By the time one of saxophonist Wardell Gray’s most blazing recordings came out in 1956, Gray was dead, his body found on the side of the road outside Las Vegas. He was thirty-four years old.

Gray was one of the West Coast’s most talented jazz musicians. Raised in Detroit, Michigan, he settled in Los Angeles in a thriving bebop scene and played with everyone from Erroll Garner and Billie Holiday to Dexter Gordon and Zoot Sims. Versed in swing and bop, Gray did TV spots. He released his own records and mentored younger musicians like Hampton Hawes and Art Farmer as they established themselves. When Bennie Goodman heard Gray play in 1947, he hired him to join his new modern band. When pioneering bop altoist Charlie Parker recorded a new blues to commemorate his release from Camarillo State Mental Hospital, he had Gray play on it; “Relaxin’ at Camarillo” became a jazz standard.

Musicians loved Wardell. They loved his sound. He and baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams were close friends, trading novels and watching movies between gigs together, and sharing each other’s instruments. “I guess people don’t consider there are jazz musicians who are well-read and read for pleasure,” Adams remembered. “And I was going to university at the same time, pursuing an English major. Wardell was very interested in what I was doing at college.” Gray was playing with Count Basie when he fell in love with his second wife Dorothy A. Duvall. When Gray and Duvall got married in 1951, trumpeter Clark Terry was his witness. Terry nicknamed him “Bones” for his thin, 6’4″ frame. When they buried Gray in Michigan four years later, Pepper Adams was a pallbearer.

People have been speculating about Wardell’s death since the police closed the case in 1955. The mixture of music and high drama, the lingering mystery of unanswered questions, and the midcentury setting lends itself perfectly to a noir treatment. But this rich material is someone’s life we’re talking about. Gray was someone’s son, someone’s husband and father. From the perspective of narrative, though, the questions are too tempting to resist: Who was he? What was he up against? What happened to him?

Best-selling crime novelist James Ellroy mentions Gray’s murder in his 2001 novel, The Cold Six Thousand. Jack Kerouac references Gray in On the Road, writing how two beats, “sandwich in hand, stood bowed and jumping before the big phonograph, listening to a wild bop record I had just bought called ‘The Hunt,’ with Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray blowing their tops before a screaming audience that gave the record fantastic frenzied volume.” Author Bill Moody, a jazz drummer himself, turned Gray’s story into his 1995 novel, Death of a Tenor Man. In it, a detective searches for evidence of foul play in a case that cops deemed an open and shut case. Both books are hard boiled crime stories, and even though they focus on the unfortunate, more tawdry side of jazz and Wardell’s life, they do the great service of keeping Gray’s name in circulation, so that as jazz music ages and Gray inevitably fades from view, hopefully at least a few people will continue to discover his music. Other writers have turned jazz history into compelling fiction.

Elliott Grennard based his short story “Sparrow’s Last Jump” on an infamous 1946 recording session Charlie Parker did for Dial Records. The story appeared in Harper’s in May, 1947. Grennard sat in the session as a correspondent for Billboard magazine. Parker came in, struggled with his instrument, struggled to tune up. He played a few legendarily sloppy renditions–including “Lover Man,” one of the most poignant, anguished songs he ever recorded, and often considered his worst because he’d drunk a quart of whiskey and been prescribed Phenobarbital–then he left the studio. Ross Russell was such a huge Parker fan that he started Dial Records in order to record Parker. When Russell saw Parker’s condition in the studio that day, he said, “I’ve just lost a thousand bucks tonight.” Russell physically propped Parker up during “Lover Man.” He also released “Lover Man” anyway.

The saxophonist never forgave Russell for releasing music made at his lowest, yet despite its flaws, bassist Charles Mingus called “Lover Man” one of his favorite Parker songs “for,” in his words, “the feeling he had then and his ability to express that feeling.” As scholar Ted Gioia put it in his book West Coast Jazz, “The performance is pathetic, but the pathos is gripping: It is a record that few can enjoy, but once put on the turntable it is mesmerizing.” I find Parker’s playing on it hauntingly beautiful, too, filled with raw emotion that’s not simply tortured but reaching, calling out, and charged with a gripping blue agony that’s missing in even the most melancholy ballads.

To salvage some studio time, Russell kept the rest of the band playing after Parker left. Out in Los Angeles, Parker powered on. He’d been using heroin for years and often drank heavily when he couldn’t score. A mix of drug withdrawals and alcohol abuse, rather than mental instability, sent Parker off the deep end. Twice he staggered into the lobby from his room in the Civic Hotel, naked except for his socks. When he lit his hotel room on fire, likely from falling asleep smoking, the police arrested him for arson and indecent exposure, held him in the Los Angeles County Jail psych ward, then transferred him to Camarillo State Mental Hospital where he spent six months sober, recuperating. He commemorated the experience in his song “Relaxin’ at Camarillo,” transforming real life into music the way Grennard transformed real life into fiction.

This period was one of the worst in Parker’s life. Grennard turned it into literature. Russell turned it into an enduring musical statement. Is that exploitive? Opportunistic? Or is a musical genius’s agonizing story worth more to the world than their personal privacy? Parker was one of the world’s most influential musicians. People remain fascinated by his brilliance, mystified by his lifestyle, and want more from him than just the music. We want him. It’s hard for writers to resist a good story, and maybe the world needs to know what makes brilliant artists tick in order to see what makes us all tick. Although we must pry within reason, peering into people’s private lives and interior worlds is what makes literature so rich and engaging.

There are a few good jazz movies based on real themes and history: Paris Blues, featuring Sidney Poitier and Paul Newman in 1961, Shirley Clarke’s dark underground classic The Connection in 1961, and Round Midnight in 1986, with sax player Dexter Gordon playing the lead, are the best. Good jazz fiction is harder to come by.

California novelist James Houston tried his hand in 1969. It’s called Gig and takes place in a coastal California roadhouse. As the dust jacket copy says, it’s “the story of one Saturday night around Roy’s grand piano, of the people who come to listen and perform, and of the relationship between a performer and his audience.” Kazuo Ishiguro published the story collection Nocturnes, all built around music, one focused on jazz. One of the most celebrated examples of jazz literature is Michael Ondaatje’s novel Coming Through Slaughter.

Published in 1976, Ondaatje’s book is based on the life of New Orleans cornetist Buddy Bolden. Bolden was a famously inventive player who led an infamous life. In New Orleans, he and jass forefathers King Oliver, Louis Armstrong and Bunk Johnson helped shape jazz into the distinct form of music we know it as today. He invented a marching band beat called the “Big Four” which facilitated more improvisation. He played for enthusiastic crowds of people in the streets. Then he disappeared for two years, suddenly reappeared with even stronger musical chops, and at age thirty went what people called “mad” in a parade. He spent the rest of his life in an asylum. None of his recordings survived.

Ondaatje’s book is timeless, partly because its humanity, formal experimentation, and themes transcend jazz. The author knew a strong protagonist when he saw one, and his fictional Bolden only partially resembles the thin portrait of Bolden historians have. It also rises to an archetype of the wild musical genius, the artist as comet streaking through earthly skies, bright and illuminating, intense and brief, attractive and mystifying, and also confusing. It portrays artists as powerful fragile beings, buckling under our shared mortal pressures while crafting things that live beyond this world and most of our abilities. For many writers, the historical record isn’t the point. They don’t need all the answers. They’d rather experiment with the incomplete picture in order to build a new, bigger truth in the space between details.

All of which is to say, readers looking for something compelling to spend time with should consider the small pantheon of jazz fiction. Writers looking to turn real life into dramatic narrative need look no further than the real history of American music. Racism, resistance, creativity, invention, the power to shape global culture while enduring systematic repression, violence, drug use, and the countless personalities with memorable names set against the sprawling canvas of post-WWII New York City, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles–it’s all there. Hopefully, more people will write their own jazz stories. The players are deeply human, talented and flawed, like Parker, Holiday, and Gray.

