I’m drafting a new course description for my undergraduate writing class, and on a piece of paper, I jot down everything I value and wish to impart to my students: clarity of language, a sense of movement, style, voice, vision, complexity, compassion—

Compassion?

It’s true that—especially lately—this has become a key criterion for determining whether or not I continue reading a piece of literature. Do I detect in the writer not only wit and intelligence, but wit and intelligence rooted in kindness? Is there wisdom being shared about human beings—of our mutual frailty, of grace in the midst of despair?

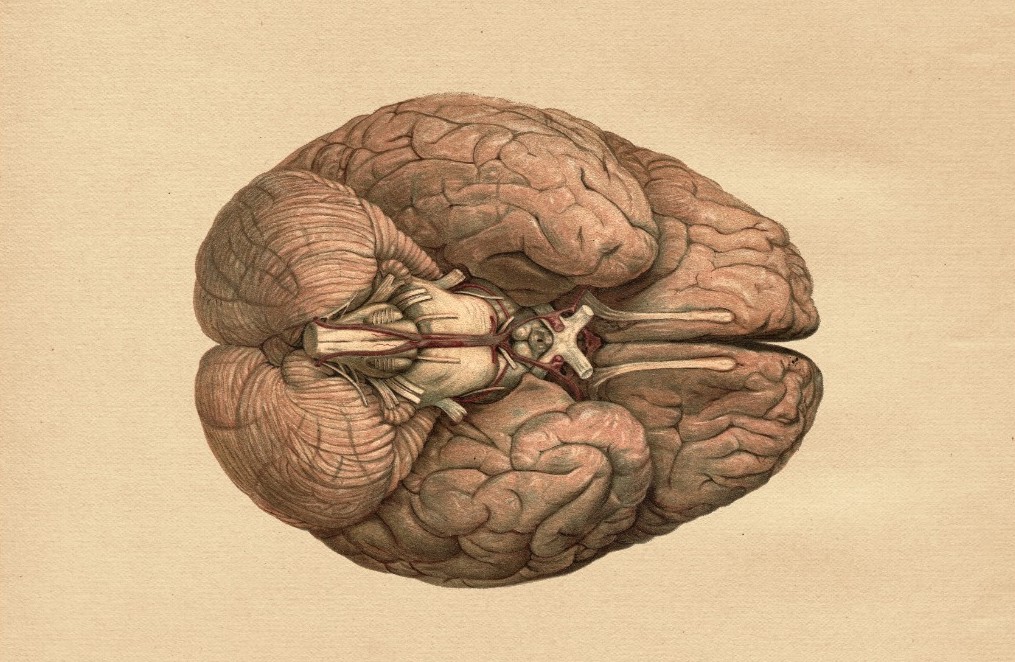

I have, in the past, incorporated some scientific studies showing functional MRI scans of the brain when it’s processing fiction. Some research has found that we perceive things happening to characters we read as if they are real. There’s no difference, for example, between reading about someone smelling a bouquet of flowers and actually smelling one—the olfactory cortex lights up in the same manner. I also provide psychological studies finding that frequent readers of fiction are able to understand other people better, to empathize and see the world from multiple perspectives.

In the first instance, the lesson is about using metaphors that evoke the senses—to stimulate different parts of the brain and thus create a more lasting mental impression. It is a craft lesson. In the second instance, the point is about how the writer herself needs to be empathetic in order to create fiction with which readers can empathize. I know; this is a pedagogical leap of faith that’s not really supported by the research.

But why do I try? Why do I cheat my way in order to convince? Why do I even use science?

I’ve always been afraid of what I call voodoo creative writing lessons. When I first took a writing course at a community college, I was turned off by the teacher’s dispensations. “Write from experience.” “Listen to your heart.” “Don’t shy away from the pain.” I equated them with a lack of expertise and a general laziness to probe writing theories deeply. The result: I switched my major to something I thought was more practical and concrete: screenwriting. I’ve since emphasized craft and technique. I’ve consulted so many advanced books on the topic.

Today, when I read student work that relies on a clever conceit—such as a piece of fiction that is, ultimately, an elaborate joke; when I read stories that are technically functional but devoid of insights, I cringe. I prefer a piece that is overly sentimental but that is trying to get at something true to the undergraduate’s experience, such as love, longing, heartbreak.

Am I just becoming softer as I age? After experiencing my own losses and setbacks, am I perhaps becoming resentful of literature that doesn’t reflect those things? But who am I to impose my own preference (and indeed reality) on my students? Isn’t the cardinal rule of teaching creative writing that one must not dictate the content of the piece?

I want to say that the best writers are those who live kind and compassionate lives. I want to say that instead of focusing on your revision, you should instead sit down and meditate, go out into the world and practice mindfulness. Then when you come back, you can surely write better stories and poems.

But who am I kidding? For every writer belonging to the path I advocate, there are probably ten famous, successful ones from the School of Douchebaggery. And last I checked, books that entertain are far more popular than books that move the spirit.

Is this an either/or proposition then? Probably not. But here’s another likely truth: Most of the students I teach will not go on to publish anything significant in their lives. Many are going to forget the craft lessons on the day the semester ends. If I, as a result of teaching creative writing, cause any of them to become more honest, kind, and empathetic human beings–well, shouldn’t that be enough?