“I believe the novella is the perfect form of prose fiction. It is the beautiful daughter of a rambling, bloated ill-shaven giant (but a giant who’s a genius on his best days).”

—Ian McEwan, “Some Notes on the Novella”

1.

I am consistently enamored with the form of fiction called the novella. I think my first book might be one, even though the cover declares it a novel. From where did this anxiety about calling the book a novella come? Perhaps from the rhetoric that surrounds the novella today, a rhetoric that argues, implicitly or explicitly, that the novella is a smaller brand of novel, underdeveloped, minor, feminine. I am here to argue it is not.

2.

Judith Leibowitz in Narrative Purpose in the Novella (1974) offers perhaps the best summary of the affective work the novella performs: “Whereas the short story limits material and the novel expands it, the novella does both in such a way that a special kind of narrative structure results, one which produces a generically distinct effect: the double effect of intensity and expansion.” Tony Whedon echoes Leibowitz’s claims in his “Notes on the Novella”: “Overall, the novella’s general effective is swirly and gunky. Limited in pages, it is implosive, impacted.….”

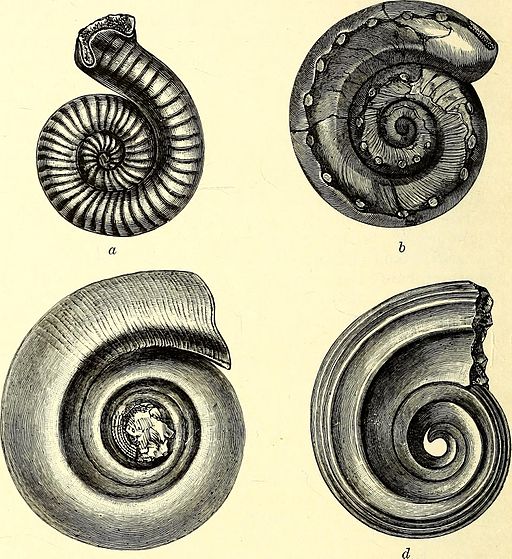

In other words, while other fiction aims outward, the novella curls in, coiling around itself until there’s no distinction between the story’s body and the story’s shell.

In other words, the novella is the fiction of collapse.

3.

In The Art of Fiction, John Gardner says the novella “moves through a series of small epiphanies or secondary climaxes” and “follows a single line of thought.” In fact, the novella might be read in one sitting, and as such, it is susceptible to Poe’s single effect theory. However, unlike the short story, the novella occupies the entirety of the artifact of the book; it is not tucked firmly between other pieces and therefore nested within a larger arc. The novella asks for autonomy while also begging less of your time. This is how the novella is slender but gaping.

4.

According to Kyle Semmel in his essay, “Revaluing the Novella,” these are the characteristics of the form: it must be more controlled, tighter, contain an element of performance, exhibit neat cut-offs, and employ degrees of framing. In essence, the novella is a narrative that privileges succinctness and compression, that in its execution, reveals its architecture, permits us to see its scaffolding.

5.

Furthermore, the novella implicitly argues that there is long-form fiction other than the tome-like bulky blocks of book that outline the concerns of the historical majority. In effect, the novella—in its very existence—is always already political.

6.

The novella is a form that requires brevity and concision—an attention to compression—while simultaneously gesturing toward a larger, expansive idea. In this way, as Leibowitz claims, the novella’s function is similar to that of the fable or parable, which uses a succinct fictional narrative to convey a more capacious tale: “The novella is eminently a narrative of suggestion […] The action in a novella does not give the effect of continuous progression, of a large area being covered as in the novel, but of a limited area being explored intensively.” The novella manipulates scope, offering a refined and dense narrative that feels much larger in scale than it is.

Put another way, the novella declares, “I can say more with less” and then it does.

7.

The novella embraces pause and pattern and gesture. Therefore, as Whedon notes, the uptake of the novella is ever-bound to that of allegory: “The symbols in novellas—religious, Freudian, Jungian, and Marxian—present themselves orchestrally in the form of leitmotifs that dovetail with disparate time sequences to create a strong over-arching moral theme: hence the novella’s connection with allegory.” Because the novella can only craft characters as profiles and because it creates thematic resonance and meaning through suggestion rather than explicit statement, beneath the novella there is always something veiled and covert. This is why the novella lends itself to re-reading—it wants you to return.

8.

The novella has its own taxonomy. In Forms of the Modern Novella (1975), Mary Doyle Springer identities five types of novella based on rhetorical function:

- The serious “plot of character” where action is resolved to serious effect in three variations: a.) simply revealing the character, b.) showing the character learning, and c.) showing the character learning and also profiting from what she learns.

- The degenerative or pathetic tragedy consisting of “relentless, relatively simple and swift degeneration of a central character into unrelieved misery or death.”

- Satire which whether loosely plotted or episodic, chooses the novella because “the object of ridicule is singular rather than a compendium of the follies of mankind.”

- Apologue which looks like a realist or conventional story but unfolds with a clear moral in the same way a fable, allegory, or parable might.

- The Example, a subclass of apologue “often dealing with a single character in incidents which are not plotted to aim at our feelings for the particular character but instead to make use of our feelings for didactic ends, for exposing this character through his actions, as one example of a large human type.”

Later, Gardner categorizes novellas in The Art of Fiction not by genre but by structure. Semmel summarizes Gardner’s three designations as single stream (“a single stream of action focused on one character and moving through a series of increasingly intense climaxes”); non-continuous stream (“shifting from one point of view or focal character to another, and using true episodes, with time breaks between”); and pointillist (“moving at random from one point to another”).

No one notes that the novella is just like the novel but shorter, smaller, less.

No one notes the ways in which the novella is merely a long short story.

9.

And so, though the term “novella” takes the suffix “-ella,” conventionally used to denote the feminine or diminutive form of the root word, the novella is not an immature or effeminate novel. It is not the novel’s “daughter,” as McEwan claims. It is a unique form defined not by its word-length, but by its relative characteristics, its singular structure and unequalled form.

Therefore, I would like to argue this: the novella is not a work of fiction between 15,000 and 40,000 words. Rather, a novella is a book-length work that uses conciseness and unity to create a narrative of suggestion that feels at once compressed and expanded. The novella is slender but gaping. It embraces pause and pattern and gesture. It declares, “I can say more with less” and then it does. It is not an unwieldy short story but cohesive, taut, succinct. It is the novel’s architectural foundation, the stripped and fleshless core that argues the frame of a story might be enough. The novella is a kind of constellation. It is not less than the novel. In that it crafts and calcifies a story world, harnessing concision and brevity to widen the scale and possibilities of our own, the novella might be more.

*

Deepest and most sincere thanks to the members of my Fall 2015 novella course at Denver’s Lighthouse Writers Workshop for working with me through, around, over, and beyond these concerns.

Image: “A guide to the fossil invertebrate animals in the Department of geology and palaeontology in the British museum (Natural history),” 1907. From WikiMedia Commons, public domain.