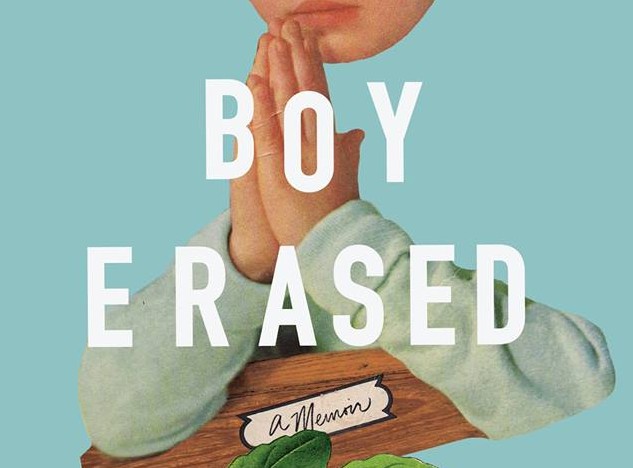

In 2004, Garrard Conley was outed by a classmate and given an ultimatum from his family: “cure himself” of his homosexuality or lose their support, financial or otherwise. At nineteen, he consents (a tricky word here) to conversion therapy at Love in Action, an “ex-gay” Christian ministry program. What ensues is a harrowing journey that is mired by shame and confusion–where Conley is made to trace his sin through his family tree as if it were a genetic condition, where he is forced to question his faith and the qualities that have thus far constituted his personhood–but that ultimately culminates in an unexpected turn of empathy. Twelve years later, Conley has emerged from his experiences with a memoir, Boy Erased. Its prose is lush and gorgeous, particularly in Conley’s depictions of Arkansas and the South as a whole, and the structure zips and looms in a way that seems to draw upon the very nature of trauma.

What is so stunning about Boy Erased is the fact that the nineteen-year-old Conley we meet is vivid and arresting, even as he sinks into a depression, even as he loses touch with the very things that constitute his sense of self. It’s in part Conley’s deft hand with prose, in part his ability to transcend trauma to render an honest, visceral picture of himself. “And who was I before Love in Action?” Conley writes. “A nineteen-year-old whose second skin was his writing, whose third was his sense of humor, and whose fourth, fifth, and sixth were the various forms of sarcasm and flippancy he had managed to pilfer from his limited contact with English professors during freshman year at a small liberal arts college two hours away from home. Remove the skin, and I would be no safer from the threat of suicide than T. Remove the skin, and there was nothing but an ache to fit squarely into my father’s lineage, into my family. According to LIA logic, the only option was to convert, smother one’s former self in the branches of the family tree, and emerge, blinking, into a Damascene sunrise.”

What is so stunning about Boy Erased is the fact that the nineteen-year-old Conley we meet is vivid and arresting, even as he sinks into a depression, even as he loses touch with the very things that constitute his sense of self. It’s in part Conley’s deft hand with prose, in part his ability to transcend trauma to render an honest, visceral picture of himself. “And who was I before Love in Action?” Conley writes. “A nineteen-year-old whose second skin was his writing, whose third was his sense of humor, and whose fourth, fifth, and sixth were the various forms of sarcasm and flippancy he had managed to pilfer from his limited contact with English professors during freshman year at a small liberal arts college two hours away from home. Remove the skin, and I would be no safer from the threat of suicide than T. Remove the skin, and there was nothing but an ache to fit squarely into my father’s lineage, into my family. According to LIA logic, the only option was to convert, smother one’s former self in the branches of the family tree, and emerge, blinking, into a Damascene sunrise.”

In all, Boy Erased is a stellar debut from a subtle and compassionate voice in memoir. It celebrates the ambiguities of love, of sexuality, of identity.

Recently, I was able to talk to Conley about Boy Erased, the importance of nuance, the inherent activism of literature, and the queen herself, Flannery O’Connor.

*

At the end of your book–in fact, in the acknowledgments–you tell the story of the inception of Boy Erased. That is, that you pitched it at a party after a few chance encounters before the book really existed. While pitching nonfiction when the project is just in the idea phase is rather common, had you attempted to write about your experience at LIA before?

I had often tried to turn Boy Erased into a comedy or a sprawling family drama. The problem with these earlier iterations is that they lacked truthiness or even what Nabokov called the “shimmering go-between.” I couldn’t enter the story to find that magic spot because, as it turned out, the only way to enter the story was to enter the trauma that I had ignored for so many years. Brainwashing will do that to you. I had also been taught by my counselors that writing the kinds of stories I wanted to write was somehow sinful. (I wrote stories with strong female narrators.) These counselors took away my notebook on my first day at the facility and told me it was a “distraction” to think creatively. On top of all of these problems, I also worried that my memories might be suspect. In order to clear the cobwebs, I had to have long conversations with my mother about what she remembered, and all of this was extremely painful. Writers know that memory is unreliable, but I was faced with deliberately compromised memory, denial, and suppression. However, about ten years after my “escape” from the facility, I began to feel intrigued rather than terrified by the idea of compromised memory. I saw unearthing these memories as a project that could benefit not only myself but the people around me, hopefully even others who went through the “ex-gay” process. I wanted to create a living–and flawed–document of what these people, in this specific historical moment in our country’s history, did to the minds and bodies of their patients. I wanted my book to be something that would speak from its intense subjectivity into some more universal truth about power and oppression. This realization turned any initial comedic or fictional aspirations into dead seriousness.

