“Think about the opportunity costs,” my brother told me, “in getting an MFA.”

We were on the phone: he in his Midtown Manhattan bachelor’s pad; I, in a 1930s-era split student housing in the Midwest. To put it into context, this was going to be my second MFA in creative writing—many would’ve thought one to be enough, if not crazy enough. It’s not an education that, to borrow another term of his, has good ROI. My brother has that other kind of degree acoustically close but fundamentally (and most often than not, aggressively) opposite: an MBA.

“Don’t just think about the stipend you’re being offered,” he continued. “Think about the amount you’ll miss out by not being back in the workforce.”

To put it into context: I am not financially inept; I have student loans, yes, but no credit card balances; I live frugally, cook my own food, limit my spending; I’m not one afraid to use coupons or to patiently wait for markdowns; I’ve previously saved up money from working as a paralegal at a Big Four accounting firm. To put it into context: I’m a responsible adult—or at least that’s what I’d like to think.

Several months into my new MFA program, and pondering on my longer-term plan, the question of what it takes to survive as a writer is heavy on my mind again. What are the economics involved in being a writer?

Virginia Woolf famously wrote that writers need to have a room of their own and five hundred pounds a year in order to create. She was referring to women writers in particular, lamenting their lack of publication (or alleged quality of). She wrote her essays around 1928, and towards this fact, much has been done to come up with a contemporary number. Susan Gubar, in a 2005 introduction to A Room of One’s Own, pegged the amount at $37,000. Accounting for inflation, that would be something like $45,000 in today’s currency, just shy of the U.S. Census Bureau’s median salary of $52,000.

Virginia Woolf famously wrote that writers need to have a room of their own and five hundred pounds a year in order to create. She was referring to women writers in particular, lamenting their lack of publication (or alleged quality of). She wrote her essays around 1928, and towards this fact, much has been done to come up with a contemporary number. Susan Gubar, in a 2005 introduction to A Room of One’s Own, pegged the amount at $37,000. Accounting for inflation, that would be something like $45,000 in today’s currency, just shy of the U.S. Census Bureau’s median salary of $52,000.

Woolf, of course, was born into an affluent and influential family, and herself inherited a sizable sum (£2,500) from a deceased aunt. Some of the criticisms about her statement above stemmed from this: that she’s speaking from a position of bourgeoisie privilege. She admitted to worrying that readers might think she’d made “too much of the importance of material things” into her analysis on writing.

But I find her argument—linking intellectual freedom and economic freedom—to be convincing on the whole. An urgent and practical concern for most of us, even: how can I find the time to write a novel if I can’t even pay rent?

One of the obvious answers, for me, is to pay lower rent, so that the $45,000 that Woolf recommends is likely smaller—much, much smaller. In Iowa City, I’m surviving on less than $20,000 per school year. Being a grad student, my health insurance, counseling services, and gym access are mostly covered—three things that maintain my physical and mental well-being. For the first time, I have my own studio in which to read and write; I have more free time than if I’m working eight-to-five every day.

“But what about retirement?” my brother asked. “You’re not that young anymore.”

This was true, and to be responsible, something I needed to think about. According to Fidelity’s guidepost, in order for compound interest to work in my favor, I needed to have saved up the equivalent of my current yearly salary by the time I turned 35. My grad student income is too low and impractical to use as a benchmark—so let’s just assume the median U.S. national salary from earlier, in case I move out of Iowa City: $52,000. Without my employer/school offering 401(k) matching, I am clearly not going to reach this, not even with the retirement account I’ve saved up pre-MFA.

I began to panic, to have visions of life at sixty-five: tenement housing maybe; living off canned goods; no heating because I failed to pay the gas bill; showering only occasionally to save on water. I began to think that maybe I should’ve stayed in that cushy paralegal job in the city. I remembered seeing on Facebook that a former coworker of mine had bought a loft in downtown L.A after only two years with the firm. “Homeowners!” the picture had said.

Why is it so difficult to cobble up a good life as a writer? Why can’t I graduate with an MFA and instantly be hounded by headhunters, each of them competing for my contract, offering sign-on bonuses? For the sake of argument, let’s assume that I’m a capable enough fiction writer—why can’t I make as much money as, say, a capable mechanic, paralegal, doctor, or financial advisor?

“Money dignifies what is frivolous if unpaid for,” wrote Woolf. If the world indeed valued literature and demonstrated it monetarily, we likely wouldn’t be talking about the need to have a room and five hundred quid a year. It would be obvious.

But the difficult economics in sustaining a writer’s life also leads me to think more seriously about this path, and not coincidentally, about life itself. Without mystifying poverty—for I am not against being compensated—the truth is, capitalism excels in pricing goods but not much else. An extension to Woolf’s quote: Money, in fact, makes frivolous the most essential things in life.

Many times while I worked as a paralegal, I’d tell people that the busier I am, the better, because time passes by quickly. Before you know it, the day’s over, and then, the whole week. This is such a persistent—and accepted—ideology, that more people would raise an eyebrow if you tell them you’re not going to work simply because you don’t feel like it. It’s sad to know that our existences could be traded so cheaply for a sum, that many would willingly become automatons and let life numbly pass them by.

Here’s a possibility: as writers, we have more of the one truly non-renewable resource in the world—time. And I’m not just talking about quantitative, chronological time. When we sit down in solitude and think about life, we extend life. When we read about the different permutations in which lives have been led, or when we contemplate life in our own writing—time is stretched, warped, mutated, created anew.

I think about Henry David Thoreau and his cabin in the woods—though few of us can closely replicate his experience (tiny homes, perhaps, are a contemporary reincarnation), Walden surprises us by showing how few material things we really need to live, to thrive:

“In accumulating property for ourselves or our posterity, in founding a family or a state, or acquiring fame even, we are mortal; but in dealing with truth we are immortal.… That time which we really improve, or which is improvable, is neither past, present, nor future.”

“In accumulating property for ourselves or our posterity, in founding a family or a state, or acquiring fame even, we are mortal; but in dealing with truth we are immortal.… That time which we really improve, or which is improvable, is neither past, present, nor future.”

Why haven’t more of us asked: have you considered the opportunity costs in going back to the workforce? In living a cushy but unexamined life?

I’m not dismissing the idea of being financially responsible, of having to work for pay, of saving up for retirement. But I’m also not willing to easily surrender to conventional notions of how time is better spent and how much I need to make. I’ll have to keep finding my own room to write, or perhaps, a cabin–be that in the form of a residency, a fellowship, a second MFA, or by living cheaply abroad. I’d like to think that I’d have lived my life in such a way that by the time I reach sixty-five, there’d be no real need to retire.

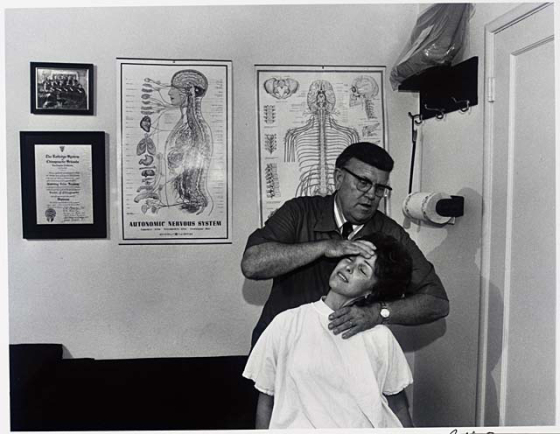

Image: Owens, Bill. “Working: I do it for the money.” 1978. Gelatin-silver print photograph. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles.