Add it to the quirky mysteries of life: along with how one of the most famous creative writing programs happens to be founded here in a city bounded by nothing much but cornfields and rolling hills, that every four years Iowans become the most important citizens in the U.S., the first to choose the next leader of the free world. And then picture me: an Asian-American, whose votes in California used to amount to nothing more than a symbol and a duty, about to caucus for the first time, holding one of the golden tickets as an undecided voter.

We’re seated inside a packed auditorium, waiting, the designated start time having come and gone, but we’re told people are still signing up to get in. “It’s mayhem out there,” says a newcomer, finding a seat behind me. Volunteers hurriedly fill the empty aisles with folding chairs. I begin to worry about the fire code. Seems they take elections here seriously, even more than any contingencies for emergency.

On the proscenium, Hillary Clinton smiles forcefully at me—or her life-size cardboard cutout, promising to fight for us. Bernie Sanders is everywhere, too, in his posters asking us to believe in the future. His supporters don many creative tee-shirts, one of which wants me to “Feel the Bern.” Along the wall, a banner with his name stretches out big enough to enshroud two or three corpses—very convenient, in case the burn gets out of hand or the exits get blocked from overcapacity.

On the proscenium, Hillary Clinton smiles forcefully at me—or her life-size cardboard cutout, promising to fight for us. Bernie Sanders is everywhere, too, in his posters asking us to believe in the future. His supporters don many creative tee-shirts, one of which wants me to “Feel the Bern.” Along the wall, a banner with his name stretches out big enough to enshroud two or three corpses—very convenient, in case the burn gets out of hand or the exits get blocked from overcapacity.

Martin O’Malley is almost nowhere, his slogans absent, but one can assume it’s something to the effect of “Gunning for Vice.”

Auditorium. Proscenium. The very words conjure the world’s first democracy. I picture myself amid Athenians squabbling over issues before casting our pebbles into an urn. It’s a messy process, with Socrates, I imagine, pestering us with endless questions. But how privileged I feel, able to take part in a modern reproduction. Every four years, and I happen to be at the right place and the right time, my first experience and probably my last, of a charmingly antiquated version of politics in action.

A few months earlier, I’ve missed all the chances to rub elbows with the candidates. “Hillary just walked past my window, NBD,” a friend posted on Facebook. “Anybody wants to go see Bernie at the Field House?” was the refrain just a few weeks ago. I myself had asked some of my friends, “Who wants to come see Bill with me?” I was, of course, referring to the former president, but the title’s passé. What we quickly learn here, with slight smugness and a belated grasp at the obvious, is that these famous personages are humans, too—why not call them by their first names? Even their very presence becomes passé. I ended up deciding I couldn’t be bothered to walk ten minutes to the Sheraton where Bill was to hold his talk. “Feeling lazy,” I texted.

Half an hour into the proceedings, the precinct captain asks if people would be willing to move to an overflow room. He’s miscalculated the request, as soon, there are too many extra chairs; he tries to reverse course. “If you’re a supporter of the Secretary,” he says, “there are many empty seats on her side—” to which the Bernie supporters quickly latch on, hooting, clapping, before being interrupted—“No, no, no, they’ve been kind enough to move to the other room.”

Half an hour into the proceedings, the precinct captain asks if people would be willing to move to an overflow room. He’s miscalculated the request, as soon, there are too many extra chairs; he tries to reverse course. “If you’re a supporter of the Secretary,” he says, “there are many empty seats on her side—” to which the Bernie supporters quickly latch on, hooting, clapping, before being interrupted—“No, no, no, they’ve been kind enough to move to the other room.”

To kill time while an attendance tally is taken, the precinct captain hands the microphone to volunteers willing to sing. I remember “This Land Is Your Land,” the Iowa Fight Song, and some patriotic number rendered by an overenthusiastic O’Malley fan. I see more creative Bernie tee-shirts: “Backed by the people, not by the banks” on tie-dye; another declares, “Bernie Fucking Sanders 2016.” “These kids are the cutting edge,” I hear someone say.

Around eight o’clock, we finally have a tally: there are 759 people in the precinct, up sharply from four years ago when there were about 500. I feel the excitement as the crowd bursts into cheers of self-congratulation.

“Normally,” says the precinct captain, “we take thirty minutes for realignment.” Meaning that on the first round, voters get to move and pick their camps. The candidate who doesn’t get enough votes gets disbanded, and his or her supporters have another half hour to realign themselves. “But I think you’ll kill me if I enforce this one.” Laughter, and a motion quickly passes to adopt a shorter process.

