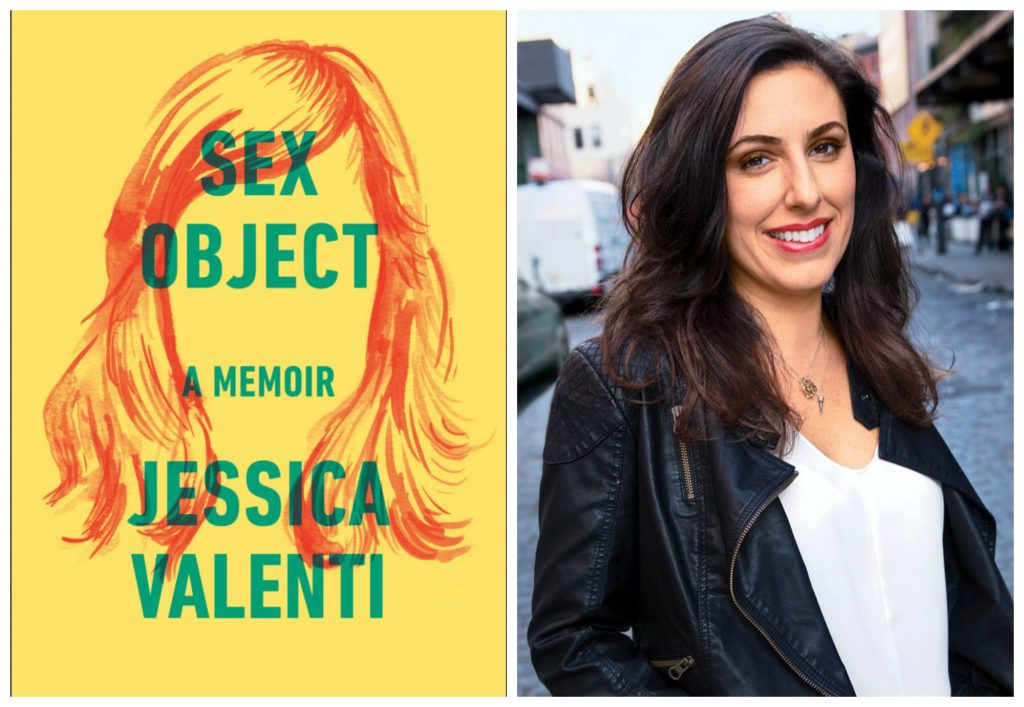

Jessica Valenti wants to know what it would be like to live in a world that doesn’t “hate women”—what it would have been like to be raised and have come of age in a culture that didn’t subject half its population to forms of harassment, sexism, and sexual assault so commonplace as to be perceived as normal. Such is the probing, narrative force of her first memoir: the ultra-candid, darkly funny, and often disturbing Sex Object (Dey Street Books, June 2016).

Valenti, the 2004 founder of Feministing—a popular website intended to engage younger women in feminist discourse—is often credited as a pioneer in bringing the feminist movement online, where it’s gained considerable visibility and traction. As the author or co-author of four books that explore women’s issues, including Full Frontal Feminism (2007) and The Purity Myth (2009), and as a frequent contributor to Guardian US, The Atlantic, Washington Post, and The Nation, Valenti is considered a leading feminist of her generation. In Sex Object, however, she veers away from political issues and overt cultural analysis—sweeping readers along through her childhood in Queens and her young adulthood in New York City, and into her experiences as a mother and celebrated feminist writer—to explore the very real toll that garden-variety sexism takes on the psyche. “Recognizing suffering,” she writes in the first chapter, “is not giving up, and it’s not weak.”

Those unfamiliar with Valenti’s more typical fare may be shocked (and enthralled) by her candor in Sex Object. In a non-chronological fashion that blends memoir and ever-so-subtle feminist analysis, the author reveals her own sexual experiences (both good and bad), and also writes about dealing with harassment, taking drugs, having abortions, fielding the come-ons of a married male friend, and a harrowing episode that saw her nearly die during childbirth. She also details the travails of her own motherhood and marriage, and explores the abuse suffered by her mother and grandmother before her.

Valenti artfully and often humorously captures a culture that values women based on whether or not they’re sexy, but that also, as she puts it, “hates them for having sex.” While she and many other writers have previously addressed said double standard, Sex Object doesn’t seek to offer solutions, nor to make broad political statements. It’s simply a documentation of the everyday experience of living in a world that doesn’t necessarily see women as “full people,” but that rather forces many into an alternate, sub-human identity—that of being a sex object. What further sets Sex Object apart is its exploration of sexism within a particularly modern nexus of everyday life—the Internet. A daily recipient of misogynistic vitriol, Valenti raises important questions about the long-term effects of hate speech and online trolling, largely by ending Sex Object with a verbatim and often chilling transcript of some such messages she’s received via social media and her own website.

The result is an engrossing, provocative, and remarkably un-didactic read that makes a powerful case for why we need feminism—and why it may be particularly crucial in this digital age. I finished the book in two absorbing sittings, and was delighted to have the opportunity to speak with Valenti about the power women wield when they share their own stories.

*

Tell me about the moment you knew you needed to write this memoir.

