The year 2015 marks a half-century of diplomatic relations between Israel and Germany. It is a complicated relationship, to say the least. On the one hand, ties between these two countries are incredibly strong; as a recent article in Ha’aretz details, Germany has made key contributions to Israel’s economy, security, and diplomacy nearly since the founding of the Israeli state in 1948. And present day relations have little of the hand-wringing and public back-and-forth that marks, say, Israeli comments about Jewish life in France, or the regular Israel-bashing that is a feature of discourse in many European countries. On the other hand, it’s Israel and Germany. There will always be a lot to say.

Literature has been a regular exchange point for these discussions for about as long as these diplomatic relations have existed, a place for the complex undercurrent to be explored. One of the repercussions of the war seems to be that Israelis and Germans are particularly attuned to what one says about the other—the discourse is heard loudly, though not always cleanly. There seems to be a need to address the other directly, if just to acknowledge how difficult that act is. In “The Holocaust Carrier Pigeon,” published in Die Zeit on the eve of a very different anniversary—fifty years after the liberation of Auschwitz—Israeli novelist David Grossman comments, “It’s not easy for me to address the German reader about the Holocaust. I almost always feel as if I am not saying exactly what I am trying to say. There’s always some slight distortion, either of excess caution or its opposite, overstatement.”

Grossman belongs to a particular Israeli generation. “I was born and raised in Jerusalem,” he said to a German audience at the 2007 International Literature Festival Berlin, “in a neighborhood and in a family in which people could not even utter the word Germany.” Grossman was raised during a brutal period of relative silence in both countries lasting years after the war ended. While there were always a few writers and artists in each country who could imagine what Grossman calls over there–the mystified space in which Jews suffered horrors and about which the new Israeli nation spoke little. But they were few and the notion of Germans and Israelis reaching out to each other was far from a priority for cultural institutions in either country.

A series of events in the 1960s opened up discourse around Germany and Israel in a new way. The trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961 put the details of the Holocaust into the public sphere. The trial, broadcast worldwide, also brought Hebrew and German languages into renewed contact. German, a birth language for many Israelis but one that was shunned publicly, was heard on Israeli televisions and radios on a daily basis for the sixteen weeks that the trial proceeded. And in that same year, Israeli literature began being translated into German, after a period from 1938 to 1961 in which not a single book in Hebrew was published in German translation.

By 1990, Hebrew literature had become one of the most translated languages into German, and books from Germany in Hebrew translation had likewise become a regular presence in Israeli bookstores. Germans and Israelis spoke to each other in many ways, from politics to literature to film to in person. And as Germans began to vacation in Israel (with, as all Israelis know, a particular affinity for the Dead Sea), Israelis made their way back to Germany for work and travel (some Holocaust-inspired, some not).

In all this proliferation and exchange, something unusual happened: the story coalesced. Our assumption is that as more people are able to write about a particular narrative, that narrative becomes more complicated. More voices, more perspectives. But for contemporary Israelis and Germans there seems to be less distortion, not more.

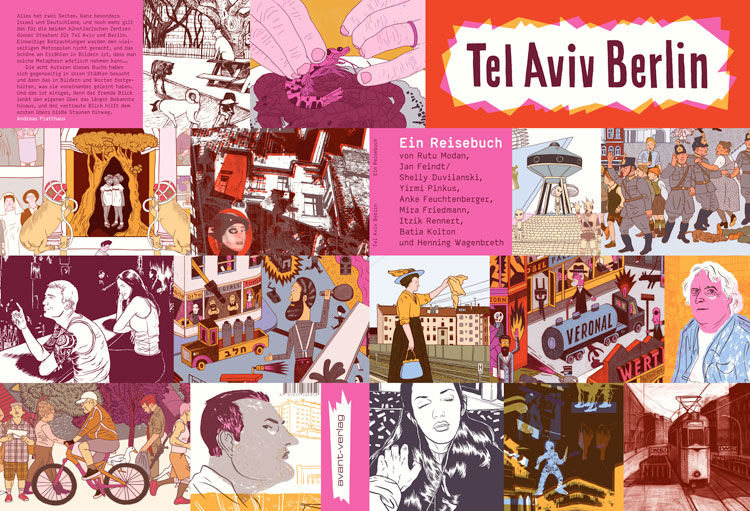

Rutu Modan, one of Israel’s leading graphic novelists, has been involved in several collaborative projects with German comics artists, including Cargo and Tel Aviv-Berlin: A Cartoon Guide. Modan says, “When I meet people from Germany … we have more or less the same story. We have an agreement about who is the victim, who is the oppressor, who is the bad guy, who is the good guy. There is a general agreement that we have even before we speak about the narrative, about the story, we have the same narrative more or less. And from that starting point we can start new relations.”

This, Modan tells us, is distinct from the narrative in other European countries. Her graphic novel The Property narrates a return to Poland by a young Israeli and her grandmother. Modan contrasts her own experience conversing with German artists with that of her experience with Poles of her generation: “With Poles, I found out that they have a different story, they don’t share the same narrative [as Israelis]. It was really difficult to accept it. I felt the urge all the time to tell the people that I was speaking with: ‘okay now I will tell you what really happened.’ But I understood that it’s impossible because how do I know what really happened? I was told a story and they were told a different story.”

Despite what Modan describes as an understood German-Israeli narrative, there are certainly still many older Israelis who remain reluctant to embrace Germany. Graphic novelist Miriam Katin is one example. Born in 1942, she is a child survivor of the Holocaust. Her most recent book, Letting It Go, is about her struggle to reconcile with the idea that her Israeli son wants to move to Berlin. Her apprehension is contradicted by her American husband, who studied music in Salzburg, and who understands Germany’s appeal for their son.

For some Israelis, German culture remains a source of inspiration and familial connection that predates the war. As much of Europe feels increasingly hostile to Israelis, Germany has become a place of welcome with opportunities to grow creatively.

Merav Salomon is an Israeli illustrator whose family emigrated to then-Palestine from Berlin in the 1930s. As a young Israeli, she has traveled back to Germany several times and set a number of recent drawings in Berlin. Speaking at this year’s Leipzig Book Fair, which featured a number of Israeli and German authors in conversation, she says, “The bond [with German culture] is stronger than the trauma of the Holocaust.”

*

*David Grossman’s comments to the International Literature Festival Berlin were published as “Individual Language and Mass Language” in Writing in the Dark: Essays on Literature and Politics. Rutu Modan’s comments appear in an interview with Molly A. Johanson, included in One Big Cemetery: Jewish History and Memory in the Comics of Rutu Modan. Cover image from Tel Aviv-Berlin: A Cartoon Guide.

Image: Cover of “Tel Aviv-Berlin: A Cartoon Guide” (2010).