Slightly mineral, the fresh morning air arrives cool from a slight breeze off the Shilshole Bay. After moving around and traveling so much recently, I feel I need to sit still for a while. I take a thermos of strong coffee to the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks, locally known as the “Ballard Locks,” where I plan to think and look at the water. They’re curious, the Ballard Locks. Here, Seattle’s main freshwater lakes, Lake Washington and Lake Union, mix and mingle with the salty inland sea of Puget Sound. The Ballard Locks connect the bodies. They are intricately engineered to move hulking commercial ships, tugs, and barges—as well as smaller pleasure crafts and kayaks, up and down a 26-foot elevation. But this infrastructure was also designed to prevent damage to the freshwater ecosystem and salmon. The locks are an important part of the region’s maritime history since 1916, and with more than a hundred thousand boats, over a million tons of transported cargo, and more than one million people visiting annually, the Ballard Locks are also an intricate mix and mingle of human life.

I wanted space to think because I had just crossed the country once again, in a move that brought me back to the Northwest. And after the disruption of a move, the clumsy orchestration of one big truckload of life to a new one, my entire studio ultimately remains packed away in storage. I lived here years ago and was forever changed by the area’s integration of life, nature, and water in its endless forms and dramatic hydrologic cycles. Though much has changed here, I feel it all anew. At the same time there is an undercurrent of feelings and new ideas that are too inchoate to process straightaway. A rich budding often emerges during travels, especially during a proper residency where the destination is designed and well equipped to produce work. Moving is very different. These are exciting changes. They are also unsettling, and render a studio practice difficult to set in motion.

This early in the morning the Ballard Locks are calm, emptied of their usual tourist buzz, but water traffic is always steady. The bells ring out urgently to the metal locking gates. “Watch your lines!” call out the Corps workers as a strange orchestration cycles through—boats and ships, lines-throwing and tying lines with the rise and fall of the water. All the while local commuters, bicyclists, and runners cross and pass. Me too. I make my way, looking down for seals and salmon near the edges and then I sit down and look at the water. After a few moments, I take out my paints. I have to think, and I need to think in colors.

When traveling, I invariably pack my old tins and a few small sable brushes. Watercolor is a medium I take seriously by others—Homer, Wyeth, O’Keeffe, and my mentor, Grace Hartigan. It’s undervalued a bit in contemporary art, but I like that. As a dark horse of art, watercolor handles like a private, immediate conceptualizer; capable of grabbing moments, laying out ideas in color. And though very difficult to command perfection—often it works better without—this water-soluble medium is extremely complex in its economy, without the pressure of finished work. Watercolors slow me down, bring me back to the wildness of materials at an intimate scale. It is intensely personal; at once vigorous and then startlingly tender. All, it seems, at the palm of the hand. Particularly, the medium’s uncertain expressiveness draws me into it. These are the properties embodying the idea of letting go. Their inherently inchoate attitude allows for the necessary sprezzatura I need begin again. But especially here.

I have been just watching the water, deep in reflection, when the all-encompassing sensation of shifting internal layers take hold. Water and its ecosystems, the mystery of unseen aquatic life: it is an all-encompassing maritime experience immediately stirring a series of deep chords. Submerged, there are immediate circumstances and memories. It seems appropriate that the freshwater separates and intermingles with the sea’s saltwater inner-workings right here. This is the undercurrent, I’m thinking, it moves on with or without me.

