Iran has produced one of the world’s greatest national cinemas, stretching back to before the Islamic revolution. The films have won numerous international awards, including the Oscar and the Golden Globe, as well as the Cannes Film Festival’s Golden Palm and Jury Prize, the Venice Film Festival’s Golden and Silver Lion, and the Berlinale’s Golden and Silver Bear.

Yet, despite the accolades, Iranian movies are more discussed than seen in the United States. Many have heard of Iran’s internationally renowned directors, like Abbas Kiarostami, who has been making films since the 1970s. In the Guardian’s 2013 listing of “the world’s best directors,” Kiarostami was ranked number six overall and first among non-American directors. But he was refused a visa to enter the U.S. in the year after 9/11, even though he’d been invited to this country by the New York Film Festival and Harvard University. The closest an Iranian film came to enjoying the attention of the American mainstream were Majid Majidi’s Children of Heaven, which was nominated for the Oscar for best foreign film in 1998, and Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation, which won the Oscar in 2012.

Yet, despite the accolades, Iranian movies are more discussed than seen in the United States. Many have heard of Iran’s internationally renowned directors, like Abbas Kiarostami, who has been making films since the 1970s. In the Guardian’s 2013 listing of “the world’s best directors,” Kiarostami was ranked number six overall and first among non-American directors. But he was refused a visa to enter the U.S. in the year after 9/11, even though he’d been invited to this country by the New York Film Festival and Harvard University. The closest an Iranian film came to enjoying the attention of the American mainstream were Majid Majidi’s Children of Heaven, which was nominated for the Oscar for best foreign film in 1998, and Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation, which won the Oscar in 2012.

I teach courses on Iranian film and literature, and this fall I am showing Iranian movies as part of the Nadi Cinema series at the University of Arkansas. People often ask me where they can get movies or find more information. I would like to share some of my resources.

Where to start

If you are considering what to watch, first check out a list like “Essential Iranian Films” created by Kenji for Mubi, or Houshang Golmakani’s “The Iranian Film 50” at Fandor. They both include many classics.

Most of the movies available and studied are art-house films from after the Islamic revolution, but Iran also produces many popular entertainment movies. Unfortunately many of these popular films are not available with English subtitles. Tahmineh Milani’s Ceasefire and Kamal Tabrizi’s The Lizard are two examples of box-office hits that can be seen with subtitles.

There also are directors, such as Ebrahim Hatamikia and Masoud Kimiai, whose works resonate with Iranians but are considered less crafted and are not popular with international festivals. Hatamikia’s major work Glass Agency, and Kimiai’s seminal work Qaisar–both much discussed by Iranian critics–are still not available with subtitles. (You can find other films by Hatamikia and Kimiai with subtitles.)

For reviews about the movies–outside of the usual places like IMDB or Variety–one website I recommend is Film Sufi, where you will find informative reviews of more than 60 Iranian films.

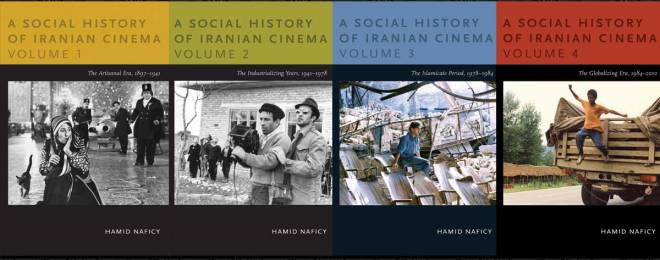

To delve deeper, there are more than twenty English-language books on Iranian cinema. For an overview, seek out such surveys as Hamid Reza Sadr’s Iranian Cinema: A Political History. The most comprehensive resource is the recently published four-volume collection A Social History of Iranian Cinema by Hamid Naficy, who has done invaluable work on Iranian cinema for the past thirty years.

Unlike many national cinemas, you also can find books on special topics in Iranian cinema by film scholars and critics. For example, there are a number of books on important directors Asghar Farhadi, Abbas Kiarostami, and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. In Shi’i Islam in Iranian Cinema: Religion and Spirituality in Film, Nacim Pak-Shiraz traces spiritual and religious ideas in Iranian films. Pedram Khosronejad edited a volume, Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema: Religion, Martyrdom, and National Identity, that discusses Iranian war movies, especially in relation to the Iran-Iraq war and its effect. Farhang Erfani’s Iranian Cinema and Philosophy: Shooting Truth treats a selection of Iranians films using western philosophical theories. Negar Mottahedeh, in Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema, writes on the role of allegory and gender in post-revolution Iranian cinema. And in two books–Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present, and Future and Masters & Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema–leading scholar Hamid Dabashi contributes his personal experience and theoretical perspectives on the relationship and development of Iranian literature and cinema.

Unlike many national cinemas, you also can find books on special topics in Iranian cinema by film scholars and critics. For example, there are a number of books on important directors Asghar Farhadi, Abbas Kiarostami, and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. In Shi’i Islam in Iranian Cinema: Religion and Spirituality in Film, Nacim Pak-Shiraz traces spiritual and religious ideas in Iranian films. Pedram Khosronejad edited a volume, Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema: Religion, Martyrdom, and National Identity, that discusses Iranian war movies, especially in relation to the Iran-Iraq war and its effect. Farhang Erfani’s Iranian Cinema and Philosophy: Shooting Truth treats a selection of Iranians films using western philosophical theories. Negar Mottahedeh, in Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema, writes on the role of allegory and gender in post-revolution Iranian cinema. And in two books–Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present, and Future and Masters & Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema–leading scholar Hamid Dabashi contributes his personal experience and theoretical perspectives on the relationship and development of Iranian literature and cinema.

In addition, there are documentaries on Iranian cinema. Vice TV, for example, made a short piece called Inside Iranian Cinema. Jamsheed Akrami has also done a few documentaries on Iranian cinema, but they are hard to find. A good documentary that you could find–and I recommend–is Iran: A Cinematographic Revolution.

Where to find the films

For the Nadi Cinema series, my goal was to show films from both before and after the Islamic revolution and to include directors that traverse both eras, such as Abbas Kiarostami, Bahman Farmanara, Dariush Mehrjui, Bahram Beyzaie, Parviz Kimiavi, Masoud Kimiai, Amir Naderi, Naser Taghvai, and Ali Hatami. I wanted to look for unique features of the works produced under the Pahlavi dynasty and the Islamic Republic, and consider how specific works reflect traditions and changes in Iranian society. Yet while resources to discuss the films exist, there are few movies from before the revolution that are available with subtitles and in good-quality prints.[1] I hope this situation changes in the future, but for now here are some general resources for Iranian films I recommend.

A great place to start is your school or public library. Even in places like the Fayetteville Public Library in Arkansas, you will find around twenty-five Iranian films, from movies that have played in the art-house circuit, like Mehrjui’s Leila or Kiarostami’s Close Up, to popular comedies like Iraj Tahmasb’s Pastry Girl or Saman Moghadam’s Maxx.

The typical streaming sites like YouTube and Netflix also carry Iranian movies. Amazon, for example, has around thirty Iranian films available for streaming, which includes great works such as Bahman Ghobadi’s Turtles Can Fly, Mehrjui’s The Cow, and Jafar Panahi’s Offside. In addition, the iFilm Network is an international broadcasting channel of IRIB (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting) that on specific times shows different movies dubbed in English. These films are mostly comedies, romances, and family dramas similar to what you may see on the Lifetime TV channel. The iFilm Network is a good place to see what is approved and ordinarily shown on Iranian TV.

Another source is the online distributor IMVBox, which includes harder-to-find Iranian movies for streaming. IMVBox wants to support the Iranian film industry and directors by providing a legal venue for the works–they have told me that they hope to expand their list and continue to add English subtitles to both art-house and popular Iranian films.

Another source is the online distributor IMVBox, which includes harder-to-find Iranian movies for streaming. IMVBox wants to support the Iranian film industry and directors by providing a legal venue for the works–they have told me that they hope to expand their list and continue to add English subtitles to both art-house and popular Iranian films.

If you want to buy the films, you can find some in places like Amazon. Another source is IranianMovies.com, though it is not clear what legal rights they actually have for the distribution. When searching their site, make sure to look for the list of films with subtitles and check for the rating of picture quality.

A number of American distributors, such as the Global Film Initiative and New Yorker Films, have a few Iranian films in their lists. Facets, in particular, has a great selection. You can buy DVDs of films directly from them.

On the other hand, there are Iranian film distributors, such as DreamLab Films and Noori Pictures, that focus on presenting the films in movie theaters and film festivals. At their sites, you can find where their films are being shown and what awards they have won. You can also learn about what films are coming out by checking Iran’s own Fajr International Film Festival. Each year, the festival showcases many new films.

The best place to see the films in theaters is at a film festival. Many festivals throughout the world show Iranian films. In fact, there are even annual Iranian film festivals in different American cities, such as San Francisco, Houston, Chicago, Boston, and Los Angeles. These festivals present rare opportunities to see works that may not be available otherwise. They also provide a venue for Iranian filmmakers living outside of Iran.

A number of important Iranian directors now work outside of Iran. Some, like Kiarostami and Farhadi, make films outside of the country but live in Iran. Others, like Mohsen and Samira Makhmalbaf, Amir Naderi, and Bahman Ghobadi, live in exile. Some of these directors continue to make films in Persian, or films that relate to Iran. A few, such as Shirin Neshat and Marjane Satrapi, have become directors while living outside of Iran, yet they continue to make works that deal with Iran.

There also are directors of Iranian decent. Some, like Ramin Bahrani, make films that are not related to Iran or his Iranian heritage. Others make films about the Iranian diaspora, such as Desiree Akhavan, or make films in Persian that are set in Iran, like Ana Lily Amirpour and Maryam Keshavarz. The works of many of these directors may be seen and discussed at the different festivals.

Please feel free to share your favorite resources in the comments.

————–

1. For those who are interested in Iranian films from before the revolution, you can find the following available with English subtitles, though the quality may vary: The Cow and The Cycle (Dariush Mehrjui); Ragbar and Stranger and the Fog (Bahram Beyzaie); The Report, Homework and Traveller (Abbas Kiarostami); Dash Akol (Masoud Kimiai); Still Life (Sohrab Shahid-Saless); Prince Ehtejab (Bahman Farmanara); The House Is Black (Forugh Farrokhzad); Tangsir (Amir Naderi); and the short documentary films of Kamran Shirdel.