This is the second post in an ongoing series about being a rookie bookseller and a slightly-more-than rookie writer. Read Part One here.

*

It can be hard, coming out of a three-year MFA program, to look around and realize it was all temporary.

Even as I’ve decided to commit to Ann Arbor for one more year, to the apartment I’ve been in for two years, to teaching at the university that bequeathed me my degree, all around me my people are deciding to leave. I don’t feel left behind so much as I feel that my landscape is evaporating, the Ann Arbor I’d signed up for no longer the Ann Arbor that remains. Not to say that my friends and classmates are just the boulders that sit quietly in the background of my life, but their disappearances have felt just as alarming as if such giant rocks, permanent fixtures in the earth, just upped and moved to Los Angeles one day.

I am far from treading water as I enter the notorious post-fellowship year—I padded my re-entry into the “real world” by staying involved in the community, signing on for summer teaching, and, of course, my bookseller position at Literati. Yet, there are days, often multiple in a week, where I feel untethered, as if I were the one who was moving away, the lone boulder rolling off.

The only stability and schedule in my life right now is my time at Literati. I feel lucky to have started working at this position a few months before my fellowship officially ended, so that now, instead of reeling about in so much newness, I instead have a place that is becoming more familiar every day. Still, I am uncomfortable and self-conscious about all the ways in which facets of the bookstore remain a mystery. Familiarity has become a fixation for me—even writing this blog series is an attempt to make this new environment as comfortable and known as my old MFA bubble. I want a shortcut to experience, an instant trick to acquiring the skills that can’t be taught but must be learned over years of making mistakes.

Which is why I came into this blog essay thinking I would write about the art and science of book-display. Watching the other booksellers fix a display was to believe that their knowledge was innate, like how a spider knows how to spin a web. I saw no hesitation, no overt calculation, and yet I was convinced there was something I wasn’t grasping, a key that would unlock the mystery of what book went where.

In pursuing my quest I learned a lot of great tips, some more intuitive than others. Don’t put two white-colored books together. Displaying a lesser-known author between two juggernauts will boost the rookie’s sales. Certain books are perennial favorites and will always have three or more copies in the store in case there’s a gap in the display. But what I didn’t get as readily was an answer to my original question—is it art or science? “I guess it’s both,” was the response I eventually pulled out of my colleagues. Unsatisfied, I persisted in asking, until finally I understood that I was never going to get the answer I wanted because I was asking the wrong question. I didn’t care so much if book-displaying taxed the left or right brain. I just wanted to know the right way to do the job.

Asking if it was science or art was my veiled way of asking if there was a formula I could follow, or an aesthetic that I could learn to replicate. Years of being in school and a teacher’s pet (but, like, a cool one) had convinced me with that there was a right answer, or at least a minefield of wrong answers. During my hours on the sales floor, every time I saw a gap, or needed to bump a book off the display, I was wracked by indecision. What if I made the wrong choice? The question plagued me, even as I reminded myself that any wrong choice was a temporary one. Bad book displays were changed by the more experienced into great book displays. But even great book displays did not stay the same day by day.

Book displays are by nature ephemeral. They are constantly changing, most obviously because, if they do their job right, people will buy the books on display. New books come out, old books are re-stocked, hardcover is replaced by paperback. Certain books don’t sell for weeks and lose their place on the display table to make room. Other books are suddenly reviewed by a bookseller and get back into the limelight. Every shift, I would arrive to a landscape that had been changed in small but innumerable ways. I would spend the first fifteen minutes of each new day re-familiarizing myself. In a weird way, the lack of permanence paralyzed me as much as if each decision were etched in stone. I felt that every move I made would be wrong out of sheer inexperience, and that I may never learn the right moves because the right moves were always changing. How would I ever feel comfortable working in a store where nothing stayed in the same place? How would I ever feel at home in a place where people were always leaving?

I was maybe conflating a few things—I was definitely overreacting.

*

One night, a few months into my position and at the top of the bell curve in terms of my anxiety, I was on the late shift with another new bookseller, a friend who had started only a week after me. We had been tasked with either continuing to add to a display for “Summer Reads,” or, if we felt up for it, coming up with our own concept and executing it in the last, empty hour before closing. We threw some joke ideas around—“Sands of Time: Historical Fiction” was a favorite—before we found one that just clicked.

