicted to the way a short story could leave you in its wake: the gut-punch, the breathlessness.

I credit this story collection with not only the decision to take a creative writing class in college, but also with the stylistic choices I made for the stories I handed in. If the novel was capacious and consumed with itself, the short story was curt and over itself. The novel wanted to connect you to your humanity, the short story made you ashamed of it. I went through class after class writing stories ruled by jealousy, bitterness, resentment, regret, carried by narrators who were entirely too aware of their situations or foolishly unaware or simply too frustrated to do anything about it. That collection served as my holy text, my standard. I even mapped its stories and tried to see if my own fit along the arc.

The last time I read the collection was probably around the time I was nineteen. Afterwards, I expanded my repertoire. Stuart Dybek’s “Pet Milk” taught me the malleability of narrative. Kelly Link’s “Stone Animals” taught me that even the most alienating story could still evoke the familiar, as did the stories in Haruki Murakami’s “The Elephant Vanishes.” Rebecca Makkai’s “The November Story” gave me permission to write about television, giving the genre its due dignity while still acknowledging its limitations. Colum McCann’s “A Fear of Love” turned the “meet cute” on its head and taught me how to write a nuanced love story: a genre of short story I had avoided for fear of turning up cliche after cliche. As I grew as a writer, the list of short stories that I would call formative grew, as well.

But when, in the first year of my MFA program, a friend asked to borrow a book I considered formative or important, I picked the original collection. I had not picked it up in three years, but I had no doubts that it would touch her the way it touched me. But when she returned it, she seemed reluctant to give a review. After some prodding, she relented.

“It was interesting, but, well.” She hesitated for a moment. “Well, they’re all the same story. And most of them are pretty much bro-fiction. You know?”

I didn’t know. Too frightened to read it back and ruin it, I lent it to another friend. Same reviews. With a lump in my throat, I read the entire collection in one agonizing night. They had been right: they were all the same story. And a lot of them were super sexist. Incredibly sexist. Sometimes embarrassingly so. I was unsure where I had even found a space for myself in these stories in the first place. Especially when the collection seemed to insist upon the fact that girls between the ages of seventeen and thirty-five were both perfect and the root of all evil. That didn’t leave a lot of options.

It’s hard to honor the things that once inspired you, just as it feels equally difficult to say that you’re somehow “beyond” them. It feels ridiculous and condescending to say I’ve outgrown a collection of short stories, especially when that collection gave me a gift and an obsession.

So how do we honor the books we no longer identify with that once felt like the perfect articulation of our being? My strategy for the longest time has been to simply not reread them. But that sort of willful ignorance just doesn’t feel sustainable. There has to be a way to honor what the book once did while still problematizing its contents. (Or I could just avoid things like Atlas Shrugged and Charles Bukowski forever.)

When I was a child, I lived in a town in which almost everything was within walking distance from my home. Thus, whenever we went on a car trip, my young mind processed it like I was crossing into another country. The half-hour drive to my great-grandmother’s house could easily feel like three hours. I feel foolish now considering how I’d totally overblown the trip to some kind of epic voyage that my father and I took every Sunday. But looking back to the singing along to Foreigner (another thing that unfortunately just does not hold up to its original glory) and air-guitaring with my dad at stoplights, perhaps it is okay to revere what something gave you while still minimizing how grand that thing actually was.

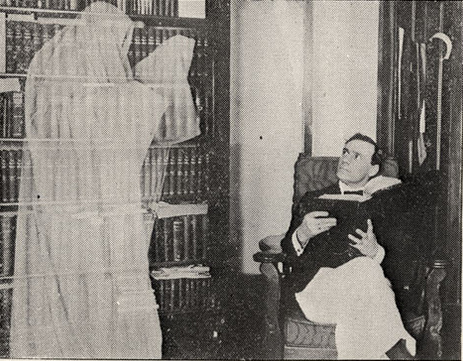

Image from “Trick Photography,” by Walter S. Eagleson, 1902.