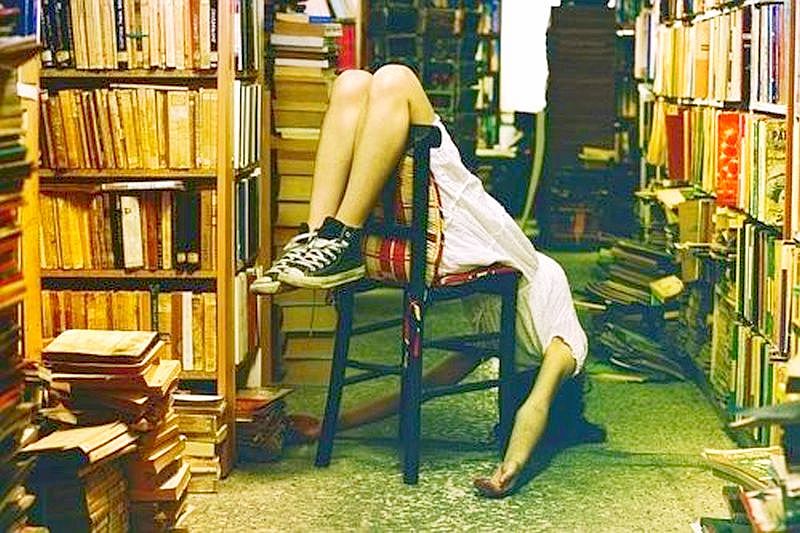

I can’t read just one book. As any avid reader will recognize, my apartment is littered with half-read books: books with scrap paper sticking out of the middle, books with spines cracked open as librarians always tell you not to do, books dog-eared, and even books stuffed into other books to mark two pages simultaneously. I leave a paper trail behind me wherever I take shelter.

This scattershot reading style has been with me since I was a kid, back when I would borrow a stack of books from the library and have to finish them all within two weeks, because renewing books was for the weak. But now, I can buy my books; the books I do borrow don’t need to be returned for months. Now, I am drowning in my books, and each novel I bail out is quickly replaced by two more. With no encroaching deadline, no limit to how many new books I can take home with me, I have begun to finish less and start more. All these books, so randomly selected, create a cacophony in my head, as each sings out its charms to catch my attention. Inevitably, one of these half-read books gets lost in the shuffle. With the ones I don’t entirely neglect, I have a harder and harder time picking up where I left off.

To end this cycle without limiting myself to just one book at a time, I am attempting to curate the books that litter my home. I’m trying to cluster books together, to avoid, as best I can, the erasure of what I have read by what I am now reading. Memory instantly improves if you build a network of relations surrounding the remembered object, my theory being that the more I categorize a group of books together, the easier it will be to remember them all. And the categories, rather than being static, are constantly shifting. Certain books, I am finding, harmonize better than others. Certain books, when read together, satisfy all my literary cravings. Certain books start a conversation, one that teaches me how to read, think, and write better.

For some books, a cluster forms from a question. For example, after a student sent me a collection of David Foster Wallace’s nonfiction, I finally buckled down and read the eponymous essay, “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again.” Never a big fan, I was; however, immediately struck by how Wallace’s voice felt attached to a body, that reading him was exactly like having a conversation with the author, instead of the inauthentic, but stylish voice of other “voice-y” writers. I wondered if that was how Wallace really sounded, or if he had constructed a perfect persona, as consistent as a human personality. So when I picked up another book, to take a small break, instead of grabbing whatever I saw first, I built my cluster. I started reading D.T. Max’s biography on DFW, Every Love Story is a Ghost Story. When my mind wandered from these texts, I decided I wanted to hear from real lovers of Wallace’s writing. I picked up Zadie Smith’s Changing My Mind again, and reread her adoring essay on his work. To hear from real lovers of Wallace, I bought Mary Karr’s memoir Lit. This is not a formula. I’m not recommending that one should read about the author to better understand the literature. It is just that in the case of my reading Wallace’s essays, I decided to follow the biggest question in my head, and the biggest question in my head, in this example, was, “Who is this guy? And is this what he’s really like?” Once followed, the cluster practically built itself.

Some books I cluster by theme. I read Edmund White’s memoir Inside a Pearl and Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce practically side-by-side, both about Americans living in France, and it was like listening to two people gossip intelligently about Paris and Parisians, at times agreeing in their cultural insights, at times filling in what the other had not spotted.

Some books, by recommendation. Before I started reading Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, I heard two friends discussing the novel, and one of them mentioned Mary McCarthy’s The Group as a better portrait of longstanding group friendship. I immediately got both books, and indeed, though each one was lauded for its portrayal of friendship and epic time span, the novels were completely separate in their preoccupations.

And finally, some books are clustered by sheer accident. I picked up Jennifer duBois’s Cartwheel after attending a recent reading, intending to read it on its own. I happened still to be reading The Group, and saw how both books were interested in the perception of truth, and explored this idea with rotating third person, so that one character’s telling of an incident is often contradicted or complicated by another’s. Reading them together showed me how sometimes, many half-right perspectives create a total confusion of truth; and sometimes, many half-wrongs pieced together form a strikingly accurate picture.

All of this to say that clustered reading is a handy way of having your books and reading them too. And that even the most temperature-controlled, tightly curated clusters leave room for happy accidents. Most books, if not all, have a way of speaking to one another—if you’re willing to start the conversation, they’re happy to do the rest.