Writing teachers don’t often look to massive tomes of biography for cutting-edge advice about the craft of creative writing. Small forms are more the rage — flash fiction, prose poems, novella series, micro-essays — and there are good reasons for that. These are forms that more obviously cross boundaries, are online-friendly, and easily readable for class discussions. A really good short-short is the our best friend.

In that context, a writer like Robert Caro might seem hopelessly old school, or even irrelevant to those of us who teach and think about writing for a living. The eighty-year-old Caro has spent most of his writing career on a single ongoing project, The Years of Lyndon Johnson, of which four volumes have been published to date. The shortest volume is 506 pages. The longest, Master of the Senate, runs 1,167 pages and looks like the stocky love child of a brick and a concrete block. The New York Times calls Caro the “last of the 19th century biographers,” which makes it seem as if Caro has outlived his natural readership by a hundred years or so.

But Caro’s recent interview in the Paris Review is a revelation. His work is built on intensive research through documents and interviews, as you would expect of a presidential historian or of the journalist that Caro was at the beginning of his career. But his writing style — and the intention behind it — would be immediately recognizable in a creative writing classroom. At a time when immersion is increasingly known as a powerful force in creative writing — a way to dive deep into a subject, to move beyond the immediate self into something larger — Caro is the most devoted example of what we might call an immersion biographer. He walked the paths that Johnson would walk to the Capitol as a congressman’s assistant, not just once, but over and over, at the same time, early sunrise, that Johnson did. To write about Johnson’s youth in Texas, Caro and his wife first rented an apartment in Texas, so that Caro, like a standard biographer, could have daily access to the documents at the Lyndon Johnson Library. During that time, he would drive out once or twice a week to the Hill Country, where Johnson was raised, for interviews.

But Caro’s recent interview in the Paris Review is a revelation. His work is built on intensive research through documents and interviews, as you would expect of a presidential historian or of the journalist that Caro was at the beginning of his career. But his writing style — and the intention behind it — would be immediately recognizable in a creative writing classroom. At a time when immersion is increasingly known as a powerful force in creative writing — a way to dive deep into a subject, to move beyond the immediate self into something larger — Caro is the most devoted example of what we might call an immersion biographer. He walked the paths that Johnson would walk to the Capitol as a congressman’s assistant, not just once, but over and over, at the same time, early sunrise, that Johnson did. To write about Johnson’s youth in Texas, Caro and his wife first rented an apartment in Texas, so that Caro, like a standard biographer, could have daily access to the documents at the Lyndon Johnson Library. During that time, he would drive out once or twice a week to the Hill Country, where Johnson was raised, for interviews.

That approach was limiting. Caro found himself in the same situation as legions of previous writers working on Johnson’s life: regarded as a dilettante who planned to drop in for a week, pick up some Texas details, and then write about the place as if they knew it. Unsurprisingly (as any person in a writing class sent off to “learn about a place” for a one-off assignment can tell you), the locals had no interest in selling off their lives so cheaply. So Caro moved to the Hill Country for three years. “When they realized that someone was finally coming to stay — to really try to understand them,” Caro tells the Paris Review, “All of a sudden they started talking to me in a different way, giving me a different picture of Lyndon Johnson, different from any that had been in any biographies before.” Caro’s immersion was not limited to being among people. With the prodding of Johnson’s cousin, Ava, he drove to the failed farm where Johnson’s father tried to raise the family. There, directed by Ava, he stuck his hands into the flimsy soil, which gave him a tactile understanding of why the crops did not take root.

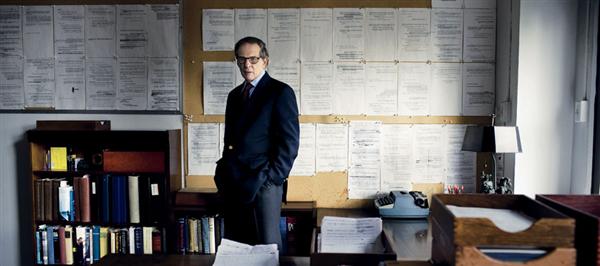

In profiles and interviews, Caro can come off as painstaking and obsessive in a way that would be incredibly difficult for most writers to replicate. He writes outlines that are the length of a book chapter all by themselves. He writes and then rewrites his drafts and rewrites at the copy edit stage and then rewrites whole sections in the page proofs, when most of us are resolved to just find missing commas. In this process, he has found support in ways that most writers do not. His wife, also a writer, serves as his research assistant. (She was also willing to move with him from Manhattan to Texas for the time that he lived there for research.) He has a supernaturally patient agent and editor. These individuals have received a return on their investment: Caro’s books have won two Pulitzer Prizes, three National Book Critics Circle Awards, and enough additional prizes, best-of lists, and personal accolades to fill an index.

