It’s no longer taboo to admit, as an American Jew, that you have a Christmas tree. Some people call it a Hanukkah bush, which is about as absurd as someone diplomatically wishing you “happy holidays” after the eighth day of Hanukkah. It’s a Christmas tree, and some Jews, whose religious services, as a friend pointed out, will never be broadcast on the local news, long ago decided they wanted in on the holiday cheer, and that there’s no shame in that.

I grew up with a Christmas tree, a mostly neutral totem of my mother’s non-Jewishness. While she was never religious, and even leaned toward agnosticism, the tree was a reminder that she did not wish even her secularism to be absorbed in the admittedly lukewarm winds of Reform Judaism. As my brother and I grew up, it also began to serve as an insistence that Christmas was American. If we were American Jews, with the American part italicized, then a Christmas tree was not a religious symbol, but a nod to the country that allowed us to be the kinds of Jews we were, the plain frame around our difference. Like our whiteness, I’d venture now, it was part of what made our variation from the norm acceptable.

Because the Jewish calendar is lunar, some years my family celebrated Hanukkah weeks before the tree went up, and others we would rush from lighting the menorah in one room to another where we would palm our Christmas stockings and hang ornaments from the tree. It wasn’t until I was fourteen or so and began to plumb my Judaism below the Reform movement’s then-ceremonial surface that this duality began to feel extravagant to me, and not until I was in college that it felt disingenuous.

But the roots of my discomfort extended further. Once when I was about ten and my mother’s mother was visiting, she sat before our tree on Christmas Eve and began to sing a carol. I had never known my grandmother to be religious, although apparently she had wanted me baptized, but the honesty of the religious feeling in her voice bewildered me. The music had upset the neutrality of the Christmas symbol in our house, the idea that it was just part of our hyphenated identity, symbolic more of our parents’ union than of any broader movement. At the same time, it underscored the poverty of our Christmas ritual, suggested that the holiday involved more feeling and meaning than we had ever experienced. I didn’t know yet to ask my grandmother about her own faith or rituals, to try to understand what was missing for her in a situation where a tree was the only token of what had been a constant in her life.

Sometime in college, my brother and I began openly resisting the Christmas in our house: we were Jewish, we told my mother, and we didn’t need more presents. After our parents moved from Pittsburgh to California, we stopped going home for the holiday, preferring to visit at Passover and Thanksgiving. Occasionally my husband and I visit his parents over Christmas, where his mother, who converted to Judaism, routinely has a Hanukkah party sometime around December 23, regardless of the Jewish calendar. When I ask him if he thinks his mother misses Christmas, he says no.

In California, my mother and father have begun spending Christmas in a place where my mother vacationed as a child. “This feels like my place,” she tells me over the phone, and so I’ve come to understand the Christmases of my childhood the same way: as my mother’s place, a way of showing her children, who she knew might not grow up to observe her traditions, where she came from. This year, when we discussed her plans for Christmas, she suddenly said, “You know, I realized it’s not really your holiday.” Yes, I said, and I could feel us both breathe into the moment: here we were, two adults with two different ways.

On Christmas Day this year, my husband and I went to the movies–the theater was packed–and then to Shabbat dinner at the home of some new friends, where we pounded the table and sang into the night. The hosts had rushed home from a family Christmas party; one guest animated the dinner conversation by asking us if we had ever been tempted by the merciful qualities of a New Testament God. This is what I had been missing: the opportunity, on a holiday America believed belonged to everybody, to be among only Jews, to harmonize our own observance with that of the outside world, to inflect America’s default Christianity with our Jewishness, even if we could not, like our more religious brothers and sisters, quite ignore it.

At thirty, I text my mother “merry Christmas” and play Jessye Norman singing hymns. I send my family presents that might not arrive before New Year’s. My understanding of my mother’s Christmas tree now includes thankfulness for a teaching it included: that the frame of the majority never quite goes away. It’s always in the streets, in your house, in your heart. When my husband and I finally took an Uber home from dinner, we shared it with a couple of college-aged boys and the driver, who had hung a small homemade Yemeni flag from the rearview mirror. He had been driving since 4 pm, he said, and didn’t volunteer whether he had observed the holiday or not. J. got in the back seat. The two young men asked him how his Christmas had been so far. In his pause before responding, I heard him, like the driver, make the decision not to announce himself. “Just fine,” he said. “We haven’t done too much of anything today.”

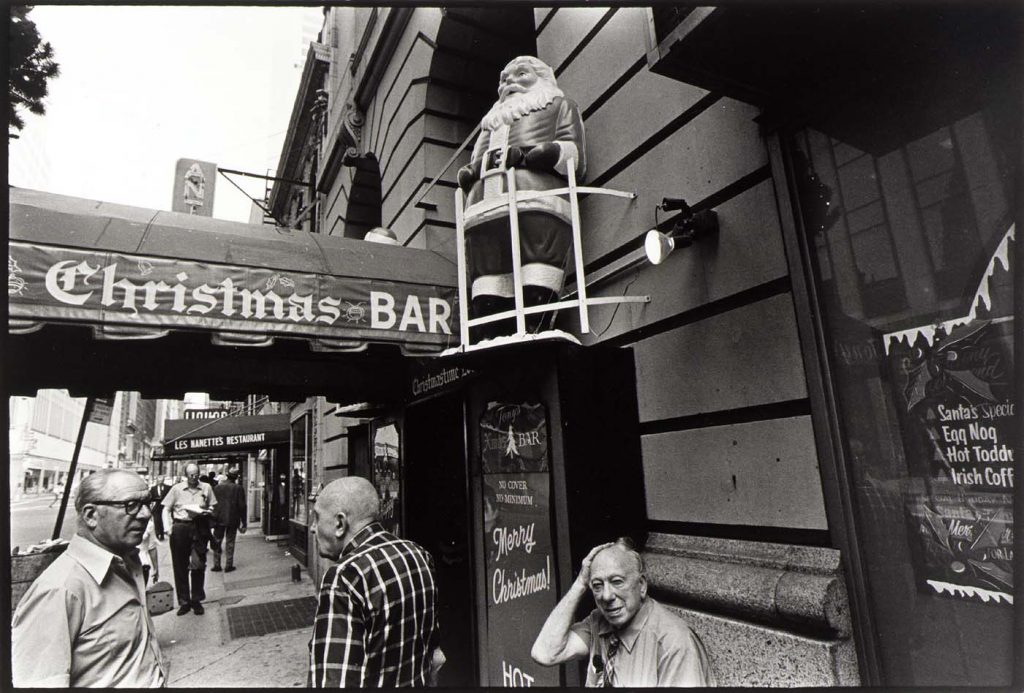

Image: D’Alessandro, Robert. “The Christmas Bar.” 1974. Gelatin silver print. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.