It wasn’t really a decision so much as something that just happened. I had started to write this food column over at The Toast, Eat Me, that ended up being much more about my family and my young life than I expected. I enjoyed writing like that so much—it became a particularly cathartic form for me—and got such an amazing response, that before I knew it, I was just writing like that on my own. So it wasn’t like, “Oh, I should write this book;” it was more like, “Oh, well I already wrote half of this book.”

In what ways do you see memoir as a vehicle for social change?

I write about feminist theory so explicitly all the time that it didn’t feel necessary in this book. I just wanted the stories to stand on their own. Right now, we’re in this moment where women are telling their stories, where first-person narrative is big, where people are really using their experiences to contextualize political issues. And I don’t just mean in books and articles, but even on Twitter, where thousands are using the hashtag #yesallwomen.

You’ve mentioned that you’re fascinated by the huge backlash we see when women tell their own stories.

It’s really fascinating. For a long time, there’s been this notion that men’s memoirs are conveying universal experiences, whereas women’s stories are self-indulgent, salacious—just too much. You see it in reviews—if a woman writes about sex in any way, she’s looking for attention, whereas someone like Philip Roth is brave and amazing. That’s really coming to a head right now, so it’s been an interesting time to do this sort of writing and this sort of work. Which makes it exciting but also terrifying, because you’re basically girding yourself for what you know is going to be an inevitable response. The book’s not even out, but people on social media are taking screenshots of the cover and being like, “Jessica Valenti thinks she’s a sexy sex object?! Who is she?,” and I knew that was coming.

Do you think all this online abuse that many receive—especially women and feminists—will come to a head? What can be done about it?

I wrote my first article about this in 2006. So we’ve been talking about it for at least ten years, but it seems like just right now, people are realizing it’s a serious issue. It’s often seen as a bit of an If you can’t stand the heat get out of the kitchen! situation, but the thing is, this is something online platforms can do something about. For instance, YouTube has an algorithm, a function, through which they can take down copyrighted material. If they’re smart enough to make that work, can social media sites really not stop hate speech? There’s just no financial incentive for them to take care of that.

Tell me about the decision to end with the blow-by-blow of some such online abuse you’ve suffered.

The books I’ve written in the past have been so goal-oriented—I had a specific aim to get younger women to identify as feminists, for instance. So it was interesting to write a book in which I didn’t know what the goal was—and that’s part of why it was important to me to not end this book with a neat bow. I wanted to show that abuse and objectification is an ongoing thing, an ongoing conversation.

I enjoyed the book’s non-chronological structure, and appreciated how you started with your first abortion at 27, went back in time to chronicle your younger life, and then recounted your second abortion—experienced at the same clinic—toward the end. How did you settle on this structure?

Overall, it was a really difficult decision. There was a part of me that wanted to work with more straight chapters, rather than essays, but it didn’t feel organic when I tried it like that. I realized the chapters were individual pieces that I wanted to stand on their own. But I knew from early on that I wanted to start with the abortion, and originally, my plan was for the second one to end the book. It [the latter] was such a big moment in my life because, as sad as I knew I was about to be, I knew I was also making a decision to live. When you grow up feeling objectified, rather than like a full, real person, to all of a sudden have this opportunity to say, I wanna be healthy; I wanna live; I wanna make this decision that’s best for me? I wanted to give that a lot of weight in the book.

Tell me about your process of writing this book. You clearly had a lot going on, what with your Guardian column, and your speaking engagements—to name what I’m sure is just some of what keeps you busy.

I don’t sleep [laughs]. I don’t have a particular routine; I’m not one of those people who gets up at 6 AM and writes ten pages. My life is too nutty. I have a full-time job and a five-year-old—I started this book when my daughter was three—so it was about taking moments wherever I could find them. My husband also works in media and works really hard, and early on, we made a conscious decision that our focus would be on our family and our work. So we don’t socialize much; we see our friends two or three times a year. Otherwise it would be literally impossible. I always hate the impression that having it all comes easy for people, because it’s really hard to work a job and also write a book. It’s hard to have a family and to try to be as successful as you can with your work.

Speaking of your family, this book is nothing if not super candid, especially concerning your home life growing up, and now. Tell me about your loved ones’ reaction to this book.

I think they understood the importance of the larger project, so they were cool, and obviously, I got everyone’s okay. My parents were super supportive—this issue is especially important to my mom. And my husband and I had a lot of conversations about my daughter and what would be best for her, and how she’d feel reading this at 15-years-old. I had a lot of mixed feelings about writing about her too much, but I knew some details about her were crucial to writing about the decision to have that second abortion, after she was already born.

So what’s next for you, writing-wise?

I have a couple of ideas I’m bandying about for next books, but nothing solid. For now, I’m really enjoying my writing at The Guardian and everything that’s going on with Hillary [Clinton], so to be honest, the election will probably take up most of my writing time through the fall.

Who are the memoirists or essayists who most inspire you?

Roxane Gay is the first person who comes to mind. I think her work has really shifted something in terms of that way that people are writing about feminism via their own experiences—she did something really important for the movement. I also love what Lindy West is doing. Again, it’s one of those things where it’s just really exciting to see women talking about their lives on their own terms, and creating their own narratives—which are not necessarily what’s shaped by the media or by other people. They’re doing it for themselves. And largely because of social media, they’re getting the support they weren’t getting ten years ago. So there, that’s the other side of the internet!

*

Sex Object: A Memoir is available through HarperCollins and Amazon.