Many environmentalist-minded readers believe the nature writer of today’s turbulent, climate-changing times should function as both artist and activist. If David Gessner’s All the Wild That Remains (Norton, April 2015) is any indicator, the modern nature writer indeed should embody both roles—and could even expand his or her repertoire and master memoir, essay, biography, travelogue, and/or literary criticism.

Via these and more seamlessly braided forms, Gessner’s book calls readers to action, inspiring outdoors-appreciating-yet-non-activist readers like myself, for instance, to question our own sense of place in this world. The author of Sick of Nature, Return of the Osprey, and Soaring with Fidel, among other gonzo-reminiscent narratives that subvert the traditional constraints of nature writing, Gessner has an uncanny ability to make nature matter to the laypeople among us—the science phobes, the less than adventurous, the “indoor cats.” He does this, simply, by getting personal with us, causing us to consider the state and the fate of the places that matter to us.

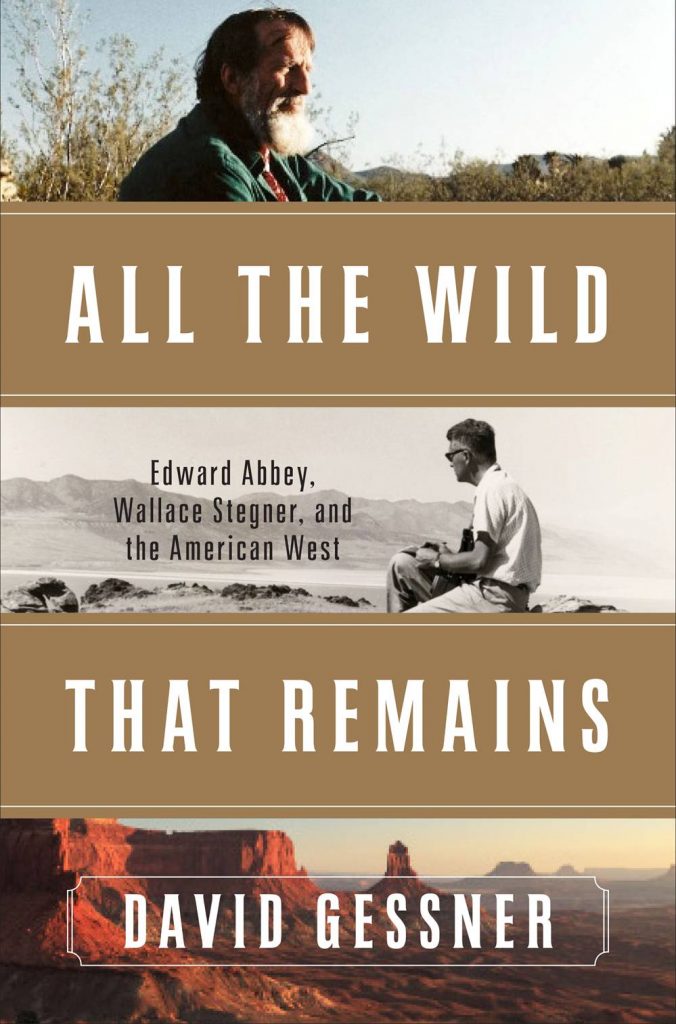

In addition to upending orthodox notions of form in All the Wild That Remains, Gessner road-trips to the deserts and canyons of Colorado, Canada, California, and Utah. Along the way, he dissects the lives and works of his two heroes: Western environmental writing giants Wallace Stegner, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and buttoned-up environmental activist, and Edward Abbey, hard-living writer, rogue eco-terrorist and impetus for Earth First!—and as it turns out, perfect literary foil for Stegner.

While Stegner worked within the system, lobbying legislators to effect environmental change, anarchist Abbey sought to disturb the system, to take matters of interrupting industrial development into his own hands. But what did link the late Stegner and Abbey was their echoing cautionary cry concerning the aridity of the West, the fallacy of the myth of the rugged, individualistic American frontier. Both men were vocal about their fears that an increasingly populous and thirsty Western populace would eventually ravage the region’s natural supplies.

All the Wild That Remains, as it happens, was released in the West’s fourth year of drought, during a year when the Sierra Nevada snowpack set record lows. In short, it arrived during a time when Stegner’s direst predictions about the un-sustainability of life in the water-deprived West seem to be coming home to roost.

