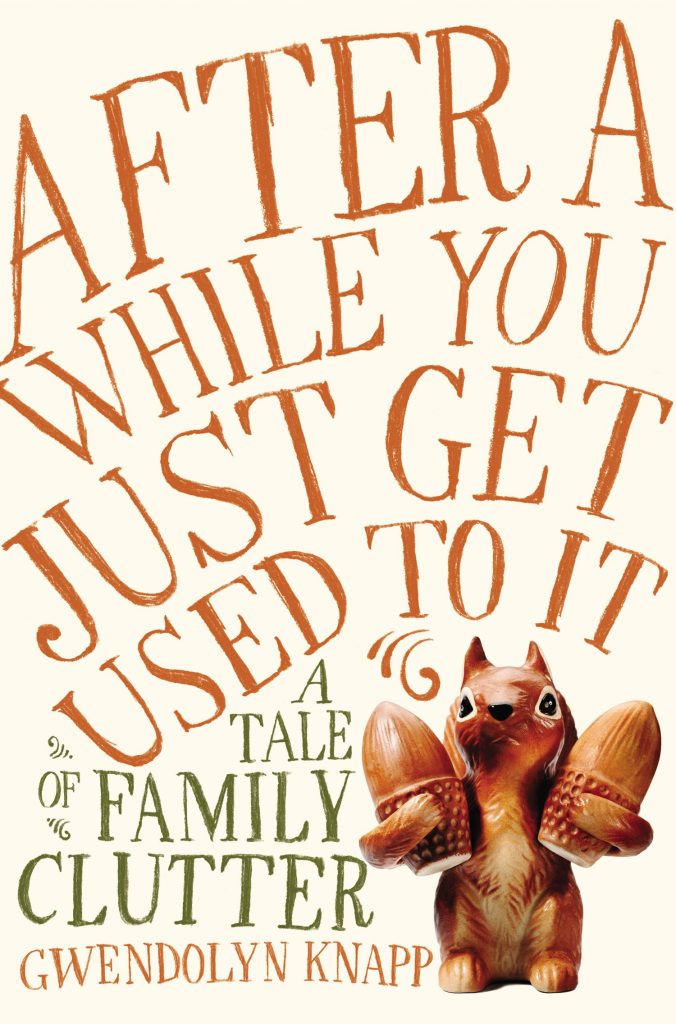

In recent years, much has been made of hoarders—in the wake of the eponymous hit A&E show, popular media has been fascinated with those suffering from pathological overconsumption. But in Gwendolyn Knapp’s hilarious debut memoir, a collection of novelistic vignettes about growing up in a junk-filled house in redneck Florida within a family of “eccentric crackers,” and afterward carving out a life in New Orleans, only to have her mother Margie pack up her copious baggage and follow her daughter to the Big Easy, the hoarding is atmospheric—it never takes center stage. It doesn’t overshadow Knapp’s wonderful stories about family feuds, failed relationships, and inane jobs. Knapp, for instance, works at a cocktail convention and a cheese shop and has a food column, despite her lifelong battle with IBS, and her sister becomes a goth after getting a job at a fast-food joint. Rather, it’s a fast-paced book about, to some extent at least, the junk that makes us who we are.

The humor here is as wacky and multi-layered as the crap that takes over Knapp’s childhood home—think hair-care items ordered from infomercials, stacks of the Utne Reader and lightly damaged CD cases. Knapp’s sense of humor, however, is of the gallows variety—she doesn’t sugarcoat the pain of her oxycontin addict aunt’s eventual death, the struggles of growing up poor, the family fights that teeter between hilarity and violence, nor the anguish that comes with dating a serial cheater.

In After a While You Just Get Used to It (Penguin Random House, 2015), the hilarious meets the heartbreaking. Readers come to know a dive bar palm reader who calls herself the Disco Queen Taiwan; a slumlord with a penis-of-the-day listserv; and Betty, the middle-aged cocktail convention volunteer who soils her pants on a party bus and is dealt with in the worst possible way. Throughout it all, Knapp’s honesty is a force as strong and compelling as her rollicking wit, bawdy jokes, and knack for assembling pages-long parades of the most zany and entertaining metaphors I can recall encountering.

Knapp, a sixth-generation Floridian, now resides in New Orleans, where she serves as the editor of Eater NOLA, and as a freelance food writer. The very entertaining author recently spoke with me about place-based writing, the art of balancing the heavy and the funny, and how comedy tends to translate to the page. Oh, and we also talked cheese.

*

There’s a definite flow to this book, but the chapters themselves stand on their own quite well. Did you write them as personal essays first, or did you plan on penning a memoir all along?

I did not originally set out to write a long-form piece. Earlier versions of some of these essays had already been published on their own, and some other published essays about my life didn’t make it into the book. But it quickly became evident that publishers weren’t particularly interested in essay collections, so I had to find some sort of an arc in there.

Many seem to be proclaiming you as a true “Southern gothic” writer. How do you feel about this classification?

