Nonfiction by Norma Crawford Tomlinson for MQR Online.

In 1880 my grandfather, George Clinton Hafford, a medical student at the University of Michigan, wrote to his cousin Cora:

Dear Cora,

I sat down to read this evening, but somehow my thoughts kept wandering to you, and I’ve put up my book to talk to you. I feel so queer tonight, as if something was going to happen. It’s been coming on all this afternoon. Now to make it perfect I spose that some calamity should occur. But you know I’m not very superstitious. I’m getting homesick, aren’t you glad? Well, I’m not for I can’t come home for over two weeks yet and only a short time.

Pulled from a packet of letters tied with string, stuffed into an oblong box, this is the only letter I can read. The others are written in a faded short hand. The box is old too. Gold leaves and twisting vines encircle “Gilbert: The Chocolates of Connoisseurs.” Sweet chocolate, whole milk, raisins, fresh fruits, egg whites (the ingredients number nineteen) are printed in small gold letters along the side. Although Grandfather’s letter, written on heavy lined paper, is not fragile, I unfold it carefully.

Pa wrote to me to come home two weeks ago. I’ll tell you why I can’t, but I wish you would not tell anyone. I am a member of the Ann Arbor Dramatic Company, and we are working very hard on a play we have been rehearsing four times a week of vacation in the adjoining towns.

Grandfather? A fledgling thespian? When I close my eyes, I see him, a man in his seventies, wearing a Panama hat, a white starched collar (I have never seen him without a tie), bounding down the back steps of his Queen Anne house painted the color of heavy cream. He pauses, takes the cigar from his mouth, watches me lean back and forth, pumping for all I am worth. When he gestures toward the dusty Ford parked in the drive, I leap out of the swing, falling on one knee.

Grandfather leans across the black satchel wedged between us, slams the car door. We careen down the hill, past Grandmother’s blue spruce, hydrangeas heavy with dew, past my teapot toppled into clipped grass beside tiny cups. Grandfather’s freckled hand guides the steering wheel, the ruby on his little finger shining like a drop of blood. Although he slows at the bottom, the tailpipe scrapes anyway. Grandfather squints under bushy eyebrows, looks both ways, makes a sudden furtive dart leaving Irwin Avenue. After we cross Superior Street, then Saint Clair, and veer right on Harrison, Grandfather guns the motor. We head for open country.

A tanager with scarlet shoulders whirls out of long grass. Grandfather points to a squirrel that flips his silver tail and chases another squirrel up a tree. We pass white farmhouses with columned porches, faded barns, hay stacked into points. After Grandfather brakes for a hairpin turn, we enter a dim forest of ancient conifers, I put my hand on the black satchel, turn to Grandfather:

This is the forest primeval.

The murmuring pines and the hemlocks

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic.

Grandfather takes the cigar out of his mouth, answers:

This is the forest primeval; but where are the harts that beneath it

Leaped like the roe, when he hears in the woodland the voice of the huntsman?

He pats my shoulder. Longfellow is one of his favorite poets. When Grandfather was growing up on the farm in the Miland, he thought he might become an American poet. “The only thing that carried me through long winter months of mindless chores was reciting those splendid poems out loud to myself,” he told me. If his younger sister, Hattie, had not died of scarlet fever during the epidemic of ’78, he might never have studied medicine in Ann Arbor.

Although we seldom talk during our country rides to visit patients, we speak to one another in the language of poetry.

But Grandfather does not talk to Grandmother either. At the breakfast table if she tells him that a purple gentian miraculously appeared overnight in her garden, he will nod his head. If she mentions Tim O’Donnell is riding his bicycle up and down Irwin Avenue after his mother has promised to keep him in bed, he stirs his coffee. If Grandmother reads aloud an editorial from The New York Times by her favorite columnist, he turns his head to listen without comment. Grandmother does not mind his silence. It is his presence she needs to steady her.

During long, lazy afternoons, if my cousins from Glenn Rock or Mount Pleasant are not visiting (sometimes we were fifteen cousins sleeping at the top of a Queen Anne house that smelled of unfinished pine rafters, medical books in cardboard boxes, Grandfather’s castoff Panama hats) I often walked to Grandfather’s office on Superior Street. When I approach the Wyandot Building that Grandfather called Greek Revival, I approach a colonnade of white columns against pale brick under a balcony of iron honeysuckle that hides the long windows. I push open a narrow door, ascend steep steps lighted at the top by frosted glass and “Doctor Hafford’s Office” written in gold letters. President of the Fraternal Order of Eagles and Fellow of the American College of Surgeons, Grandfather is the oldest practicing doctor in Calhoun County.

His patients crowd against the wall of the waiting room. A pretty woman with a blue kerchief tied under her chin and holding a curly headed baby moves over to make room for me on the bench. “Doctor Hafford’s granddaughter” she announces in a loud whisper to the man beside her, swinging his black high-top boot laced to the knee.

I turn the letter over. Grandfather’s handwriting in faded brown ink continues.

I can answer you I have not done it for the pleasure, whatever is in it for that has been slim. But for the hope that it might be the means of making a raise. I know Pa would not like it for he was mad when we played in Milan because it took time from my studies. But my studies have not suffered. This time and if I lose in it I shall lose faith in my financial abilities. Our first date is the 20th of this month, the day that school closes for the spring semester. I don’t know where we will go first. So you see with all that I am—

The grandfather I knew was equipped to deal with crisis. When Jess Cooley’s appendix nearly burst in the office of The Albion Recorder, Grandfather helped carry him across the street to operate on Mrs. Walcott’s dining room table.

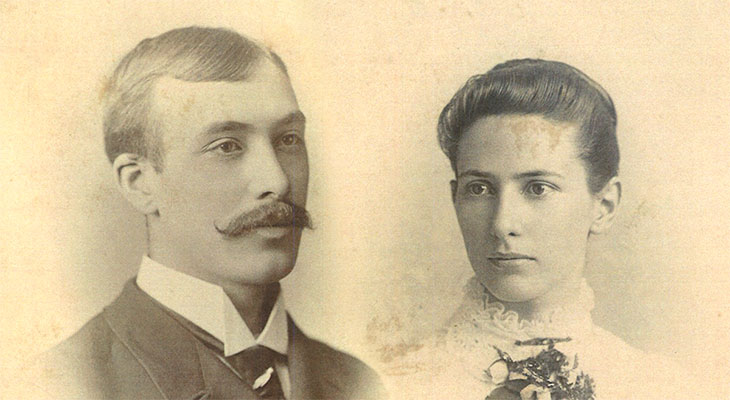

A photograph of my grandparents taken on their fiftieth wedding anniversary, Grandfather leaning on his cane, Grandmother holding his elbow, lies in my bottom drawer. I prefer the two wedding portraits that hang above my desk, taken the day Grandfather graduated from medical school in Ann Arbor. First cousins once removed, they might have been brother and sister, their long oval faces, high cheekbones, the dimple in the middle of the chin. Grandfather’s hair is combed across his forehead (he was bald before he was thirty). A jaunty mustache curled up at the ends sprouts above a full upper lip. His jacket buttons below a paisley cravat tied under a pointed starched collar. Grandmother’s hair, pulled to the top of her head, shows small perfect ears. A sprig of roses pins the ruffled collar together. She is astonishingly beautiful. Her eyes hold mine.

Grandfather’s sentences crowd the margins of the last page of his letter.

I don’t know when the next examination for teachers is to be held, but I will try and find out. I really can’t say whether I will be home next summer or not, It will depend on …

I am behind on bills now and I can’t get them made up somehow. I used three or four months ago more money than I should have for some things which I wanted thinking I could make it up, but somehow it don’t make up, but is bigger than at first. I begin to feel like a bank defaulter. And now I need money for the expense connected with this play. I so hate to ask Pa for it, and I know he hasn’t it too.

Grandmother passed the examination and taught all the grades in a country school near Marshall. I knew that because one sunshiny day, driving out the old Washtenaw Road, Grandmother ordered Grandfather to stop the car, pull off the highway. Grandmother and I approached a frame building with a squat tower, paint peeling from broken windows. The front door, on loosened hinges, was swinging open and shut.

“Every morning when I approached that door my stomach twisted into a knot.” Grandmother took my hand. “It wasn’t until Walker Spears held up his fists, vowed to thrash any boy who wouldn’t let Miss Ulsaver teach the reading lesson that I could maintain order.” Grandmother leaned down to brush the hair out of my eyes. “I was so shy in those days I would cross to the other side of the street in Saline to avoid speaking to a friend.” When she pulled me close and I felt the sharp stays of her corset under the silk dress, I wanted to confess how hard it was for me to stand up on the Grand River street car, pull the cord before all those strangers.

Grandmother believed all fifteen of her grandchildren would grow up to be both beautiful and gifted. And when I visited in Albion, I believed her. That day of sunshine and scudding clouds standing beside a ruined steeple and bronze bell tumbled into long grass, her hand in mine, I was sure some miraculous transformation would occur to turn me into a swan.

I click on the desk lamp, pick up a packet of letters tied with string, turn them over. Letters from Grandfather to Cora written in a code I cannot read, saved in a chocolate box for over a hundred years. One letter, written in English, on lined paper, I hold close to my eyes.

If you come to Saline, I’ll send you a pass. I hope that we will not always be bothered so much as now. I’m in lots of trouble.

I’ve lost my paper correspondence for this week. I guess they will have to do without for now. I wish I could get rid of this strange feeling.

Goodnight,

Clint