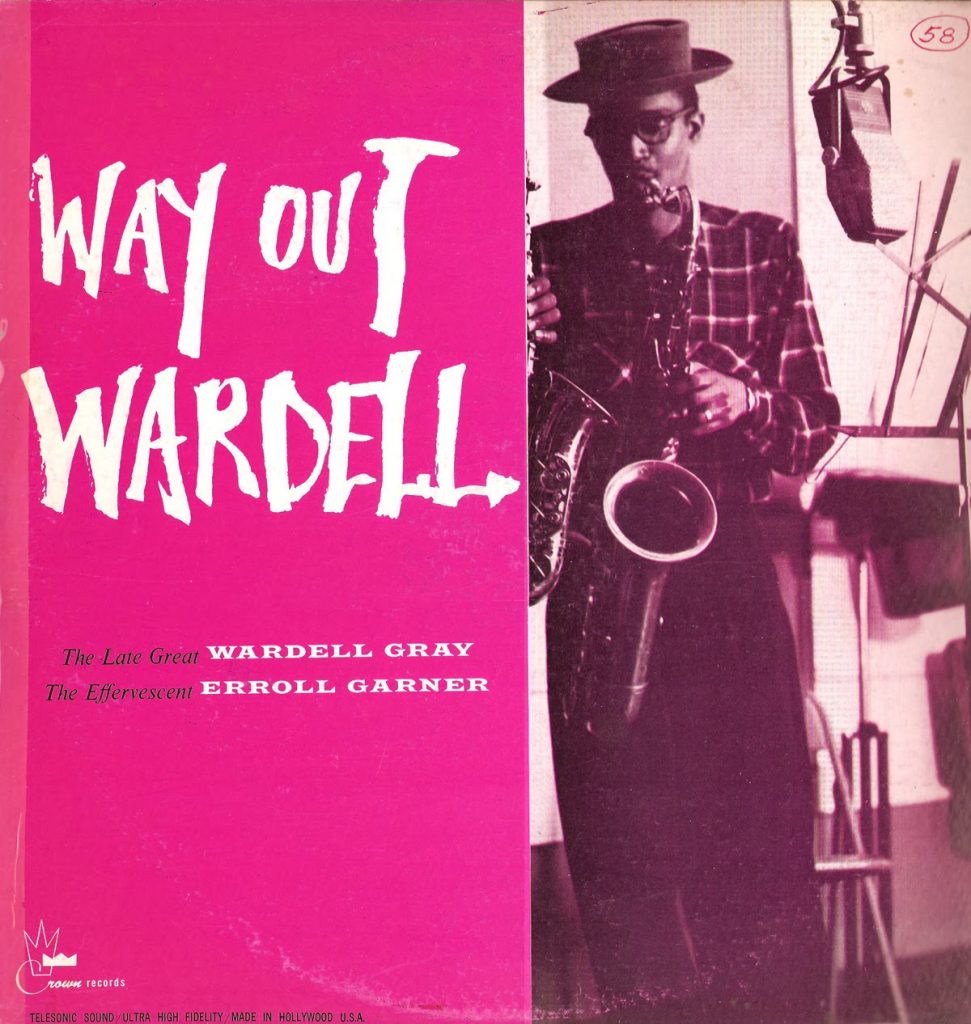

In 1956, LA’s Modern record label released what many consider some of Gray’s best music. The recordings were taped live at two concerts in 1947: one on February 27 at Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, the other on April 29 at the Civic Auditorium in Pasadena. The songs appear on Way Out Wardell. You can hear Gray’s inventive mix of swing and bop on “Just You, Just Me” and “Sweet Georgia Brown.” They’re the kind of solos that might sound standard now, but in the days when new forms of jazz were emerging from big band, these were virtuoso performances that blew peoples’ minds. The tired image of the guy with the horn smoking the cigarette on the street corner, the muted trumpet moment on the movie soundtrack–these tropes have inured us to the actual sound of jazz, but stop for a second and listen. Really listen. Solos like Gray’s and Parker’s are the kind that make the impossible seem casual. They’re the skateboarder doing a crazy triple flip on a ramp despite gravity, before we’d seen that a thousand times. They’re the first moon landing and the millions of people watching the event on TV from their living room sofas. They’re an unscripted feat that pushed the limits of what music could be.

