Nonfiction by Laura Glen Louis from our Spring 2015 issue.

It’s easy to bypass the cover of Chichester Psalms as it looks like so many of Leonard Bernstein’s vocal scores. The cover is glossy white with his exuberant, trademarked, calligraphic signature a red splash up the left, full vertical, and eating up half the width. I must have looked at this cover a hundred times, dismissing it because it was so present, so declamatory, so red. It wasn’t until I rotated the score that I saw that Bernstein made no lower case e’s, but dragged his fountain pen up to make the capital script E that looks like a reversed 3. His name contains three of them, yet no two are alike—each e is increasingly taller and more emphatic. I am particularly drawn to the last e in Bernstein, that silent e that will not go silently, as in height it nearly attains that of the capital B, and seems poised to splinter off with the last two letters to form a new name, say—Ein(stein). Like his signature, Chichester Psalms is a work that you have to look at obliquely, before the embedded motif reveals its most beseeching meaning, before you can hear how this theme will not go silently, but splinters off to an ultimate, urgent idea, even as it is whispered.

Just forty-eight pages (forty-one proper with many pages of rich front matter), my choral score of Chichester Psalms has held my attention as keenly as a fine, dense novella. Man is roused; he’s invited to the House of the Lord. (Note the passive construction: he has to be awakened, has to be called.) He walks alone, but ever with God; he wars. He asks for contrition; prays for unity. Amen. As the number of plots is finite, art depends on the telling. Laid out in three movements of paired psalms and integrated by a recurring theme—the five-note Urah, hanevel (Awake, psaltery) motif of the first movement—Chichester Psalms is, in turn, a rousing, joyful, lyrical, strident, contentious, violent, holy, humble, and ever urgent invocation for peace.

———

1. Invocation and invitation

Psalm 108, vs. 2: Urah, hanevel v’chinor! (Awake, psaltery and harp)

Psalm 100: Hariu l’Adonai kol haarets (Make a joyful noise unto the Lord)

I had sung Chichester Psalms before, which is not the same thing as saying I know this piece. It was fifteen years ago, I was still new to singing, and Bernstein was a pole vault over Bach and Mozart. I’m a decent sight singer (but not for Schoenberg); I’m a quick study; I love a challenge; but here, and in spite of past experience, in spite of remembering the work with great fondness, it was hard to find footing. Indeed, at the first rehearsal with Berkeley’s Chora Nova, I wondered whether I had only imagined that I had sung this before, as nothing looked familiar.

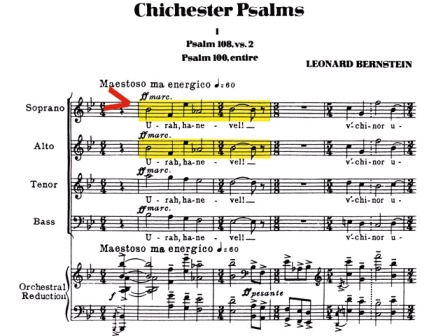

Open the score of Chichester Psalms and a lion leaps out, Rrraaah!! An accented cymbal-tympani-glock-chime-brass-contrabass pick-up slams into the first full bar of 6/4—a percussive, instrumental Hark!—and the singers jump in Maestoso ma energico, percussive and full of majesty, in one of the most demanding openings ever asked of a chorus. Urah, hanevel! (Awake, psaltery!) Every clue you need to understand this piece is in this unifying five-note Urah, hanevel motif (introduced by upper voices, in unison): the urgency of the wake-up call and the dissonance that speaks to man’s struggle between his more noble and savage selves.

This setting of Psalm 108, vs. 2 is only ten bars long, yet in every bar save the last, the meter changes. The meter not only changes but upshifts, from 6/4 to 3/4, to 3/8, and we scramble to stay in the groove. The rest of the line v’chinor urah! is set to a 5/4, 2/4, then a 5/8 bar. More quickening. What’s so hard? Imagine you are running hurdles and the heights of the hurdles are not standard, the distance between them inconsistent. A-irah shahar! (I will rouse the dawn!) staggers across a 6/4 bar into a 2/4 that ends with rolling tympani as the entire chorus leaps to high F, Ah! Throw open your door and come on down.