I do like that people read my writing as Southern and not just as that of a bland white person [laughs]. But I feel like if you are a writer who’s Southern, your sensibilities should probably just be organic. I grew up poor in Florida—I have a very specific sort of family—and the characters in those stories are deeply embedded in my story, and in who I am. I feel like Southerners deal with different situations and circumstances than people in other parts of the world—we have such distinct issues with poverty and social issues that don’t get addressed because you’re dealing with crazy belief systems. The Southern canon seems to be ever-changing as the South itself evolves, so I know my writing doesn’t necessarily hark back to the days of Flannery. But Southern writing is nuanced—I mean, the Florida Karen Russell writes about is vastly different from my Florida, even though both have elements of a clearly bizarre place. It’s a place of decay, and where a lot has gone very badly, but a place I love all the same. I’m very comfortable writing about Florida, but I have a harder time with New Orleans. I would never attempt to tell you, “This is what New Orleans is like!” A lot of writers, especially post-Katrina, try to speak like an authority about it, but I would never feel comfortable doing that. Nola is a weird place like that—you don’t wanna exert ownership if you’ve only been here for eight years, like me. Southerners don’t take kindly to that—you kinda have to have this almighty reverence for the place [laughs]. I feel like I can write about Florida with irreverence, but have to write about New Orleans with reverence.

You have an MFA in fiction, and you’ve published several short stories. What was it like, branching over into the nonfiction realm?

When I was in grad school, my grandma had just passed away, and my mom was starting to act like a real nut, and I was trying to work on this godforsaken novel. So I started writing some nonfiction, and really just got into it. It was refreshing to be able to study essay-writing and to be like, “Oh, I feel like I could write this sort of thing, and I also want to,” and so I did. I published fiction first, but then right around the same time, I started publishing fiction. When I graduated, I was still working on this novel that will never see the light of day, but I was probably writing more nonfiction.

What type of nonfiction were you reading/finding inspiration in?

Let’s see, in terms of inspiration, Jo Ann Beard’s Boys of My Youth was really definitive. Joan Didion is big for me, too, even though I feel like I have nothing in common with her. I also read a lot of Truman Capote, Erik Larson, and David Foster Wallace, even though no one else can get away with DFW’s style of rambling on and on. Lately, I’m reading a lot of the new wave of female essayists who are sorta killing it—Eula Bill and Leslie Jamison and Roxane Gay and Rebecca Solnit. It’s all great, but I still feel like my style is a lot more aligned with David Sedaris and Jenny Lawson. However, I don’t limit myself to reading that kinda stuff.

You handle humor so well, I’m curious about the types of comedy that inspire you.

I’m a big fan of comedy. I grew up glued to the TV, always getting lost in SNL reruns. Carol Burnett and Tracey Ullman were both, well, I don’t want to say inspirational because that sounds cheesy, but certainly definitive. I also grew up watching a lot of Roseanne, and I’m in awe of the writing on Arrested Development. So, I do like comedy. But not all of it—I think a lot of comedic shows and whatnot are kind of overrated, because there’s generally not as much at risk in terms of characters. It’s why I prefer the written word—on movies and V shows, I feel like things have to be watered down and made much lighter or more positive, to be widely appealing. I’ve been watching Aziz Ansari’s Master of None, for instance, which is so great in many ways. But I don’t find it as groundbreaking as everyone seems to think it is—it touches on some new stuff, but it’s yet another show about rich New Yorkers. We’re so obsessed with privilege and calling out everyone’s privilege as far as gender and race are concerned, but classism still never seems to play into things.

Tell me about readers’ reactions to your book.

I don’t think a lot of people are down with the heaviness … some people seem to think it’s really depressing or sad, but that’s life; is it not? But in any case, my mom likes it [laughs].

I have to ask—have any of the exes mentioned in the book read your memoir?

Yes, I know one has because he drunk-texted me two weeks ago, I knew he was gonna read it when it came out, because he’s a huge narcissist [laughs].

What’s next for you, writing-wise?

I’ve been researching a book about cheese, and the tricky thing is to find a way to balance all the information about farmers’ strategies and cattle and specific plans, to not just get bogged down with the mundanity of cheese production. So, I’m hoping to present what I learn in a personal essay-, personal narrative-type way. Reading about cheese is not always entertaining—most of the cheese books out there are so boring! I want to incorporate information that’s not just research-y and technical. For instance, I’m interested in writing about the relationships that dairy farmers have with others in the cheese business. So, I’m working on that, but I’m also working on a novel about door-to-door magazine scammers in Florida. As I’m doing this cheese work, it’s nice to balance it with something that’s more literary, that allows me an escape, an outlet to write about more crazy people [laughs].

So, seeing as your memoir is all about clutter, I’m dying to know—what’s on your writing desk right now?

I have part of my peanut-butter toast, a huge stack of cheese books, a squirrel eraser, some pictures of squirrels, and post-it notes about Eater posts and how to make them more SEO-friendly. I also have my calendar, some squirrel underpants, a Pez bunny, and them some random other crap [laughs]. Maybe I am the face of clutter and craziness.

*

After a While You Just Get Used to It is available through Penguin Random House and Amazon.