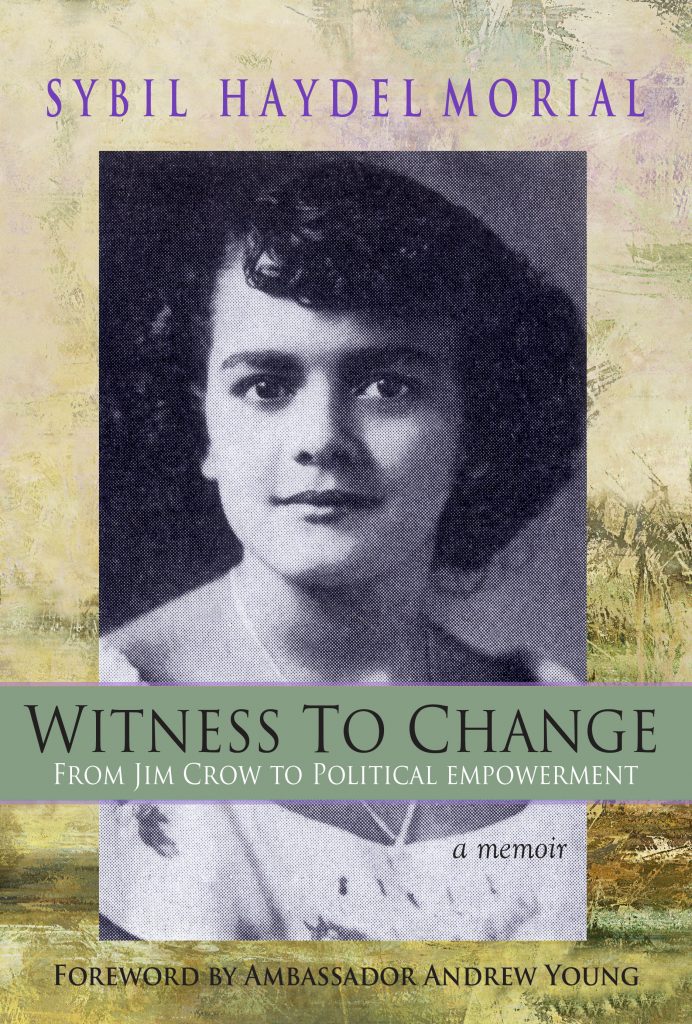

There are memoirs—internal, divulgent, and often confessional—and then there are autobiographical accounts of history. Debut author Sybil Haydel Morial’s Witness to Change: From Jim Crow to Political Empowerment (John F. Blair Publisher, October 2015), employs these alternating forms deftly, ultimately evading classification.

The Jim Crow South serves as backdrop to the author’s childhood in an African-American household in New Orleans. But as the book opens, we hear more about Morial’s school memories, of the singular tastes and aromas of Nola, and of her close relationship with her sister, Jean—a young woman suffering from a mysterious and ultimately fatal genetic condition. The personal becomes political as Morial accounts her horizon-broadening college years in Boston, as well as her experience of falling for the late Ernest Nathan “Dutch” Morial, an activist lawyer who in 1978 went on to become the first black mayor of New Orleans.

A compassionate storyteller, Morial’s story focuses on the Civil Rights Movement specifically as it affected New Orleans. As a child, she notices the irony of being a member of the black professional class, an experience marked by lavish debut rituals and intellectual pursuits, in a city besieged by the insults of Jim Crow. Later, she tests Brown v. Board of Education by unsuccessfully attempting to enroll in graduate programs at Tulane and Loyola. As a young mother and public school teacher, she writes of pursuing activism “from the sidelines,” rallying women’s organizations to register disenfranchised Negroes. As a teacher and university admin, she founds Louisiana-based civil liberties projects, and fights for affordable housing. As the first lady of New Orleans, she travels to Liberia to investigate the slave trade underscoring her ancestry. Later, she helps create the Afro-American Pavilion for 1984’s Louisiana World Exposition, and she produces a documentary about the state’s Civil Rights Movement. After her husband’s death, Sybil Morial herself is asked to run for mayor, an opportunity she declines, preferring to continue her personal work on selected causes.

Throughout the book, Morial’s observations stem from thoughtfulness. Her tone strikes the gentler side of rightful indignation. She navigates scenes and time at a brisk pace, weaving civic and intellectual insights in with sweet stories about her five children—one of whom, Marc Morial, served as mayor of New Orleans from 1994 to 2002, and currently presides over the National Urban League. Throughout her book, Morial revisits charged moments—from Martin Luther King Jr.’s very first sermon, to NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers’ murder in Mississippi, to Hurricane Katrina—that have defined not only her own life, but that of the nation’s black community.

In the wake of yet another tragic display of anti-black racism—the June 17 massacre of nine African-Americans at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church—it feels more necessary than ever to trace our steps through the history of this nation, a place so progressive yet simultaneously oppressive. Reading Witness to Change provided me with a fuller and more nuanced understanding of America’s evolution of laws and attitudes regarding race. To compound that, I recently had the pleasure of an illuminating phone conversation with Sybil Haydel Morial herself about writing, race, and current events.

*

You were 72 years old when you started writing this book. What ultimately inspired you to put your story to paper?

You were 72 years old when you started writing this book. What ultimately inspired you to put your story to paper?