But his success prompts a chicken-or-egg question. Each of his books takes nearly a decade to write. Did his ultra-meticulous process make its own logic — i.e., did the people around him come to believe this was the only way for him to write these books? Or, given space and support, did his process evolve in a way that shaped the books? We know that form and content are linked in significant, meaningful ways. But contemplating Caro’s work makes me think about how process and content might be linked, too. Do differing work habits make for different books? Put another way, how much does the nature of our writing project shape how we write it, and how much do our own writing processes — idiosyncratic for each of us, not just Caro — shape what the reader ultimately encounters on the page?

Speaking of form and content, what Caro shares with almost all creative writers is the belief that the sentences on the page must be linked to the emotional experience of the material. The man writes sentences. The enormous volume of his writing becomes even more significant when it becomes clear how much work he requires each sentence to do. His first book, The Power Broker, about the city planner Robert Moses, runs 1,344 pages. An additional 350,000 words (the length of about seven novels) didn’t make it into the book. (A side note: Caro describes himself as “naturally lazy.”) And each of those sentences is doing work.

Speaking of form and content, what Caro shares with almost all creative writers is the belief that the sentences on the page must be linked to the emotional experience of the material. The man writes sentences. The enormous volume of his writing becomes even more significant when it becomes clear how much work he requires each sentence to do. His first book, The Power Broker, about the city planner Robert Moses, runs 1,344 pages. An additional 350,000 words (the length of about seven novels) didn’t make it into the book. (A side note: Caro describes himself as “naturally lazy.”) And each of those sentences is doing work.

In the Paris Review interview conducted by James Santel, Caro describes the problem — a writing problem — of trying to convey the enormity of Moses’s effect on New York State. The subject matter did not lend itself to sexiness. His publisher did not expect a bestseller. Of the book, Caro says, “It matters that people read this. Here was a guy who was never elected to anything, and he had more power than any mayor, any governor, more than any mayor or governor combined.” So he needed to write in a way that communicated what Moses had done. A list of all the major highways that Moses built in and around New York carried the facts but none of the power. Caro asked himself, “Can you put the names into an order that has a rhythm to it that will give them more force and power?”

Recognizing the potential of sentence rhythm — that’s an idea that would feel at home in any creative writing classroom. Here’s what Caro wrote, in the introduction to The Power Broker:

He built the Major Deegan Expressway, the Van Wyck Expressway, the Sheridan Expressway and the Bruckner Expressway. He built the Gowanus Expressway, the Prospect Expressway, the Whitestone Expressway, the Clearview Expressway and the Throgs Neck Expressway. He built the Cross-Bronx Expressway, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, the Nassau Expressway, the Staten Island Expressway and the Long Island Expressway. He built the Harlem River Drive and the West Side Highway.

That’s four sentences, listing the names of four, five, five, and two roads, respectively, with the beat of the word ‘expressway’ repeated until the last sentence, when the rhythm changes for effect. It builds and then stops short, communicating the massive snarl of roads around the city, the pounding of the cars on them each day — a city that is full of roads that will never have enough.

Caro’s writing is linked to a deep moral obligation to get the story right, not just as an unassailable set of facts, but as something more democratic, as strange as that might be to say about a set of giant books about the elites of the country. His books are ultimately about power. But as Maggie Nelson said during a recent talk at AWP, “Every book invokes its own ghost.” Around a book about power lingers the ghosts of the powerless. Caro knows this. He says, “Somewhere in The Power Broker I write that regard for power means disregard for those without power. I mean, we’re really talking about justice and injustice.”

Caro’s goal is to illuminate how power works in our country, so that we can recognize it when it is wielded around us. For this, facts are not sufficient. He says, “Rhythm matters. Mood matters. Sense of place matters. All these things we talk about with novels, yet I feel that for history and biography to accomplish what they should accomplish, they have to pay as much attention to these devices as novels do.” To see these devices at work in biography, in history, in works outside what we usually read in creative writing classrooms — it reminds us, as writers, and as teachers of writing, just how valuable these tools are. They are not just aesthetic instruments. They are deeply connected to issues of power and justice. As creative writers, we spend a great deal of time learning how to employ these tools. Caro’s work reminds us why — and for whom — we are employing them.