Don’t be daunted by all those time signatures (even though we were). To put this into some context, Paul Desmond’s “Take Five” (set in 5/4) had hit the charts a few years prior to the 1965 premiere of Chichester Psalms, and back at the turn of the (previous) century, Stravinsky set entire subsections of Firebird in 7/4, and his Rite of Spring is all over the time signature map. If you need a germ for Chichester’s roller coaster opening, look no further. Just note here that with each successive bar, time is halved, and the pulse quickens. Which brings up the question—how would you conduct that? Early on, our guest conductor, Bruce Koliha, confessed to wondering the same thing. With that, we knew we’d have to memorize this and never take our eyes off him.

Ah. Knowing our notes and singing in tune: the one does not imply the other. Easy to look at a note and say, That’s A. But do you hear it as 440 Hz or are you just cruising the ’hood, say with any of the microtones between A and A♭, which is 415 Hz? For singers, there isn’t a key on your clavicle that you can press like on a piano that the highly paid piano tuner has already been through to make sure everything is sympathetic. You have to produce that sound marshaling all your resources: ear, mouth, vibrating vocal chords, posture, diaphragm, abs, glutes, your very height and the wings spreading off your back. When you sing in community, and every singer is dead in the center of the pitch, a hole opens up that everyone can pass through. On the other side is no magical land, no lush gardens, no brilliant light, but there is a palpable sense of other space that is resonance. Physics explicates with mathematically repeating sound waves and oscillations. Then, too, when we sing in the heart of the pitch, it feels—effortless. The pure tone you make pulls you in and you feel you could sing forever, you want to sing forever, you want to stay in that reverberant, expansive place. If you haven’t ever made resonance, you haven’t lived.

So much for intonation. You also have to know the interval, the gap between two notes. It can be sweet, and as carefree as stepping off a curb that is the major third, or the perfect fifth. Or it can be the minor seventh, which requires all the intention of a standing broad jump. It is the minor seventh that is embedded in the opening five-note, Urah, hanavel motif that runs throughout Chichester Psalms, (the F/E♭interval in the phrase B♭/F/E♭/A♭/B♭). You know this interval as the first two notes of “Somewhere” from West Side Story (There’s a place for us). Not only does Bernstein set the first motif with a minor seventh interval, but he wedges the tenors between parallel major and minor sevenths of the basses, and minor sevenths and ninths from the altos and sopranos (A-irah shahar), with major/minor second crunches thrown in, to keep it lively. (The major second is “Chopsticks.” The minor second is a toothache.) I didn’t dare look at my tenor friend, Marty, whom I talked into singing this. (“Come, it’s gorgeous. You’ll love it.”) The poor tenors might have well been asked to sing in a different key. They are on a tightrope of intonation, no net in sight, with the rest of us doing our best to knock them off. From the get-go, Bernstein lays down an internal struggle. Remember this five-note Urah, hanevel motif (Awake, psaltery), because Bernstein brings it back and again, to profound effect.

Why such an aurally demanding opening? Man is somnambulistic. He has to be roused from some mindless sleep. The reward? A grand party, delivered in a comfortable 7/4 meter (4 + 3) for Psalm 100, Hariu l’Adonai kol haarets (Make a joyful noise unto the Lord). Amusing to think of 7/4 as an easy meter, but its constancy is a relief and a mooring after those harrowing opening bars. Once you get the missing quarter note in your body, it’s rockin’. That missing eighth beat is what’s exciting. Its absence propels the music, spills it into the next bar, one cascading into the next, energizing the call. And the call? Come to the House of the Lord.

If that ten-bar intro is a wake-up call, the rest of the movement, the 7/4 Hariu l’Adonai kol haarets (Make a joyful noise), is an infectious, barefoot, sylvan dance, a musical relay. Basses and tenors pass the lines back and forth, and we women cannot wait to jump into the mix, grabbing their landing notes and dancing them forward, all the way until the invitational Bo-u sh’arav b’todah (Enter, Enter, Enter into His gates with thanksgiving), which Bernstein treats with staggered and imitative entries, as once is not enough. Then the whole joyful noise repeats, all stops out, drums, bells, whistles, glocks, every toy in the music box. We whip ourselves into a frenzy, fortississimo and giocoso with Bernstein’s direction “boisterously,” and our conductor’s directive, “savagely”: Bo-u sh’arav b’todah … Hodu lo, Hodu lo, bar’chu sh’mo (Enter into His gates with thanksgiving … Be thankful unto Him, and bless His name). In case we’re too timid to give it all we got, each bar gets a sffz kicker from the bass drum and tympani on that 7th beat—jazzy, propulsive, and sexy as all get out. Our lungs are enlarged, we are enlarged. We’re pumped with endorphins, coasting on ecstasy.