Two months before Katrina struck New Orleans, I had retired from a 28-year career as a university administrator. My home was entirely flooded during the storm, so I evacuated to Baton Rouge, where I had a daughter and grandchildren. After three weeks, when the water finally went down, my house was devastated, my neighborhood deserted. I was jobless and removed from my place of comfort, and I had lost so many photos and memorabilia from my marriage and my youth. So in an effort to conjure and preserve those memories, I started to write them down—that was the genesis of this memoir. I eventually enrolled in an evening memoir course at LSU, which taught me to actually be introspective. I’m very private, so it was hard to bare all. But I had a teacher who helped to go back in time within my memory and get the details right—she’d say, “Go back and place yourself there. What did you see? What did you smell?” As I went along over the past five years, my memory improved, along with my writing; in fact, my memory started giving me more precise info!

Did any other memoirs function as models for this project?

Yes—Katherine Graham’s Washington, and Unbowed: A Memoir, by Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai, a Kenyan feminist who helped reforest her country and founded the Green Belt Movement. I read both after Katrina struck, and they encouraged me to put down my story, too. But I had no idea at the time that my memories would turn into a book—I was just recalling my story for my own comfort, and for my children and grandchildren. It was a way to soften the trauma of displacement.

It’s interesting that your book seems to be among the first accounts of the Civil Rights Movement as it took place in New Orleans. Why do you think Nola’s movement history has been so relatively under-the-radar?

Because it wasn’t as publicly violent as it was in places like Birmingham, Selma, Atlanta, and other Southern cities. Nola is a little more laid-back. There were rough things that went on—we had our share of beatings and unjust arrests—but they weren’t as cruel as cattle prods and such. It was other, far more violent cities that attracted media attention.

You write about producing a well-known documentary, in 1987, about Louisiana’s Civil Rights battle. How did creating A House Divided compare to the process of writing this book?

When I produced the documentary, I was an associate dean at a school in New Orleans, and thus able to work with its resources and personnel. So that was completely different from writing the book. Aside from talking to my LSU teacher June English, who I call my “book consultant,” and my children—I’d call on them to help refresh my memory—I wrote it alone. I had to stay motivated. Luckily, everything kept evolving, and getting more interesting and appealing to me. In a sense, a memoir lets you relive it all over again—the good, as well the bad.

Your story’s also peppered with overarching insights pertaining to African-American and Civil Rights history—it’s rife with specific facts about the Jim Crow years. That couldn’t all have come from memory—what was your research process like?

I did a lot of Googling for dates and names, and a lot of old-fashioned research to confirm my own memories. My husband’s papers are all at the Amistad Research Center at Tulane, and I’ve sat on their board since 1970. So I would go there to verify whatever my memory was telling me. I also spent a lot of time in the Louisiana Archives at the New Orleans Public Library.

Who’s your target audience? What effect do you hope this book has on its readers?

I think not enough people are writing about the Civil Rights Movement—those who lived through it are passing on, and many of them did not document their stories. But one person’s involvement in a period is just as important as an overarching history—I think there needs to be more of that. It encourages individuals to be courageous and work to correct what’s wrong in their countries, their lives. I think curious students and history buffs will read it, but above all, I hope it will empower African-Americans and women.

In the book, you note that the “Black is Beautiful” consciousness of the sixties and seventies helped you and many others to free yourselves from self-denigration. How do you feel about today’s semi-counterpart—the #blacklivesmatter hashtag?

I think the theme is recurring. Again, we have to reassess what we are, that we have value, that we’re deserving of life, and that we’re beautiful—that we don’t want to be anybody else. And #blacklivesmatter is so important because after sixty years, the shadow of Jim Crow has come back. We’re struggling to be equal, to be viewed as equal citizens.

You write about how, early on in your husband Dutch’s political career, in 1967, he gets arrested for loitering—for loitering in front of his own house, in fact—and becomes vocal about the ways in which racial profiling and police brutality plague the black community. Can you talk about Dutch’s legacy as it relates to the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and Freddie Gray?

My husband was fearless. He would’ve spoken out about each of these tragedies—he used to be known for saying things that other people wouldn’t’ve dared say, because they’d have wanted to protect their turf. But not Dutch—he was used to being a target of violence, and he would have a lot to say about what’s going on in America today.

What would Dutch have to say about this month’s tragic massacre in Charleston’s AME Church? And is there anything you want to say about it?

That it was definitely a hate crime. That it’s of grave concern because in recent years this type of thing has been happening way too often, and that it’s something that society is going to have to deal with. Because the more this type of thing happens, the more emboldened some people are going to be to continue reacting this way. The challenges of racial justice are in many ways the same as they were fifty years ago—the shadow of Jim Crow still hovers. The law is now on our side, but attitudes haven’t changed. You can change the law, but you cannot change hearts and attitudes—there’s still a lot of resentment and intolerance. I think white people today are getting subliminal racist messages—they’re conveying behind-the-scenes beliefs about the separateness and inferiority of African-Americans to their children and friends. I recently heard a white child call a black child jigaboo, and you know what the white child’s mother said to him? She said, “You can’t say that here. Only at home.” What kind of mixed message is that? Somehow, we have to get to the core of this resentment. I would be so pleased if my story would get people to think about how we can do that in the present—if it would get people talking about that, and trying to break down what’s happening. Also, it’s got to be an open conversation between whites and blacks. Because it’s the small actions that result from these types of conversations—for instance, Wal-Mart and other retailers’ decision to get rid of all Confederate materials—that shows that we, as residents of the United States, all have responsibilities and commitments.

*

Witness to Change is available for pre-order through John F. Blair, Publisher.