Then comes the moment I’ve been waiting for: to hear from the different camps in their attempts to “sell” me their candidates. I perk up from my seat, notebook in hand. “Two minutes each,” says the precinct captain. I’m dismayed. We’ve spent much longer singing silly songs and cracking jokes; now, the actual meat and potatoes of the caucus takes less time than for me to go sit in the toilet.

“Who among you are still undecided?” he asks, after the tepid campaign ads concluded. I’m about to raise my hand, but seeing that there are only one or two others, and assessing that the mob—hungry and mostly un-dinnered—has already made up its mind, I retract my hand and pretend I have an itch behind my ear. The sole brave undecided woman (the other has disappeared as well) marches into the O’Malley camp to consult. All in vain, for not a minute passes when that faction is declared non-viable and its supporters walk away with tails between their legs.

I scramble to decide who I’m for—trying to remember the snippets of debates I’ve seen and the commentaries. But here in this room, I find myself mulling over a different set of factors:

Most of Sanders’ supporters are overwhelmingly young students—don’t I belong there? I even see some of my classmates. And look at the stickers they’re wearing—matte with an elegant simplicity, a single “Bernie” on blue, red, and white colors that are slightly muted: very vintage, very chic. The Clinton supporters look a lot older—the stickers they wear have a deep, glossy blue that reminds me of computer packaging—PC of course, not Mac. One of their team captains, wearing a baggy sweater, keeps walking along the aisle, annoying everyone by repeating, “Thank you for waiting, we love you.” But then I see a cute, young couple holding hands in that camp, and I overhear someone saying she’s a professor of physics and astrophysics, and I think perhaps it’s not such a bad group to belong to.

On my way home that night, I wonder if the secret ballot is better than what I’ve just experienced. Do I prefer the Jeffersonian model of an equanimous mind making decisions, and in the Emersonian belief that selfhood is sacred, that the enlightened minority often get things right? Or do I believe in the Hamiltonian model that there is truth in collective wisdom, that I should be swayed by it, as evidenced nowadays by the general accuracy of the Ask the Audience Lifeline in Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

Maybe my expectations of the caucus were set too high. I expected a kind of parliamentary debate among my peers. What I got instead was a contest in optics, of adolescent peer pressure, of not so much voting for who I believed in, but of voting among who I think I should, who I think I’d look good with.

Or perhaps that is the nature of elections, and indeed, the very nature of human beings. That given all the facts and cost-benefits, few of us would deny our intuition for a rational judgment that somehow feels wrong–and such intuition is often formed from the first time we see people or hear them speak. That in the end, we often go with gut feelings, and only find the justifications later.

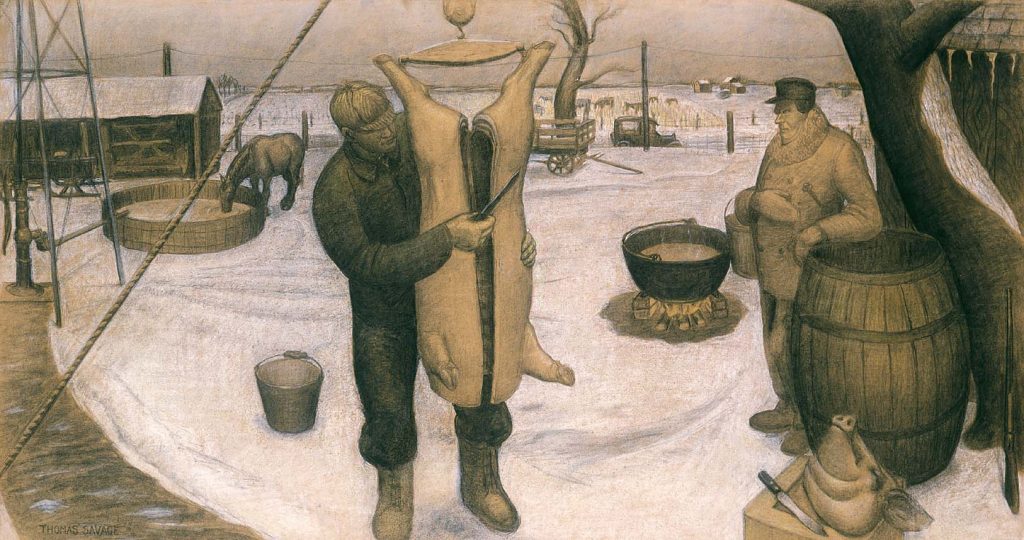

Image: Savage, Thomas Michael. “Butchering in Iowa.” 1933. Charcoal, crayon, and pencil on paper mounted on fiberboard. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.