At the end of her book of essays Madness, Rack, and Honey, Mary Ruefle offers a collection of twenty-two short lectures. While the longer essays that compose the book are evocative and stirring (my favorite is titled “Someone Reading a Book is a Sign of Order in the World”), it is in this abbreviated form where the book’s magic unfolds. Perhaps this is because the pieces read like mantras or dictums, easy enough to memorize but requiring dedication to unpack. Perhaps it is because of the irony of the project; that a “lecture”—that form we so often associate with lengthy didacticism—is here presented with a brevity akin to a tweet.

Whatever the reason, I find myself enchanted by these concise kernels of narrative addressing everything from hypocrisy to the brain to living alone. But it is the page titled “Short Lecture in the Form of a Course Description” where I find myself routinely returning. It reads:

“My idea for a class is you just sit in the classroom and read aloud until everyone is smiling, and then you look around, and if someone is not smiling you ask them why, and then you keep reading—it may take many different books—until they start smiling, too.”

Perhaps it is because I am on the academic job market right now, or perhaps it is because I am in the middle of teaching three different classes in three different genres at three different institutions, but there is something about the class Mary Ruefle describes in “Short Lecture in the Form of a Course Description” that makes me want to radically simplify my approach to teaching creative writing. Of course, on first glance, Ruefle’s class is problematic because it is pedagogically flawed: it seems to assume that the function of reading is to entertain when we know this is not true—good courses, populated by evocative readings, disturb conventions and disrupt assumptions in healthy ways, prompting not smiles but dropped jaws or raised eyebrows or even, yes, frowns.

But having been asked quite often lately to articulate what it is I do in the classroom, and therefore, what creative writing does in the world, I am starting to wonder if my teaching already aims for some version of what Ruefle articulates here. I want my students to read—published work and peer work, work in the public sphere and work that lives underground—until they reach a state of catharsis, until the text enters them in such a way that produces a visceral response. And then, I want my students to create that same phenomenon in the minds and bodies of their readers.

In a recent conversation with a fellow prose writer, I articulated my frustration with writing my artist statement, one of the many documents I crafted on the job market this past fall and one I am still revising. (Is an artist statement ever done?) I told her while I know my work is interested in the relationship between artistic practice and social justice, I don’t yet know what that relationship is. She put down her glass and blinked at me as though I had asked her if paper was thin, then proceeded to tell me that while art itself might not be capable of instituting change in the world, it creates the space for change to be imaginable. It strikes me now that this, too, is our work in the creative writing classroom—that we are endorsing a diverse and varied chorus of story to enter the archive in order to widen the scope of the human imagination. In order to make change imaginable. In order to make possible more.

Perhaps the students in Ruefle’s proposed course aren’t smiling because they’re being entertained. Perhaps they are smiling because they are imagining an infinite number of potential narratives to inaugurate into the literary record, smiling knowing that they have—through the site of the creative writing classroom, a space that grants students permission through the vulnerability of the workshop (which endorses a culture of getting it wrong because there’s no getting it right) and the necessity of revision (which forces us to face and resolve our work’s faults and failings)—been invited to compose narratives that matter, stories that do work in the world. Through the teaching of creative writing, we sanction curiosity (that sadly old-fashioned idea), and it is curiosity that raises the questions that institute change. For the creative writing classroom does not ask students to translate lived experience to the page; rather, it requests that students speculate, invent, and imagine all possible lives and all possible worlds. It asks students to carefully consider the potential of the word perhaps.

For my next job talk, maybe I’ll take a note from Mary Ruefle. Maybe I’ll just say this:

Short Lecture on Creative Writing

Read. Read widely and read deeply and diversely and read to know where you come from as a writer and to whom you are writing. Read until the practice of reading feels like part of the art of writing, until you come to realize that reading is not an act separate from writing, but that they are one and the same.

Then, when you have read until reading feels like writing itself, charged and haunted by the voices that compose the literary archive, write the book you think cannot be written.

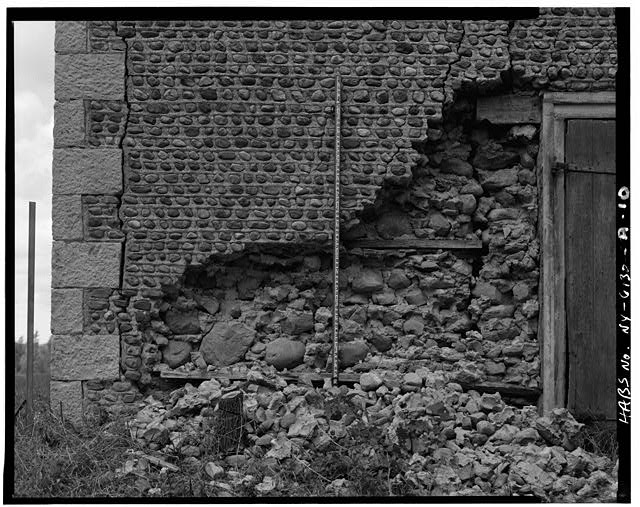

Image: “Detail of South Front Wall Failure. Hiram Lay Carriage House, Mays Point Road, Tyre, Seneca County, NY.” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog.