Since my last post, I’ve said goodbye to my twenties. One minute I was a flower opening, the next I’m not allowed to carry a children’s lunch pail or purchase fake Uggs anymore. I’m reluctant to buy into the notion that thirty is the age when you should become the person you’ll be until you die, and the age at which you should stop wearing glitter. But if the rest of the world expects age to herald change, there are a few habits I’d like to tilt toward or away from in the writing department–and not because my youthful metabolism will soon grind to a halt. (Trigger warning: I’m not getting rid of my crop tops.)

Lift heavy weights

If we write poems for long enough, the way we know how to make a poem (knowledge that can easily be mistaken for our “voice”) can stop fitting what we have to say. If no one calls me out, I’m a slave to the iamb and a good chiasmus–I can make both happen in the poetic equivalent of noodling, but that’s like lifting the same weight again and again–you won’t build any new muscle that way. (See: John Williams, recycling of Star Wars themes since 1977.) Artists who reinvent themselves, or at least give their materials and approach a set of useful constraints, get swole.

I think of Marianne Moore’s habit of creating obsessively syllabic English lines (as in “The Steeple-Jack” and “No Swan So Fine”) and Charles Wright’s declaration that he never writes a line with an even number of syllables. There can be something almost translated-sounding about Wright’s lines, and the first time I read “The Steeple-Jack,” the way Moore’s syllabics forced the lines to break was just the element to bring me out of my lazy lyric-reading mode and into her strangely observed world. The lesson: once you’re old, you must find a way to resist the musical crust that can form around poetry whose making is informed by centuries of other poetry in the same language.

Don’ts after thirty: musical crust, Jurassic Park entrance music.

Argue

Poetry has an enormous engine of rhetoric behind it. This is something that poets rarely talk about–either because no one has given us the vocabulary, or because we’re schooled to think poetry and argument are opposites. I’d like to reignite, in my writing, an awareness of Linda Gregerson’s idea of the rhetorical contract in poetry: “poetry, like public speaking,” she writes, “has a suasive agenda: the poem may affect the contours of solitary meditation or unfiltered mimesis, the recklessness of outburst or the abstraction of music, but it always seeks to convince, or coerce, or seduce the reader; it is never disinterested …”

I’m a natural arguer, and I’ve often wondered whether the part of me that writes poems and the part of me that slams down my fist at the dinner table are separate. But in poetry, even so-called pure expression, it seems, has an agenda: listen to me, it says, here’s why you should.

Last week I wrote with some 12-year-old girls. They produced a number of poems in the voices of trees (we were seated in a lush Brooklyn park). The poetic argument has so much more freedom than the one presented to a jury or to one’s dinner companion: I am a tree on a hill, and these are my comrades, went one girl’s poem. Who wouldn’t want to see that proof?

We’re lucky to live at a time when great numbers of poets are re-negotiating the presence of argument in poetry, asking how poetry can not only contribute to conversations around war, rape culture, and racial justice, but also how it can take action. To dismiss these attempts as one-note “political poetry” is to ignore the history of the lyric. “Impediment produced the lyric voice,” writes Gregerson. That is to say, one sings because something is in the way of what one wants, whether that is sex, as in Gregerson’s case studies of Marvell and Herrick, or whether it’s freedom.

Don’ts after thirty: coyness when Andrew Marvell just doesn’t have time for that.

Divert that river

In the annals of writerly maxims, there’s one that drives me extra crazy: “first thought, best thought” or “muse vs. editor” or “banish the critic.” The people who say these things mean well; they recognize that most of us so police our own thoughts that we can’t even bring ourselves to doodle on a blank page. But a side effect of this kind of talk is to make writers feel as though writing must be, in its first stages, some kind of pure self-expressive vomit–that a pause to search for the right word or question one’s motives is like building the Hoover Dam, making the Colorado River run dry and gradually parching Mexico.

During the past two years, I’ve been writing about something I’m quite interested in–the history of computing and the life of Alan Turing–but couldn’t quite put my finger on why I was interested. Did I want the answer to a particular question? Was I simply attracted to the ways mathematicians and engineers had tried to solve early artificial intelligence problems? Was I drawn to the myth of Turing: his genius, his early death? I didn’t want to write a “biography in poems,” because I felt that a lot of biographies-not-in-poems had done the man and his work greater justice. So I kept challenging my attraction to the material. Eventually, the questions about why I was interested gave me a way to put a first-person voice into the work, and brought me around to another way to approach the personal and scientific histories I was reading about. Once the critical voice joined the choir, I found it easier, and more satisfying, to keep making work: I was no longer translating Turing’s life into poems, but using poems as a medium to process my understanding of his work and my own curiosity about it.

Don’ts after thirty: long showers west of the Mississippi. You know better.

Use gizzard stones

When I was younger, I had a certain faith that there was a through line between any ideas that attracted me (e.g. particle physics and the binding of Isaac). This faith made my high school English essays impenetrably dense bricks of metaphor, and probably made me intolerable to hang out with.

Nevertheless, now that I’m thirty I’d like to restore that faith. The stage of a project in which one is slowly building a bridge from one idea to the next is probably the most exciting part, right next to the part where one throws the pages all over the room and cries.

Did you know: dinosaurs and birds who lack grinding teeth use gizzard stones, or gastroliths, that act as coarse teeth to help break down food. What was missing from my youthful connection-fest was a gastrolith. Now that I’m entering my fourth decade, to keep making work that interests me I must sharpen a large one, insert it in my gizzard, and start vigorously consuming everything.

Don’ts after thirty: unassisted digesting.

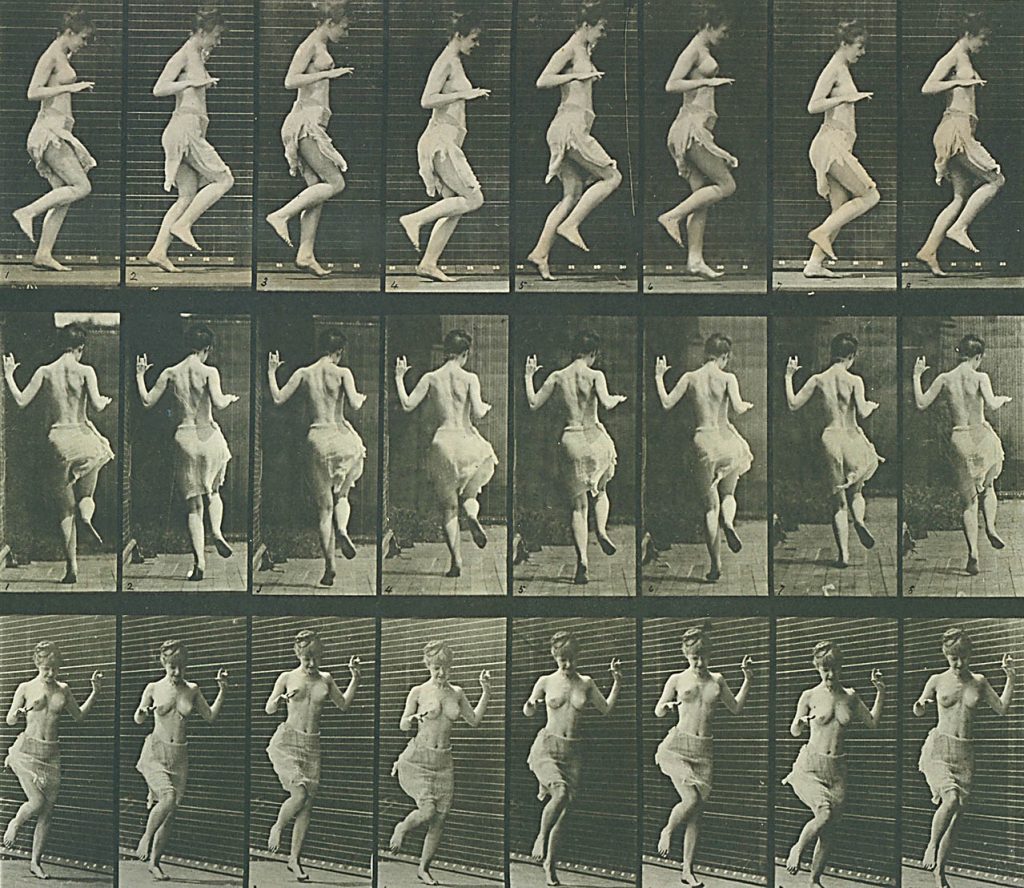

Image: Muybridge, Eadweard. “Woman Ricochetting on One Foot.” 1887. Collotype sheet. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.