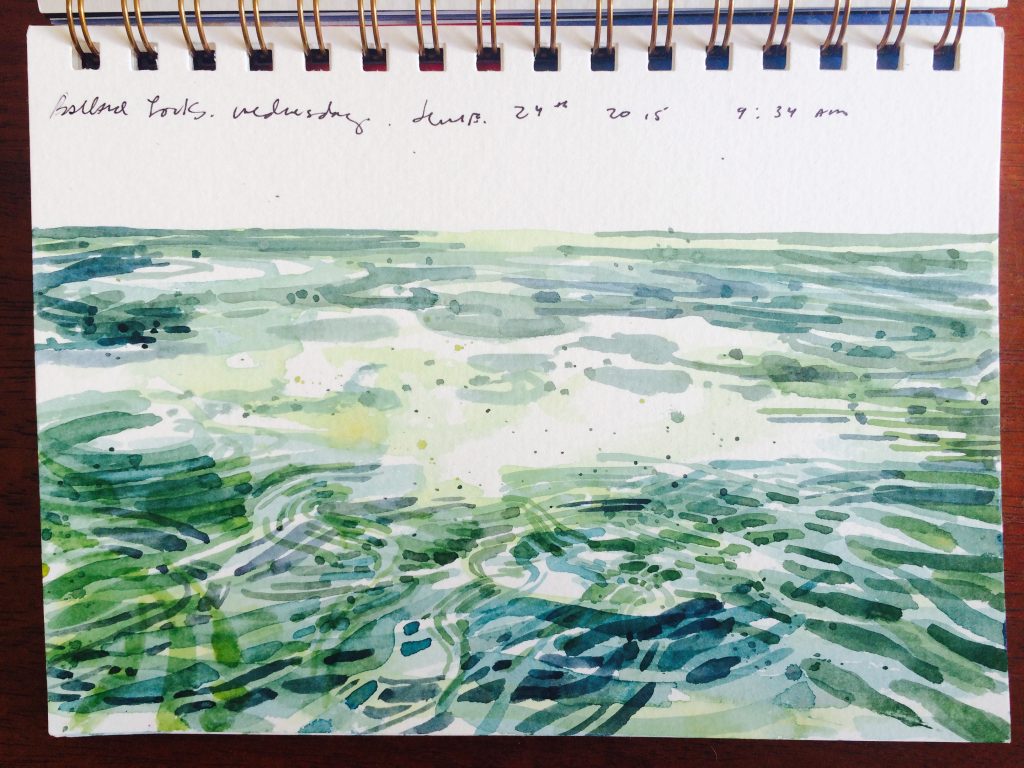

I’m stirring my tins with water. I’m laying out brushes, a rag, everything that fits into a small pack along with a few books. I peer down into the water, poised. What I’m trying to do is discover something ultimately ungraspable. I attempt, and probably fail, to orchestrate space and time in an attempt to capture the elusive lyrical nature of water, of underwater, the indifferent forms of the otherness involving disparate aquatic habitats unforeseen. It takes just one small painting and I am lost in it; lost in the rushing, forever swirling flotsam that in pale yellow rose blooms continuously curl in outwardly reaches.

When I sit up, I face the arched spillway that maintains the water level of the lakes. This is where young salmon pass safely downstream through smolt flumes. I regard the little painting I just made. It’s curiously satisfying—the first of many to come, mysteriously unforeseen like the under-passing aquatic life. On the opposite side of the locks there is a twenty-one step Fish Ladder. This ingenious system allows safe passage around the locks for the arduous migratory journey of spawning salmon. Adult salmon swim from the ocean to the tributary streams. They pass around the locks and continue to Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish. It seems they are always on the move. Pacific salmon hatch in freshwater rivers, streams, and lakes before migrating seaward as smolts. At the end of their life they return to fresh water to lay their eggs, and the cycle begins again.

I understand the time it takes to throw oneself, heart and soul, back into the flow of a healthy studio practice. In coaxing a habit of work, I have returned to the unique vocabulary of watercolor: painting backwards, transparency, effusive blending, and embracing expressive coincidences. Work is a garden one needs to cultivate. It takes a concerted effort and loving commitment. It is never very easy. Otherwise, why would it be worth it?

The water is complex enough; surface tension shifts, contradictory currents pulling underneath. It’s continuously changing. As I try to understand through color, shape, implied movement, it remains evasive. What’s important in understanding water is that it takes compassion for the unseen. Often its design suggests clarity. It lets you glimpse beneath the surface, but only momentarily; the water always changes its mind. And sitting, looking deep, thinking and painting, there is much more.

A Great Blue Heron swoops low and vigilantly against the cold rushing waters, turns from slate-gray blue to burnt umber and chestnut against the green tinge of lock water. The heron lights on the southern, Magnolia side where just the other day I stood beneath a great rookery of slightly swinging nests located high above the pathway. All day long they fly overhead. Now, thirty-feet below the Fish Ladder switchback, the heron stands quieted to the edge of dark swells. The dominance of this oddly prehistoric-looking creature in its natural hunting arena is captivating. Far above, urban foot traffic teems with bicycles, buggies, runners, and gaggles of tourists. In the close water breeze the heron’s long shaggy plumage transforms into a 1920s Flapper dress. Meanwhile, behind me, the locks fill up and let out, rise and fall, and bells urgently growl. Directly to the west are indifferent forms: the Salmon Bay Bridge, a single-leaf bascule bridge, falls from its counterweighted, upward position. A train crawls through its steel through-truss and crosses the canal, carrying a large airplane fuselage that looks like slow-moving rocketship. A seaplane passes over.

The whole time I’m watching, I’m thinking: this all about the mix and mingle. Ostensibly, I’m attempting to make this small slight painting embody an actual marine ecosystem, they way it coexists with freshwater habitats, and, with us. I’m immersed in descriptive color, sudden limpidity, and the intimation of contrasting movement. I am working wetness, vastness, translucency, and the unseen spectacular natural forces. Because … perhaps there is a further level of symbolism here? Then I think, after several paintings—am I really able to coax this much of a mere watercolor?

Sometimes, when I am deeply involved in the studio, painting, I really do believe it. Right now, I am so inside its careful consideration that I am comparing human conflict to the sea, and a tidal of emotion mixes with part of human nature. I believe it. I am attentive and emotive with the only visceral response I think I really understand, through the poetic language of paint. Isn’t it true that water is the most common symbol of the unconscious? It is a lucid form, a sensory theme, that constantly fluctuates between the internal and external, the personal and the public. And it becomes a liminal set between human and non-human, physically and biologically taking us to the underworld. And the extremity of coexisting ecosystems is allegorical to the frequency of human struggle. Painting water with watercolors provides a commentary on the universality of experience and value of the recognition of this tolerance. Empathizing with water by being mindful to look close is metaphysical and transformative. However, I’m an artist, not a scientist. I’m not positing how environments are held together–though I can’t tell you how often I feel I am a scientist of some sort, asking what can be obtained from intensive observation and emotive expression!

What begins as an intimate exploration of the actions of water and aquatic life emerges as the relentless forces of reality, both man-made and marine, through the daily practice of beginning again. What this entails is the allegory of exhaustion, the resultant and lucky unreliability of perception, and a willing embrace of continuous uncertainty. As I paint, I’m discovering something new. It’s both an intensive environmental dispatch of the mix and mingle of fresh water and the salty sea, while also an immersive interchange of nature within the trajectories of the human sphere.

Once, years ago, I abashedly allowed my mentor, Ab-Ex Painter, Grace Hartigan, to have a look at some of my watercolor ideas. She scoffed at them and said, “Do what I do, Rob, take them in the shower with you.”