My husband and I are yard-sale junkies, like our mothers before us. When we walk in our neighborhood, we rarely pass a cluster of rusty tea-kettles and CD-holders without taking a closer look. In our primes, we were both shameless appropriators of sidewalk goods: in Cambridge, MA, I once carried a plywood bookshelf nearly a mile home. His greatest find: a complete set of nesting screwdrivers. Alas, the great New York bed-bug crisis of 2010, along with our adult wisdom about the protein contents of other people’s futons, has made us wary of taking home anything upholstered.

But we still sift through the one item New Yorkers seem to feel relatively safe about leaving and taking from a sidewalk: books. Everywhere from the Upper East Side to my neighborhood in Brooklyn, I see books laid out on stoops, in front of apartment gates, and in unlikelier places. These collections can serve as a kind of time capsule (Microsoft Office manuals from 1995; textbooks printed in ITC Lubalin Graph), effectively dating for the stranger the last time the discarder cleaned out his crawl space; or they can serve the same function as a line in an online dating profile (dog-eared George Saunders, bookmarked Ann Patchett). I’ve always found something touching in the implicit hope that a passerby might actually want three decades of Architectural Digest, and marveled at the number of copies of A Natural History of the Senses nobody seems to want.

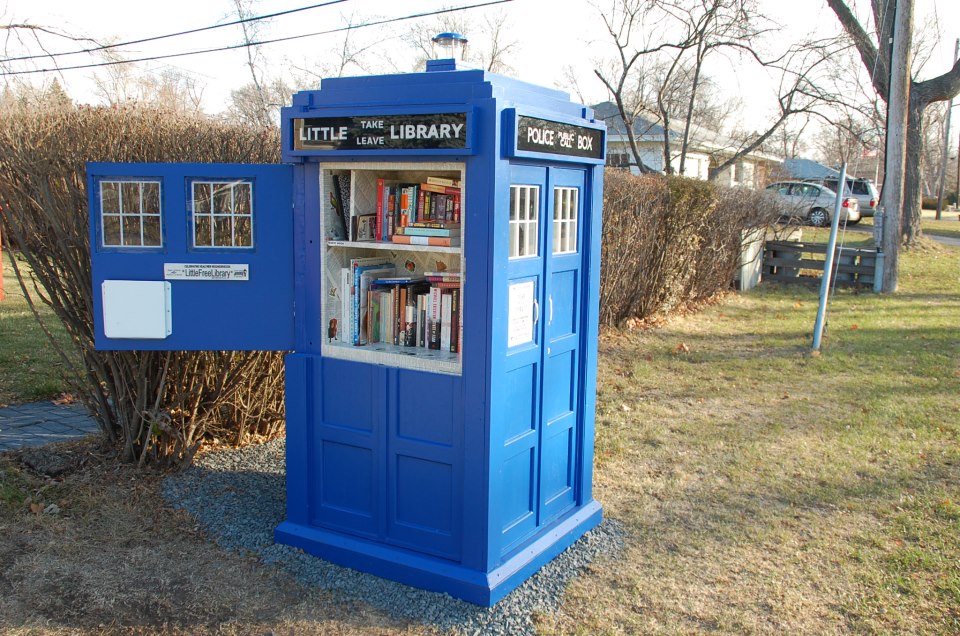

About a year ago, a Little Free Library appeared on our street, on the route that leads from our shoe-repair- and all-night-grocery-store-dotted commercial drag to the quiet residential streets closer to Prospect Park. Little Free Libraries, named for the eponymous nonprofit, are usually wood and plexiglass boxes on stilts, painted or not, intended as a place to “take a book, return a book” and foster “curbside literacy.” If you want to start a library, you can build one yourself (to be in its network, the organization asks for a $40 charter fee) or you can order a “Blue Tobacco Barn” or other prefab style for between $200 and $350.

Since I discovered the little library, I’ve dropped off copies of Eula Biss’s Notes from No Man’s Land and Marilynne Robinson’s Home and snagged Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy and a collection by Tomas Salamun. The other day, on the way home from a run, I stopped by to search for a new novel and was astonished at my haul: I came away with a brand new copy of Laura van den Berg’s Find Me and a battered paperback of Far Tortuga, both of which I’d been wanting to read. Sticking out of Far Tortuga was a phone number scribbled on an orange Post-it. I thought seriously about calling it.

Much as I look forward to passing the painted box on my walks, the freegan in me is a tiny bit skeptical of the L.F.L. and its culture of sanctioned swapping. With its vague civic aspirations (“curbside literacy”) and cute, D.I.Y. aesthetic, it might be easy for some to write off the Little Free Library as yet another calling card of a gentrifying (or already affluent) neighborhood. Who trades good books with strangers? People who read a lot already, can afford to own rather than borrow, and who don’t know their neighbors very well. (It should be noted that in my unscientific survey of other L.F.L.’s, there’s a fair share of dreck as well. Some people only buy books, it seems, when they are at the airport).

To what cultural institution does the L.F.L. really aspire: the public library or the display of books on a stoop with a handwritten ‘free’ sign? And does it offer something additional to either of those institutions? In my neighborhood, the L.F.L. is around the corner from a public library, which itself is across from an elementary school. During all its open hours, the library is full of parents and toddlers making parent and toddler noises, senior citizens reading the New York Post and trying to figure out if they knew each other in high school, and kids doing their homework after school. It’s a public space that has acknowledged that the actual public will take more advantage of it if it relinquishes the library’s traditional claim to studiousness and quiet.

The L.F.L., by contrast, seems boutique, its design likely to serve the interests of people who don’t need its civic mission. Its quality is dependent on donations from people who know about it and are mindful enough not to just dump their toaster manuals, and it’s cared for by a volunteer “steward” in the neighborhood. That means someone has to know about the organization and request to be part of a global, not a local, network. Someone very well might try to tour all the Little Free Libraries in Brooklyn, but it seems unlikely that you’d seek out the stoop books outside your immediate neighborhood. And unlike the public library, the L.F.L. is not a public space–or is it?

Surprisingly, I’ve found, by formalizing–the better word might be condensing–the tradition of discarded stoop books, the little library adds a direction to the conversation that starts when I leave a review copy of a bad Holocaust novel on my doorstep, and that continues, but trails off, when someone (astonishingly) takes it. I never get to ask the person who takes a book I didn’t want why they took it, but now, instead, I get a response in the form of another book that’s sitting there waiting for me. Even if strangers leave and take books independently, the assortment of books can make the box feel like as crowded as a public library during after-school hours. Last week, a handful of Judy Moody-type early reader novels appeared in our L.F.L.–there were the parents and kids making parent and kid noises. I have no doubt that when some grown daughter makes the trek from New Jersey to clean out her aging mother’s apartment, some of those books–old CUNY-issued copies of Canterbury Tales or Tom Clancy novels or Clan of the Cave Bear–will make their way to the L.F.L., and they’ll rub waists with Judy Moody and Jamaica Kincaid and Far Tortuga.

There are almost no remaining urban public spaces that aren’t transactional. We know such spaces are good for the well-being of the public, but in a place like New York, where every inch of non-commercial space means hundreds of dollars lost, even “public square”-type spaces require huge corporate investment and are ever encroached upon by people selling iPhone cases and artisan popsicles (I’m looking at you, High Line). Public libraries are some of the last such spaces, but they can’t afford to behave like their commercial peers–they have to balance their anticipation of patrons’ needs and interests with the delivery of community services and the dissemination of information. All on a fraction of the budget of the “privately owned public spaces” scattered throughout New York’s tonier neighborhoods.

All of which is to say: modern public libraries, even as people are still drawn to them, might be under too much pressure to be able to deliver the experience people who privilege pleasure reading crave the most: the accidental encounter with a book, the conversation between the self and the stacks.

That’s where the little library seems to come in, somewhere in the crevice between a librarian’s careful collection and what might otherwise be trash. But the encounters my neighbors and I have when we leave and take those books aren’t pure kismet, either; they’re the product of a neighborhood where someone can afford to spend $26 on a new hardcover and, a few months later, leave it for a stranger. That might not be enough to “foster curbside literacy.” Sometimes, as I learned when I was a bookseller and a teacher, to get someone to read something new you have to actually walk them to the shelf and put the book in their hands.

Photo courtesy of Karen B. Nelson.