Gessner, a native New Englander who spent a “glorious” chunk of his mid-life in Colorado, re-visits many of his beloved haunts in All the Wild That Remains. Meanwhile, he pays his heroes some literary debt in his attempt to reconcile and make sense of Stegner’s and Abbey’s diametrically opposed methods of activism. The investigative sojourn is also marked by plenty of play, and a good deal of Abbey-esque side trips and booze-fueled interviews with colorful pals and strangers. Altogether, it chronicles what was a long and intensive journey for the North Carolina-based professor, husband, and father.

Back home, Gessner typically spends the bulk of his mornings putting words to page in a self-constructed backyard shack he’s nestled into the marshlands of humid, coastal Wilmington. It’s where he’s written multiple nature books and novels, as well as countless essays, editor’s notes (he’s the founding editor of the “place-reimagining” Ecotone Journal), and blog entries.

Enter the wood-paneled workspace, littered with dog-eared books, loose pages, big windows, and empty IPA bottles, and it’s evident that the writing shack doubles as a reading shack, a beer-drinking shack, and a birding shack. Gessner’s favorite way to “break” from intensive writing sessions is to venture further into the marsh and dive into Hewlett’s Creek, an Atlantic tributary that’s home to many of the birds he likes to write about.

Yes, Gessner birthed much of this personal treatise on drought and resource depletion in a setting that’s about as water-logged as the West is dry. While the remote, dedicated writing zone can feel a little intimidating to an emerging writer like myself, the space has some refreshing, if rustic, personality to it. It conjures humor, badassery, and a touch of pathos—elements reminiscent of the energetic prose and inviting wildness of All the Wild That Remains.

It’s here where Gessner did much of his preliminary reading of Stegner’s and Abbey’s works, and where he plotted his itinerary, months-long ordeal that included stops at both men’s birthplaces (and their versions of writing shacks), a drop-in to fellow Stegner devotee, writer, and activist Wendell Berry in Kentucky, a harrowing plane ride, and plenty of canyonland mountain biking.

As a nonfictioneer, and also as a Chicago native who’s lived in drought-ravaged California and who now calls the receding coastline of North Carolina home, the book, for me, was a feast for thought. Do writers have a responsibility to provide their causes with a voice? Does regional loyalty translate to fiercer environmental activism? How do you combine biography and memoir? Can road trips be literary and fun? Recently, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Gessner on a muggy East Coast day, during a lull in his westward-ho book tour. Beer may or may not have been involved.

*

In crafting this unusual hybrid approach to biography, memoir, and travelogue, were you working with any models? How much of the content and form were intentionally structured, and to what extent was the the book a product of in-the-moment instinct?

You know, I try to make it seem offhanded, but a lot of thought went into where I was gonna thread what biographical chunks, and where I would braid moments of literary criticism, etc., beforehand. I’d say I’ve always been a personal writer who embraces memoir, but who likes to mix in chunks of essay—I’m always jumping back and forth. Then seven years ago, when I wrote Soaring with Fidel, and followed ospreys down the coast and into Cuba and Venezuela, I started embracing the road trip as a form. Then again when traveling to the Gulf of Mexico during the 2010 oil spill. So, I was familiar with all the modes that I used, but I wanted to challenge myself for book number nine. I did specifically set out to have a dueling biography, have nature writing, and have me in it—but maybe not so much me as before, because I was working with two interesting characters—and see if I could play chess on three levels.

How similar to this conception was your final product?

It was pretty close. But I worked with the caveat that openness would be built into the project. The big open factor was, ‘What’s gonna happen out west, who will I run into, who will I meet in a bar in some corner of Utah?’ For instance, I didn’t know I’d go up in a plane with a guy. Keeping spontaneity a part of the process was a big part of this project. I forget who said it, but one of my mottos is this: Good writers make outlines; great writers throw them away.

Your background is in writing and teaching, rather than science and nature. How do you manage to educate yourself on these matters to the point you can report confidently on the environmental factors triggering drought, fire, climate change, etc.?

I am happily ignorant. I go up to scientists wearing that ignorance on my sleeve. I ask questions and explain that I want them to explain their answers so idiots like me can understand. Since Osprey, I’ve also gotten pretty good at reading science, and putting it into vivid language. I like the idea of taking arcane things, and making them really physical and immediate—that’s a fun challenge for me. So I enjoyed incorporating scientific insights into this writerly book about writers.

It’s abundantly clear how both Stegner and Abbey influenced you as a writer. How about as an environmental activist?