The orchestra slides in to restate the opening theme. The music must die down in order to rebuild, and rebuild it does, as four soloists deliver the last two lines of Psalm 100, and the reduction in texture has the effect of elders stepping forward to declaim with cogent wisdom. Ki tov Adonai, l’olam has’do (For the Lord is good, His Mercy is everlasting), V’ad dor vador emunato (And His truth endureth to all generations). The chorus joins in to finish with sustained, seven-beat chords, one per syllable, one per bar, each note accented and amplified by cumulative crescendos, every syllable an unwavering affirmation: Ki tov Adonai!, with the last syllable held out for nearly three full bars (that’s twenty-one beats), crowned by that cherry: a fermata.

Nowhere in this entire 7/4 section of Psalm 100, not even with the sffz kickers of the previous section, is that missing quarter note more thrilling than in this last choral phrase, one that builds from piano with successive attacks to retake the beginning of each bar and crescendos with rolling timpani to fortississimo, chased by an orchestral repeat of the five-note Urah, havenel motif, but with the first note transposed up an octave, refreshing the phrase. Awake, harp! The effect is not just that of a great party, but the best of all possible parties. Celebratory, invitational, nearly erotic, this is a portrayal of the God not of wrath, but of unbridled joy, exuberant, circular, without end and larger than life. Like Matisse’s La Danse—as if choreographed by Nijinsky.

I believe in science. I believe in the big bang, the ever-expanding universe, empirical evidence, our relative insignificance, the resilience of bacteria. But, when I’m singing Bernstein’s setting of Psalm 100—music this exuberant, this compelling and affirmative, this inclusive—I want to shout, I believe!, thereby confirming the Hasidic belief that singing, ecstatic singing (dancing, contemplative meditation) brings you closer to God.

———

2. (The) David and Goliath (in us)

Psalm 23: Adonai ro-i (The Lord is my shepherd)

Psalm 2, vs. 1-4: Lamah rag’shu goyim (Why do the nations rage)

A friend once said of a poem she had pinned to the fridge, “Every time I pass by, I stop to read it; and every time I read it, I see something new.” Lydia Davis said, in her introduction to her translation of Proust’s Swann’s Way, “One will find, too, that the better acquainted one becomes with this book, the more it yields.” This also can be said of Chichester Psalms. To read this work deeply, including the protean pages of front matter; to absorb the translations; to marry meaning to music; to understand the dynamic markings beyond the mere performing of them; to take in Bernstein’s many considered directives—is to know it as poetry. The essential and nothing but.

Reading deeply is what’s needed to practice well, to break down the music, to find where my part is in unison with other parts (and why); and where the composer uses counterpoint; where entrances repeat across different voices, staggered or modulated, to compound the drama, or to restate the text; but also to create a blurry echo just a bar apart that makes for a dreamlike, musical shimmer. This happens in the middle of the second movement of Chichester Psalms.

Blissfully unaware of threat. This is Bernstein’s directive to the sopranos and altos at that very point of Chichester Psalms, during that lulling, gorgeous, dreamy shimmer. That “blissfully” gnawed away at me, and I had to suppress a knee-jerk feminist reaction. First let’s look at the structure of this movement that makes subtle use of echo.

A single arpeggio from the harp (semplice, senza sentimentalita) launches Psalm 23’s Adonai ro-i (The Lord is my shepherd), in a solo specified by Bernstein to be sung only by a boy soprano. Hang on to that thought.

Sopranos and altos take over, one bar apart (the musical shimmer) with Gam ki eilech / B’gei tsalmavet (Yea, though I walk / Through the valley of the shadow of death); the soloist returns to reiterate Adonai ro-i, lo ehsar, echoed by the upper voices, whose lo ehsar (I shall not want) Bernstein interrupts with—

Psalm 2, Lamah!! (Why? Why?) Tenors and basses cut in allegro feroce (exactly what it sounds like) with Lamah rag’shu goyim (Why do the nations rage), more word painting: you can hear pounding boots, clangs, clashes, sparring. Our conductor said, “Think of gunshots.” In a work that uses no 4/4 or common time, the closest is this section of Lamah rag’shu, which, in cut time, rips right along. Our conductor said, “Spit out the words.”

As the basses sing Yit ’yats’vu malchei erets / V’roznim nos’du yahad / Al Adonai (The kings of the earth set themselves, / And the rulers take counsel together / Against the Lord), the tenors cry Yahad! Yahad! (Together!) no fewer than fourteen times, goaded by the grating rasp. At the end of the verse, the men, spent, are in turn supplanted by—

the sopranos and altos, in the meat of the movement, continuing Psalm 23 where they had left off, again staggered by a bar (more shimmer), Ta ‘aroch l’fanai shulchan / Neged tsor’rai (Thou preparest a table before me/ In the presence of mine enemies), with this directive from Bernstein: Blissfully unaware of threat. While underneath them—

the men repeat, full of fury, the last and the first lines of Psalm 2, ending with Yis’hak, Yis’hak ([the Lord] shall laugh [… in derision]) morendo, whispered, nearly hissed, like bullies banished from the party.

The boy solo returns for the last stanza of the psalm: Ach tov vahesed (Surely goodness and mercy / Shall follow me all the days of my life)

I returned over and again to that “Blissfully unaware of threat,” until a few weeks later, my eyes fell on the Composer’s Note in the front matter: “The soprano and alto parts are written with boys’ voices in mind.” Oh. “Blissfully unaware of threat” for adults is a very different affect than “Blissfully unaware of threat” for children, and therein lies the power. Suddenly there’s innocence, and one that is all the more horrific for the terror bearing down on them, since the men have just sung Lamah rag’shu goyim (Why do the nations rage).

Fast forward to summer: already committed to singing one program (challenging, twenty-first century music), the smart thing to do was to decline a second. I agreed to do both. (Greedy little songbird. Ella Fitzgerald: “The only thing better than singing is more singing.”) The inspired second program? A concert of different settings of—yes: Psalm 23. Synchronicity will not be denied.

I found myself being carried away by ten interpretations of The Lord is My Shepherd, from Gregorian chant to Bach, Rutter, Schubert, Stanford, and McFerrin, sung in Latin, German, French, and English. A quick search uncovered another twenty settings. Guess how many there are? Go on, guess. A—hundred? Hard to say, really. As we were working, someone in that summer pick-up chorus wrote another setting. The inside buzz is that several hundred would not be unreasonable. A thousand. More. Yet, I know of no other setting that is intercut with another psalm, let alone one as strident as Psalm 2. Bernstein, by his operatic juxtaposition, underscores the poignancy and fragility of Psalm 23 and heightens the potential downfall implicit in Psalm 2. This movement speaks to the duality of our nature and underscores the challenge of the meek to hold the line. A sum even greater than the already profound parts.

Psalm 2 was what the Very Rev. Walter Hussey, Dean of Chichester Cathedral, had suggested to Bernstein when he commissioned work for the cathedral’s 1965 music festival. Bernstein obliged, but he didn’t give the psalm its own stand-alone movement, as Handel did in Messiah. He put our darker, warring selves squarely within us. He compressed Psalm 2 into a furious minute and embedded it in the heart of the heart of the work, Psalm 23, from which it bursts forth in all its fury. Art imitating life.

There is in every piece I sing a moment that I look forward to, one above all other beauty, where everything about the piece seems to coalesce, or where the altos are given some gem of a line to sing, altos, who jokingly say “we get the leftover notes,” those notes needed to give harmony its color or fire, but might not make linear sense (“Oh, isn’t that modern?”). Sometimes the gem is just one note, but one which happens to be my money note, that note people will pay money to hear a singer deliver. Usually my money note falls on some crux in the piece. I sing toward that note, I look forward to it, as I look forward to seeing someone I love. I arrive, all is good. Every difficulty in life falls away. I’ve been given a chance to offer up the best of what I have to give.

In Chichester, that sweet place for me lasts an entire phrase and is in the middle of this second movement, when the top two voices come in after the boy soloist, singing the same theme: Gam ki eilech / B’gei tsalmavet, (Yea, though I walk / Through the valley of the shadow of death), Lo ira ra, / Ki Atah imadi (I will fear no evil, / For Thou art with me). The lines are marked Soprano divisi, but because our conductor wanted a blend of soprano and alto voices on each line, he counted off ones and twos to alternate the parts. To my good fortune, I ended up as a one. The ones lead the phrase and set the tone, the twos provide the echo, the shimmer. “Bluesy,” he said. Singing it, I felt as if floating in purity and transcendence, protected in adversity. Alone, yet not alone.

How did Bernstein do this, how did he make me feel the very text he was setting? Maybe it’s the suspension of notes, the harp underlay. Maybe it was because I got to sing the line that leads, and had a phalanx of other women singing one bar later, as if walking behind, echoing, ushering. Echo was used at the beginning of this movement, in the opening boy solo, during which the harp follows one beat behind the voice, with the third beat silent, so that the repeated voice/harp/stillness makes the solo even more stark than if it were truly a capella. Walking is one step at a time and tentative. Alone, yet not alone. Ki Atah imadi (For thou art with me.)

This protean second movement ends with the return of the boy soloist to finish Psalm 23, Ach tov vahesed / Yird’funi kol y’mei hayai, (Surely goodness and mercy / Shall follow me all the days of my life), followed by the upper voices recalling the opening Adonai-ro-i, lo ehsar (The Lord is my shepherd / I shall not want), whose last syllable, the last of this movement, is held out for a staggering eleven bars. I don’t usually have trouble holding pitch but I struggled with that long held A, already demanding for staying in the core of the pitch, and for so long; for creating the spin to keep the note fresh and alive; but also, the A we hold is against an orchestral “rage” played in a different key, C minor, with nearly every chord impacted with clashing major and minor seconds, and tritone crunches. (What’s a tritone? It’s the augmented fourth, an interval so disquieting it is known as Diabolus in Musica, the Devil in Music. You know this interval as the first two notes of Bernstein’s “Maria,” the use of which subtly portends a doomed relationship, even as Tony is transported by new love.) What Bernstein asked of the sopranos and altos—this much unflinching steadfastness against a feral, insistent, dissonant, subliminal male “rage.” And he asked this of children. Though the men have stopped singing, the orchestra underneath rumbles ppp the Lamah rag’shu “rage” motif: while the rage of nations subsides, it is resident, undercurrent, ever ready to burst forth; but faith—quiet, steadfast, unassuming, and, because it was to be sung by boys, innocent—will prevail. It’s a fragile state of balance.

The directive from our conductor on that long, held note: “Sing as if it could go on forever.” It must.

———

3. Contrition and unity

Psalm 131: Adonai, Adonai, / Lo gavah libi, (Lord, Lord, / My heart is not haughty)

Psalm 133, vs. 1: Hineh mah tov, / Umah naim, / Shevet ahim / Gam yahad

(Behold how good, / And how pleasant it is, / For brethren to dwell / Together in Unity)

Unfortunately, the second movement doesn’t end quite like that. When we finally stop and take a breath, the bass drum sneaks up behind boom-boom-BOOM to have the last word, a musical nyah-nyah, with this directive from Bernstein, attaca: cut to the third movement without pause. And what a strident opening. The violins that had been lending distant unison support on that sustained eleven-bar choral A are now joined by all the strings in a cri de cœur I had to turn down every time I listened to it.

The opening phrase recasts the Urah, hanevel (Awake, psaltery) “call to the party” opener of the first movement, but now faster (seventy-two beats per minute versus the sixty I think of as the heart at rest), and replete with anguish and horror, as the strings dig in their bows and drag them all the way to the wood with something nearing violence. In an opening that lasts only nineteen bars, the transformed Ural, hanevel theme is played no fewer than five times (Awake, psaltery, Awake, Awake, Awake, Awake!), with the third iteration’s fortississimo nearly sheering off the top of my brain. Each time I heard it, I could only see, in some synesthetic blast, Picasso’s Guernica.

In between, the music tries mightily to assuage, with calming, ascending, whole-tone scales, alternating with a musical rocking, like taming some wild thing, over and again, until the fifth and final iteration of the transformed Urah, hanevel motif. The strings melt into a series of rising figures starting from D, climbing up an octave to F#, where they hover—before resolving in the key of G. Phew. This phrase is marked senza agitazione (senza, without), a directive subtly different from tranquillo, as it implies the active setting aside of conflict.

All you need to take away from this dense and wrenching nineteen-bar orchestral opener is a sense of struggle: a stridency and great agitation at odds with a pleading calm, and it is calm that prevails. This struggle is further amplified by the shifts in meter before finally settling into the 10/4 that Bernstein sets for Psalm 131 and Psalm 133 vs. 1, a meter he specifies to be conducted “in the shape of a divided 4 beat, adding an extra inner beat on 2 and 4…,” emphases all his. When I try to “air conduct” as written, I see that to lengthen beats 2 and 4, the gesture must be drawn out, my arm must open and open. The text he’s illustrating? Nothing short of contrition.

Adonai, Adonai, (Lord, Lord), Lo gavah libi, (My heart is not haughty) the men begin, semplice, calm, humble, as if on bended knee, accompanied by solo harp (recalling the solo harp used with the boy solo, Adonai ro-i, from the second movement, as if to reclaim some of that innocence and belief), before the upper voices take over with Im lo shiviti / V’domam’ti (Surely I have calmed / And quieted myself). The men rejoin half a bar later, through Kagamul alai naf’shi (My soul is even as a weaned child) until the lyrical phrase comes to unison on the last syllable. The orchestra takes over to repeat the music with an achingly expressive solo from the cello, the instrument most often likened to the human voice.

Chorus returns for the next four lines with great warmth on the text-neutral vowel, “Ah,” which clears the ear for the last two lines of Psalm 131: Yahel Yis’rael el Adonai (Let Israel hope in the Lord), poco a poco rallentando, pp to ppp, slower and slower, quieter and quieter, Me’atah v’ad olam (From henceforth and forever). A solo quartet enters to repeat these last two lines, with Bernstein’s directive to the orchestra colla voce: follow the voice.

After all the push and pull, after the tug of war between rage and faith, between rage and reason, between rage and contrition—after all this, we finally arrive at Psalm 133, vs.1, the last psalm of Chichester Psalms, where we’ve been headed since the downbeat of the piece entire. Hineh mah tov, / Umah naim, / Shevet ahim / Gam yahad. (Behold how good, / And how pleasant it is, / For brethren to dwell / Together in unity.) The yahad (together) that was repeated thirteen times in the second movement as the kings united against God, now reclaims the meaning of unity, not against, but for God, as unity of all peoples is an embrace of a universal higher being, and an embrace of our more noble selves. To make sure we don’t miss the point, Bernstein whispers. He sets these four lines as an a cappella hymn, ppp to pppp, Lento possibile. There is no orchestral support. We are utterly exposed. And in delicacy is humility. Each of the four lines lasts nine slow beats to the bar, with the last line lengthening to a 12/2 meter as Gam yahad is repeated (Together in unity, together in unity.) This then is the final set of psalms: Contrition and Unity.

There are some Amens that run for pages and pages, alone or in counterpoint to other underlay, and each is a vocal marathon. Pity the singer who loses her place. In Rossini’s Petit Messe Solennel, the Amen parallels the Cum Sancto Spiritu for nearly thirty pages. Five-part Amens threaten to overrun the “Gloria Patri” of Handel’s Dixit Dominus. Bruckner’s Mass in E Min has an Amen fugue that is one of the most tonally difficult ever, as the key changes in nearly every other bar. Dvorak’s Stabat Mater ends with Amens scored for eight-part double chorus with a couple of paradisis thrown in, about whose four-minute length at least one audience member said, and breathlessly, “I didn’t want the Amens to stop.” These affirmations are complex, thickly textured, fugal, rousing, exuberant, declamatory, and brimming with drama and passion. The Amen of Chichester Psalms is not one of them.

Chichester’s affirmation is but a single utterance, spread over the last two bars, and lasting twenty-four considered beats, voices and strings in unison on G and with only the second violins adding, on the last syllable, the barest hint of the third on B-natural. This Amen is still, spare, open. Naked. Under this hushed Amen, Bernstein brings back the Urah, hanevel motif in its final iteration, played by harp and trumpets (like taps at dusk), three unhurried beats per note, with the last note held for twelve long beats.

By repeating the opening five-note motif under different texts, Bernstein tied these texts together, as the Urah, havenvel! (Awake, psaltery!) that began as a call to joyful noise, morphs into the anguished struggle between faith and war, and melts by the end of the piece into something akin to tolling bells under a twenty-four-beat Amen. Pianissimo. Very quiet. Dolce. Sweet. Lunga poss[ibile]. As long as possible. And finally, Tutti unis. Of all these directives—very quiet, sweet, longer even than written, as the last note is crowned with a fermata—of all these precise effects Bernstein specified for his last word, the most crucial is Tutti unis. All voices in unison.

———

4. Blissfully unaware / The whole bow

Maestoso ma energico. Con gioia. Pesante. Tutta forza. Agitato molto. Dolce, tranquillo. These are some of the many directives from Bernstein for Chichester Psalms, given in imagistic, mouthfeel Italian. Occasionally, a composer will use French or German, but the standard is the language of Italy, birthplace of many musical forms in the Renaissance. These directives number in the hundreds, yet these hundreds failed to yield the single affect he wanted in the second movement, bar 103, when sopranos and altos sing Ta’aroch l’fanai shulchan / Neged tsor’rai (Thou preparest a table before me / In the presence of mine enemies). Here, Bernstein felt compelled to use English: Blissfully unaware of threat. But, how often would such a phrase occur in music to warrant a permanent address in the musical lexicon? Otello? But was Desdemona unaware of her fate? And, blissfully? No. Blissfully unaware is a singular one-two punch, one that launched my quest to understand this piece.

Blissfully unaware can also describe the lack of full intersection with the text that choral singers sometimes have. Translations are generally given at the front of the score, if at all, rather than being slotted right underneath the lyrics. How then to know what we are singing? Write it in by hand. Given the demands of learning notes, the pronunciation of a language we don’t speak (here, Hebrew), learning some very challenging “asymmetrical” rhythms—few take the time to write in their scores a line-by-line translation between the composer’s directives, the dynamic cues, and colorful notes from the conductor: “Taller vowels.” “Liquid l’s.” “Darker, fuller.” (Does this begin to sound like sex? But, do we want anything less than the sublime, anything short of being deeply moved, of being genuinely connected?)

Confessions from fellow choristers: “The Psalms are some of my favorite poetry and I have been trying to understand the role of the music in this piece.” And “… how mindless I am sometimes as I go through the motions while singing.” Then there was the soprano who was dancing whenever the men “raged” in the Lamah rag’shu goyim section, her seduction by percussive rhythms proving music’s other, darker power: to marry sensuality to violence.

I, too, am guilty of occasionally not knowing what I’m singing about, as the score tells me how to sing it. I know when to swell, when to hush, when and what to feel even if I don’t know word for word why. The composer relays all this in the line, the dynamics, the intervals, the harmonies/dissonances, the tension in silence (the anticipation, and of what?), just as the composer communicates these same to instrumentalists. But, singers have text, we have language, we have meaning. We are telling a story. Don’t speak Hebrew? No problem. We learn phonetically. False? Disingenuous? Did Meryl Streep speak Polish? Yet, she slipped into the skin of Sophie. We believed her. We are not Meryl Streep, but to sing well we have to begin to understand the lyric as well as this actress understood Sophie Zawistowski.

Could I imagine singing this in anything but the (transliterated) Hebrew in which the Chichester Psalms are set? No. Much has been written about the aborted musical, The Skin of Our Teeth, which Bernstein cannibalized for spare parts to make this phoenix (including the lyrical boy solo, Adonai ro-i), tossing into the mix a discarded opening from West Side Story (Lamah rag’shu goyim / Why do the nations rage). Artists, inventors, scientists chasing one idea stumble on another. Penicillin. Prussian blue. Chocolate melting in a shirt pocket (microwave). The elixir of life (gunpowder— unbelievable irony.). Perhaps this happened for Bernstein. Perhaps The Skin of Our Teeth was not the end game, and the themes he imagined had not yet found their lyric, their language, their raison d’etre. Chichester Psalms may have been exactly where Bernstein was headed all along. The Thorton Wilder inspired him to set down what he was hearing, and nudged by a prompt from the Dean of Chichester, Bernstein wrought musical alchemy. Sing Chichester Psalms in English? To translate the Hebrew of the Psalms into English would alter the curves, stresses, and dynamic of every phrase. Indeed, at the success of the initial performances, Bernstein was asked, entertained the idea of, and briefly worked on, an English language version of Chichester Psalms, only to abandon what would amount to making a zebra out of an Arabian.

In Leonard Bernstein in Salzau, the documentary of the youth orchestra rehearsal at the Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, one student said: “He’s not just a time beater, he’s making music.” Making music is high art. Bernstein demanded the most of every musician, to give every note its due, to understand the arc of a phrase, to feel the primal urge, the connection to the earth, to stretch a glissando and hit every tone all the way down. “I want to feel sick,” he said, pointing with drama to his gut. Many times he said to the strings without missing a beat: “The whole bow. Ugh, ugh, ugh. (Use) the whole bow.”