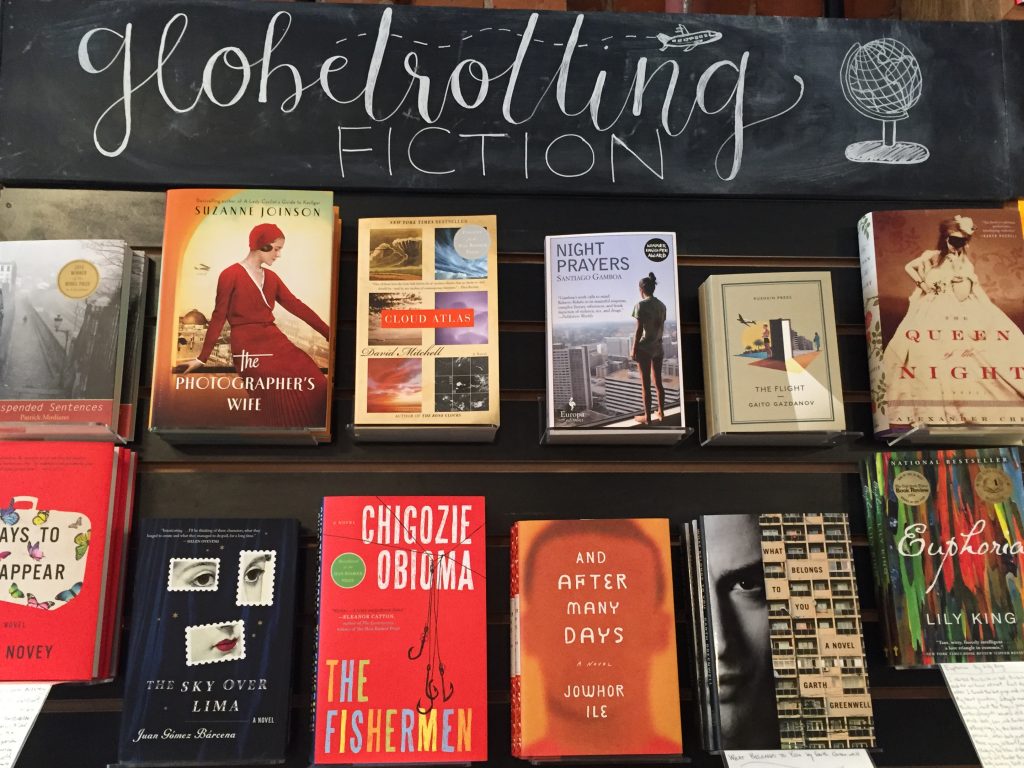

Globetrotting Fiction. Books that took its readers into unfamiliar countries—as good as a passport without the jetlag. We spent that hour before closing filling up the empty slots, shouting book names at each other, scanning unfamiliar texts for settings that weren’t the usual New York or San Francisco. Doubt and hesitation somehow stayed in their corners, visible but not yet encroaching. Every time I wanted to stop, to say that we were making a mistake, that we were giving everyone else a big mess to clean up, one of us would find another perfect globetrotting book. Still, as I watched my fellow bookseller chalk the banner atop our very first book display, I couldn’t help but say, “I’m sure all of this will be gone by tomorrow.”

“Who cares,” he said, as only a fellow rookie can. “We like it.”

And that was the thing—certainly there was an art and science to creating a popular book display, one that drew the eye to the right areas and boosted sales, but there was also the reason one took the time to learn the art and science in the first place. Personal interest. After all, when we came up with our first book display, I wasn’t thinking, “What would other people want to see,” but rather, “What would I want to see?” I’d unmoored myself focusing only on what I did not yet grasp, too impatient to see that I already possessed the one resource that really mattered. I was at Literati because I wanted to be a bookseller. All my anxiety and hesitation and endless attempts to avoid making any mistakes were all because I wanted to be a better bookseller. I wasn’t there because I’d hoped to replicate the safety of my previous environment. I wasn’t looking for a stable, no-brainer job. I had sought out the discomfort I was now shying away from—why hadn’t I remembered that?

And since I’d conflated the bookstore with Ann Arbor, there was a Siamese lesson to be learned there as well. Again, I had looked for a shortcut, thinking that I could skip the motion sickness of sudden change by staying put, not realizing that places would change whether I stayed still or not. But I had also forgotten that I was staying in Ann Arbor because I wanted to be in a new Ann Arbor. I wanted to experience Ann Arbor as a proper resident, and not a student, not a fellow, not someone with one eye on the next step and city. The moments of loneliness, of shifting routines as I said goodbye to friends and drinking buddies alike, were all part of the process. There is perhaps also an art and science to making a place your own—I’ll learn it in time.

Change, even sought-after change, can make us cling to what we’d hoped to leave behind. And in that initial clinging, that paralysis at the top of the diving board, you can start to believe that all you want is to be already in the calm water, the surface re-smoothed and the ripples subsided. But of course, the fun is in the fall, and the controlled chaos of broken, churning water. The fun is looking up to where you fell from and laughing at how scared you were, how impossible it had felt.

Two weeks have passed. Globetrotting Fiction is still there. Even better, it’s changing. A more fanciful banner has been chalked. Slots open up and books are switched out as other displays change around it. By never staying the same, Globetrotting Fiction has become an integral, and yet not way ever-lasting part of the bookstore’s ecosystem. One day, it will be gone, replaced by something better, but its ephemerality will have been much, much more satisfying than any kind of permanence I could create. I won’t forget how good it felt to finally take that leap and hope for the best. To open myself up to making mistakes. And whenever I see my display at the bookstore, whenever I remember where I was when the idea first popped into my head, all I can do is laugh and laugh and laugh.