It’s interesting that you mention your desire to turn the events that inspired Boy Erased into a comedy. Because as I was reading the book, I realized the only other piece of media about the “ex-gay” process I could think of was But I’m A Cheerleader!, which is this incredibly campy satire about a teenaged girl sent to a camp to “cure” her lesbianism. And I’m not trying to devalue the movie, which did a lot of work as far as portrayals of queer characters. But it’s something I’ve been considering–our reflexive tendency as artists to want to sublimate trauma into humor, to repress tragedy until it becomes comedy because it might feel safer. And your TedxBG talk on your experience at Love in Action was very funny, it had a lot of dry humor. Would you say there are different kinds of power, different stakes even, in these different sorts of portrayals?

It’s interesting that you mention your desire to turn the events that inspired Boy Erased into a comedy. Because as I was reading the book, I realized the only other piece of media about the “ex-gay” process I could think of was But I’m A Cheerleader!, which is this incredibly campy satire about a teenaged girl sent to a camp to “cure” her lesbianism. And I’m not trying to devalue the movie, which did a lot of work as far as portrayals of queer characters. But it’s something I’ve been considering–our reflexive tendency as artists to want to sublimate trauma into humor, to repress tragedy until it becomes comedy because it might feel safer. And your TedxBG talk on your experience at Love in Action was very funny, it had a lot of dry humor. Would you say there are different kinds of power, different stakes even, in these different sorts of portrayals?

It’s funny you mention But I’m A Cheerleader! because this was a movie that deeply affected me. If I remember correctly, my first boyfriend (Caleb in the book) introduced me to the movie about a year after I’d been out of “ex-gay” therapy, and I remember feeling thrilled that such an experience was being portrayed and also a little angered that they’d gotten the details wrong. I experienced the same anger when I watched an SNL clip on the subject with Ben Affleck acting super campy. And of course part of the anger I felt stemmed from the fact that these pieces of art were funny, but for some reason unknown to me at the time (denial!) I was locked out of that humor. Many acquaintances who have heard about my book laugh out loud or ask me if it’s a funny book, as if this is a natural element of the memoir genre or the “ex-gay” narrative in general. And while I don’t deny the cathartic effect of humor on traumatic experiences, I find first assumptions to be an uninteresting literary pursuit. I want to startle people out of what they have heard or seen thus far regarding reparative therapy. This is, after all, a movement that resulted in countless teen suicides. This is the movement that killed trans teen Leelah Alcorn.This is the movement that almost destroyed my family and sent me into extreme suicidal ideation. It seems to me that approaching reparative therapy from this tragic perspective (a truthful perspective according to my life) makes for much more interesting and enduring literature.

My TEDxBG talk turned out so differently than how I’d planned it! The minute I heard the audience’s laughter, I knew I had two choices: either 1) chastise them with a silent stare, or 2) lean into the humor. As a high school lit teacher, this is not an unfamiliar situation. Most of my students are much more comfortable when class discussions are infused with a heaping dose of irony. I imagine this won’t be the last time I also retreat into the comforts of humor/irony/coldness/etc. I don’t see this as a problem. If the tone of an article or a TEDx talk helps people to actually pick up my book, I will consider the efforts to have been a success. There is a place for humor, and I believe that place, for me (and perhaps only because of this book), is in the marketplace.

While Boy Erased ultimately did not wind up being a sprawling family drama, it’s true that family really is at the heart of this memoir in a complicated way. Were you aware that your family would factor in so strongly when you set out to write this book?

I set out to write about John Smid, the director of the “ex-gay” facility I attended. I wanted to understand why a human being would subject another human being to so much pain. However, in one of my first nonfiction writing workshops, after submitting a short piece of what would eventually become the first chapter of Boy Erased, my classmates kept wanting to know more about my family.