In 1956, LA’s Modern record label released what many consider some of Gray’s best music. The recordings were taped live at two concerts in 1947: one on February 27 at Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, the other on April 29 at the Civic Auditorium in Pasadena. The songs appear on Way Out Wardell. You can hear Gray’s inventive mix of swing and bop on “Just You, Just Me” and “Sweet Georgia Brown.” They’re the kind of solos that might sound standard now, but in the days when new forms of jazz were emerging from big band, these were virtuoso performances that blew peoples’ minds. The tired image of the guy with the horn smoking the cigarette on the street corner, the muted trumpet moment on the movie soundtrack–these tropes have inured us to the actual sound of jazz, but stop for a second and listen. Really listen. Solos like Gray’s and Parker’s are the kind that make the impossible seem casual. They’re the skateboarder doing a crazy triple flip on a ramp despite gravity, before we’d seen that a thousand times. They’re the first moon landing and the millions of people watching the event on TV from their living room sofas. They’re an unscripted feat that pushed the limits of what music could be.

The end of Gray’s life goes like this: In 1955, the Benny Carter Orchestra hired him to play on the opening nights of the Moulin Rouge. The Moulin was the first racially integrated hotel-casino in America, and they were going to celebrate with great fanfare. Carter’s band played three times a day. Customers flocked to the casino. On the Orchestra’s final day, Gray didn’t show up to one performance. He missed the late night performance, too. No one knew what was up. The following day, a stranger found him with a broken neck in the weeds on the side of the highway four miles outside of Vegas. Clearly he’d died elsewhere and someone had moved him, but nobody could figure out why, or who.

Vegas was a mob town, a racially charged town. Money ruled. Sex, alcohol, and power played heavily, too. With so many poisons running through its green veins, it’s hard to imagine its white police force pursuing the ugly truth about the death of a young black man, even one of Gray’s visibility and renown. The autopsy describes Gray’s injury as a “fracture of the 5th and 6th cervical vertebrae with resultant injury to the spiral cord” and “contusion of the brain due to blow on head,” or at least the novelized version does. To the question of how the injury occurred, the death certificate states: “Fall on cement floor.” Wardell was buried in Detroit, Michigan where he grew up. The Las Vegas police closed the case.

People speculated: murder, racism, a love triangle, drugs. Maybe the white powers that be were trying to stop a black business of that size from succeeding. The Moulin Rouge did close within a year of opening. Either way, “Fall on cement floor” seemed too easy an explanation for the loss of someone this talented.

In West Coast Jazz, Ted Gioia provides a verifiable account of Gray’s death. Like many jazz players at the time, Gray had started using heroin. Overdoses killed many of them, including pianist Sonny Clark and saxophonist Ernie Henry. Some people suspected Gray owed drug dealers money. Others speculated that he’d been messing around with another person’s wife or girlfriend and got snuffed out. According to a dancer friend who was partying with Wardell on the night of the final shows, Gray shot heroin and fell off his bed, breaking his neck. Instead of trying to revive him or find medical help, he panicked. As bassist Red Callender put it: “If the guys he was with had any brains they would have taken him to a hospital, they could have saved him. Instead, he died and they dumped him in the desert. . . .Had he lived he would have been one of the truly amazing players of our time. He was anyhow.”

Gray died on May 25, 1955. I was born on May 25, 1975. I was raised in Phoenix, Arizona, and I know the desert Gray died in well. Since I discovered his music, I’ve tried to take a moment to think of him on my birthday, not the waste of his life, but the success of it. He packed a lot in, so I privately pause to acknowledge that he walked the earth long enough to leave a tail of moving music as long as Haley’s Comet, a tail which still streaks our mortal skies, even after he passed around the curve of this earth, out into darkness.