Here are three new titles that have come out in the first quarter of 2016. I talk about them in terms of what craft gems they may teach us as writers.

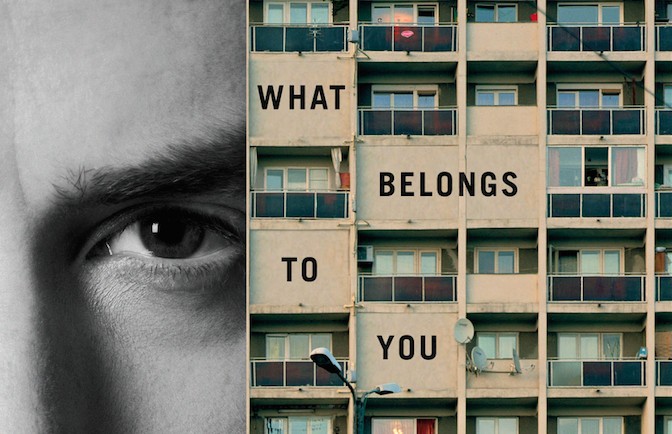

What Belongs to You

Release Date: January 2016

Publisher: FSG

Garth Greenwell is a master in the use of the retrospective voice—weaving the narrative in and out of the present to the past and back, slowing time, hastening time, incorporating insights from the point of view of a conscientious yet lonely gay expat. The narrator is an American teacher in Bulgaria who becomes involved with the charismatic hustler Mitko, meeting him first at a public bathroom, then over the course of a few months, in the narrator’s own apartment. The observations are keen and specific, and one cannot help but feel the patient hand of the storyteller.

The use of foreign language in this book is worth mentioning—Greenwell includes Bulgarian not just as a cheap device to evoke place (although it does lend the story much realism and authority). The words are deployed with poetic precision: such as in the rhythm of chakai, chakai, chakai (wait, wait, wait); they are used to characterize people, such as Mitko’s love for the word podaruk (gift); and to reflect the narrator to make sense of his world (strahoten means awesome, a word “built from a root signifying dread”). Most importantly, it is used to cut deeper into the core of the narrator’s emotional question: priyatel means both friend and lover—which one is he really to Mitko?

Dialogue is not separated by quotation marks; rather, it is folded into narrative—the effect: a recollection that allows for heightened language as well as heightened subjectivity. A remarkable scene can be found on page 157-171, revolving around the narrator and his mother observing a boy and his grandmother while inside a train. Tender and painstakingly rendered, the chapter is a lesson on how to make the imaginary real.

A Doubter’s Almanac

A Doubter’s Almanac

Release Date: January 2016

Publisher: Random House

Reading Ethan Canin’s novel is a demonstration of all his craft commandments (taught at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop) in motion. Most palpable is his edict on “scene hygiene”—a particularly doctorly way of saying that scenes should be written tidily: enter as late as possible and exit as soon as the emotional point is made. While this might lend itself to a certain stylistic flavor—especially vignettes, which are reminiscent of some of Canin’s favorite books, such as Evan S. Connell’s Mr. and Mrs. Bridge novels—it’s hard to argue against its efficacy. The plot moves fast but never prematurely; A Doubter’s Almanac is built scene by solid scene, until the weight of the emotional question (another Canin terminology) bears down and squishes the air out of your gut.

Canin has mentioned that by default, he’s used to writing through only one character’s POV per story—though, to be sure, that POV is usually, astonishingly, like the Mariana Trench (“The only way a writer can fail is to not go deep enough” and “You must deeply imagine…” being some of his favorite sayings). Ostensibly, the novel is divided into two parts: the first about the early childhood and the rising career of mathematician/topologist Milo Andret; the second about his son, Hans, who witnesses the tragic decline of the father. One can argue, though—without taking away anything from Canin’s ability to write—that the novel is really still told through one POV: It is Hans’ throughout.

For me, the takeaway from the novel is how utterly convincing Canin makes you into believing that you know—that you’ve lived through, really—the life and inner workings of an obsessive, mathematics genius. You come away loathing Milo Andret for all his human flaws, the way he treats his family, etc., but still cannot help yourself from siding with him.

You Should Pity Us Instead

You Should Pity Us Instead

Release Date: February 2016

Publisher: Sarabande

In this collection of eleven short stories, Amy Gustine shows off her ability to play with POV and the idea of narratives driven by certain conceits. Each story is cleverly set up to a what-if scenario that traverses time, race, class, religion—from an Israeli woman sneaking into Gaza to reclaim her captive son from militants (“All the Sons of Cain”), to a doctor in nineteenth-century Ellis Island who plays God by deciding which immigrant gets into the country (“Goldene Medene”). Many of the stories are bold and often successful experiments in POV shifts, refining the distinction between a third person omniscient and a roving third person close. But my favorite, the title story, “You Should Pity Us Instead,” actually uses the more traditional third person close POV throughout. Here, we see a conservative suburb of Ohio through the eyes of Molly, who recently moved back with her husband and their family from Berkeley. The setup alone promises great moments of humor and conflict, with the differences in values driving much of the characters’ bad behaviors. And in this story Gustine delivers wonderfully—the deep POV, perhaps, allowing for much-needed pathos.

The way time is handled in this collection is also something to be studied. Though slightly conventional, the use of “triggers”—things or events that remind and therefore transport POV characters back in time—isn’t held back; it is probably a testament to the technique’s efficacy. The story “Unattended” is especially replete with these: the narrative moves between Joanne’s life as a mother of an eight-month-old baby, and her own childhood—the two timelines connected by her experience of an ear infection. Some of the shifts to backstory can perhaps feel a little forced at times, but for the most part, Gustine makes them invisible, the underside weave of an exquisite fabric.