So I wrote about my father in what would eventually become the second chapter of my book. My classmates were floored. “How can I love and hate this man so much?” someone said during the workshop. I was so floored by that question. “WELL OF COURSE YOU CAN,” my mind was screaming. “That’s what family is all about!” Then, when my book sold on proposal (only 100 pages) to Riverhead, my mother drove to North Carolina to help me move out of my apartment and also to celebrate my book and also the United States of America’s Independence, July 4. We sat on top of a beautiful building in Savannah and watched the fireworks and a woman asked me what I was writing (I had an ARC of another book and also my notebook open), and I was so excited about my book selling and this being a suddenly different country where a book like mine could sell that I just went ahead and told the woman. “What kind of parent would do that to a child?!” the woman screamed, not realizing that my mother was sitting beside me. My mother being who she is, a highly sensitive and kind woman, began to cry a little, and I had one of those ridiculous epiphanies on that rooftop that no one believes exists anymore, and I thought, This is her story, too. The story won’t make sense if it is not also the story of a woman who “did this to her child.” Out of Love. Out of Fear. Out of a South that spends a lot of time killing its children on accident. And of course it doesn’t hurt that I teach “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” every year now.

I think that’s the thing about this book, though. The message, if you will, feels something like: there is so much to be lost when we don’t really look the complexity of things, at these false dichotomies. Particularly as it relates to the characterization of your father, who is an incredibly complex figure in this memoir, his portrayal feels like a huge balancing act. What was important to you when it came to writing about him

My father was one of the easiest characters to write in the book, which was very surprising even as the writing was flowing. I was very worried that I wouldn’t get his life right, but I also knew that there was a lot of power buried beneath the memories I associated with him. As you can probably see in the book, he is truly larger-than-life. Cotton gin owner turned car salesman turned preacher, all of these “businesses” very successful at different moments in his life. People around us always looked up to him. With a figure like this, you have to be careful to balance both public and private personas … and in that careful “balancing act,” I discovered my themes of nuance, particularity, humaneness. This discovery gave new life to my writing, and it gave me a frame for the book as a whole. Will I or won’t I be OK with my father? The answer didn’t come until I’d finally told him a bit about the book. And it’s actually still coming. That’s the nature of revelation, or at least a proper revelation. (Can I talk about Flannery O’Connor yet?)

I discovered that this celebration of nuance was what I was also doing when I tried to reclaim my own narrative. I wanted readers to see that I was guilty of hiding away my “true self” as well. And this process of erasure is something the culture at large has tried to do to both LGBTQ lives and to the lives of disadvantaged Southerners. In that way I was following Flannery O’Connor’s lead (there she is!), by showing people the “grotesqueness” that lives inside all of us (admittedly to wildly varying degrees).

I suppose mentioning this is more or less a spoiler, but you are an LGBTQ activist in Sofia, Bulgaria, where you live and teach. Writing itself is activist by nature; I feel like portrayals of suffering often involve having people’s means of writing being taken away or having their accounts destroyed. The moment when the pages from your Moleskine were torn out was a very powerful moment of silencing. Do you have any visions for Boy Erased from an activism perspective?

I’ve just been invited to speak at a Presbyterian church near Seattle, and I can think of nothing better for this book and its message. Initially, I was wary of speaking to congregations for fear that they wouldn’t like my politics, but now I can begin to see how this message is meant for the church, too. Of course I want people to admire my sentences and my book’s structure, but I really want to reach audiences that might be on the fence about LGBTQ issues (or at least people who have relatives that might be on the fence). I just love living in that in-between space. I like the hard struggle of being between audiences. For example, my mother reads the first few pages of my book so very differently than other people do. I wanted the book to be a little sly in this way, and I suppose my activism has a heritage of “passing” in order to get my message across and be heard before I can become fully visible. A lot of people disagree with this method because it’s coming from a place of privilege (white male potentially straight-looking privilege). I’m very good at hiding. But I don’t know how else to live. When I go home, I don’t hide the fact that I’m gay, but I certainly don’t talk about it much. When I’m out with my Bulgarian boyfriend in the city streets that are anything but tolerant, I usually don’t hold his hand. I tell my students I’m gay, but I don’t talk about gay issues in the classroom very often. I would very much love to find a method of being heard that doesn’t involve hiding a little. Being gay, for me, is always a process of becoming, as I suppose all human life should be.

Can you tell us what you’re up to now? (Basking in the glow of this book being finished certainly counts!)

I’m writing essays to be released around the book’s release date. The essays are a little lighter and/or more simplistic. It’s actually a relief! I’m working on a novel that’s erratic and messy and at times really pretty, though I don’t know what to do with any of these pages yet. Sometimes I wish someone would just tell me what to write next! Televangelist’s wife gone wacky? Jonestown Massacre II? A Walmart being built in a nature preserve with a bunch of hippies? Any ideas are welcomed.

Thank you so much for your time, Garrard. I think we’ve reached the end of this interview. Unless this is the time you’d like to talk about Flannery O’Connor.

Haha. I’m obsessed. I’ll just end up sounding like a babbling fangirl!

*

Boy Erased is forthcoming from Riverhead (Penguin) in May 2016. It can be preordered here.