The big challenge for me has always been that I move around a lot—Cape Cod, Colorado, North Carolina—and it’s a little harder to say, ‘I’m gonna fight for my home!’ when my home keeps shifting. But reading these guys makes me feel like it’s time to put up or shut up, that I need to fight for all the areas I love. I’m going to try to push here to work with Duke geologists on coastal overdevelopment, and to get involved with the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, and I’m going to continue to work with Cape Cod committees focused on preserving [nature writer] John Hayes’s house. So I’m essentially going to try to use my multi-regionalism to my advantage. What’s also personally inspiring is the fact that Stegner and Abbey were both committed writers, and Stegner at least was a busy teacher, too. And yet they both spent considerable time being activists. It’s shown me that there’s no excuse; I’m not off the hook because I’m busy. Fighting for the earth should be a huge priority in there, even if it means eventually bagging teaching.

When you meet with the consummate Kentuckian Wendell Berry early in the book, you two meditate on the idea of displacement vs. ‘being placed,’ or securely rooted, in literature. Can you talk about your on-the-road writing process? How does that experience compare to sessions in your shack here in the East?

As I get older, the more I come to believe that you don’t have to be Wendell Berry or Thoreau or any super settled person to write about place. I do a lot of writing elsewhere. When I’m in the mountains of Colorado, for instance, I’m inspired, and the words come directly from the land. I like to think I’ve made virtue out of necessity—I keep getting the rug pulled out from underneath me when it comes to placement, and in that way I’m like a lot of humans. But you can still love place and write about place without being from one place; that’s kind of what this book is about. I mean it’s exciting that there are so many places that can stimulate us still in this overdeveloped country, this overdeveloped world.

You note in the book that compared to some of your other trips out West, the average person you encountered during this journey seemed to be more accepting and aware of climate change. As people increasingly accept this phenomenon as truth, do you think it will show up in more forms of literature?

I do think so—and not just in science fiction and nature writing. I took a trip to New York after Sandy to meet with geologists, and they said something I keep noticing: the regular population is ahead of what we’re seeing on the news. People get it; the weather’s freaky. Here, we have sea-level rise, and in the Southwest, what was dry before is becoming drier. People see that this is a fact. And that’s where Stegner comes into play—he always said, ‘You can have your myth of the fertile, prosperous west, but here’s the fragile reality—it’s a dry, dry land, so treat it like that. Let’s not pretend it’s something it’s not.’ And the reality is apparent now—climate change is a thing. But it doesn’t spell out complete retreat, doesn’t mean that the world is doomed, just that it’s changing. And even if it is doomed, there’s a lot of beauty and wellness that’s still in the world. To not acknowledge that science is historically consistent with what people have long done in the west, but it’s getting more and more clearly preposterous.

Perhaps that’s why your book tour is so westward-bound right now? Do you have a different approach for promoting this book in the East, to readers who may not have even heard of Stegner and Abbey?

Everything in this book applies to us here in the East, where we’re experiencing coastal erosion and sea-level rise and horrible storms and floods for all the same reasons the West is drying out. I’m working according to a kind of venereous strategy of winning the hinterlands, and then heading east. It’s always kind of funny to me how the West doesn’t get the East, but it’s really funny how the East doesn’t get the West. So the plan is, hit the West first, build support, and then attack the East. One of the fun challenges of the book, for me, was using those Stegnerian techniques of connecting the dots and connecting climate to the ways we use land and water. Something I can talk about in the East is what we do when a hurricane blows through. We yell, ‘Rebuild, rebuild!’ like it’s this patriotic thing. But it’s the same concern as the houses that burn in the foothills of the mountains of Colorado. It’s a universal issue of our right to use fragile land.

In the book, you lament that you never got to meet either of the two late writers. Pretend for a moment that they come back from the dead for a day, and that you get to plan some sort of reception for each.

Stegner and Abbey would both intimidate the hell out of me, but in different ways. Abbey as a legend, as a character, would be so intense. I’m going to speak tomorrow night in Salt Lake City, and Ken Sanders, owner of Ken Sanders Rare Books, does a mean impression of Abbey. One area where he and I could connect, however, is through alcohol. We both are on very familiar terms with it. So that would be good. Stegner’s intimidation would be of a different sort—he’s just an intellectual giant. But I feel like I would be in a better position to communicate with him now rather than twenty years ago, when I first discovered and starting reading his books. So I’d probably bring Stegner down to the shack and try to get him going, and hopefully ultimately convince him that I’m not a complete idiot. If we couldn’t parry back and forth, I’d at least try to listen intelligently. With Abbey, though, it’d have to be a day of drinking and hiking.

*

All the Wild That Remains is available for purchase through amazon.com and W.W. North & Company. For more information on David Gessner’s current and upcoming projects, visit his author site.