If blissfully unaware of threat is his way of cocooning the innocence of youth, for whatever brief time it can prevail, then the whole bow is his insistence that we make the best of what we are given. That we understand what it is we are expressing, that we give our all, not so much that we be perfect, but that we dig deeply to drag up what even we don’t know we’re capable of, in music, in life, and especially in our response to the world. To do less is not only a waste, but an affront. The whole bow is what we see in the beginning of that third movement as Bernstein conducts the premiere of Chichester Psalms, down bows attacked with a visual and aural violence. We hear it, we see it, and we are more alive for the gift of it. The whole bow is the entirety of this piece, three movements and nineteen minutes of musical persuasion that urges with invitation, horror, internal struggle, and supplication: Unity.

The psalms were written a few hundred years after David went up against Goliath. In 1963, two years before Bernstein composed this piece, Buddhist monk Thich Quan Duc set himself afire in religious protest. Later that year, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was murdered. Kennedy, assassinated. America was sucked into Vietnam, and with two World Wars, the Holocaust, the Armenian massacre, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Nanking behind him, these Psalms were the lyrics Bernstein chose to respond to his time. Urah, hanevel, v’chinor! (Awake, psaltery and harp). Bo-u sh’arav b’todah (Enter into His gates with thanksgiving). Adonai ro-i, lo ehsar (The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want). Lamah rag’shu goyim (Why do the nations rage). Adonai, Adonai / Lo gavah libi, (Lord, Lord / My heart is not haughty). Hineh mah tov, / Umah naim, / Shevet ahim / Gam yahad (Behold how good, / And how pleasant it is, / For brethren to dwell / Together in unity).

Does music have the power to stop wars? Wladyslaw Szpilman, starving in the Warsaw Ghetto, parlayed Chopin not only for his supper, but for his life, having been found, fed, and hidden by a Nazi officer whose morality and humanity were still intact. Vedran Smailović played his cello in the semiruins of the National Library during the siege of Sarajevo, a piece known as Albinoni’s Adagio in G minor (fragments posthumously made flesh and whole by his biographer, Remo Giazotto), and which, because I first heard it in the film Gallipoli, is indelibly married in my mind to the waste, the godless irony, and the maddening futility of war. Messiaen wrote The Quartet for the End of Time in POW camp Stalag VIII-A, on paper given by a sympathetic guard, a monumental work limited to, and inspired by, the few musician-prisoners at hand (clarinetist Henri Akoka, violinist Jean le Boulaire, cellist Étienne Pasquier, and Messiaen himself on piano), a piece performed on marginal instruments, in an unheated hall, snow in the stalag (life imitating art), for prisoners and captors alike, a sad, beautiful, seemingly bleak, yet affirming work, the center of which is “Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus,” louange (praise) of Jesus as the Word, a work that is nothing if not the whole bow. Hear this and weep. But—hear this and also feel alive. Many evenings I have left home after yet another difficulty only to arrive at rehearsal so depleted in more ways than I thought could be possible, that I just sat in the car while night descended. I’ve long adopted the mantra, “No bombs are dropping in Berkeley, all is good.” I could also say, “Alone, yet not alone.” After a few minutes, I would make myself go in, and every time, after singing for only a few minutes I would be rescued by music’s potion, such is the transformative power of singing, of music, of making music. But—can music stop wars? What happens when the singing stops? Are we ever only a few resolved chords from hitting the panic button?

In program notes for the Charlottesville Symphony performance, Michael Slon wrote of Bernstein having reset the music from The Skin of Our Teeth. Of the Urah, havenel theme, he wrote that originally “the motive that opens Chichester Psalms (and runs throughout) appeared with the words ‘Save the human race.’” After three millennia we are still warring, with passion and—even more disturbing—with chilling dispassion. Music’s gift to soothe? We can only ask so much of it.

Photo credit: Chichester Psalms by Leonard Bernstein. Copyright 1965 by Amberson Holdings LLC. Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company LLC, publisher. Boosey & Hawkes, agent for rental. International copyright secured.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This excerpt is featured content from the

Spring 2015 issue

For ordering information or to find out more about the contents of this issue, click here.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .