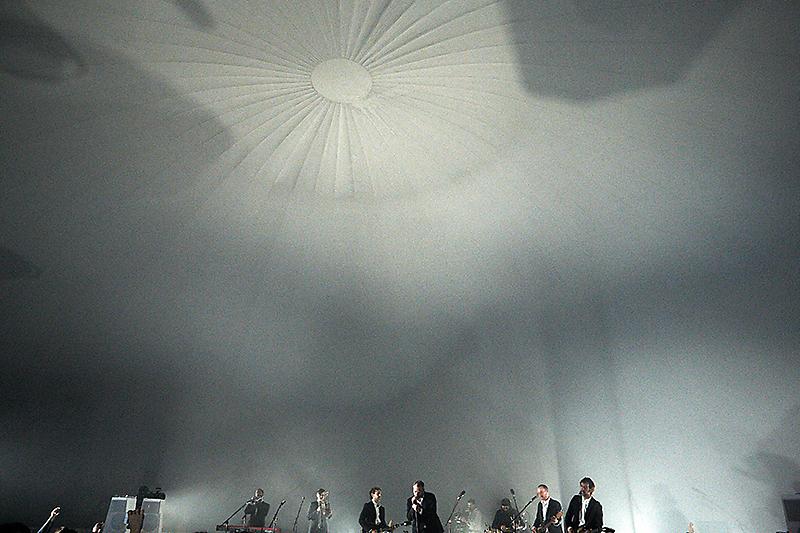

On March 5, 2013, in a sparse room of MoMA PS1, atop a perpetually foggy stage and standing before a packed crowd of predominantly white hipster 20-and-30-somethings, The National played their song “Sorrow” 105 consecutive times in a performance lasting over six straight hours. This was not their idea, but rather was conceived by artist Ragnar Kjartansson as a “durational performance” entitled A Lot of Sorrow, which continued his exploration of repetitive performance as creating a “sculptural presence within sound.” Played without irony, the indie-pop song’s repetition pinged from sad to comical over the hours, maddening to hypnotizing. Matt Berninger, the lead singer and songwriter, sometimes openly wept as he crooned the song’s beginning, “Sorrow found me when I was young, sorrow waited, sorrow won,” only to joke hours later at the performance’s closing, “We got one more song for you guys, this one’s called, ‘Sorrow.’”

I wasn’t there. Instead, I had just received my MFA and was beginning a year-long writing fellowship, which was intended to be an unstructured bundle of funded time spent chipping away at your writing project. That’s what it is for some people. For others, like me, it’s a harrowing assault on your headspace, and, perhaps not unrelated, your weight and television binge watching habits. At the fellowship year’s commencement in early May, around the time Berninger was howling about his sorrow and just before The National released Trouble Will Find Me, their sixth studio album, I was taking a break after working furiously to hand in both my thesis and my own students’ final grades.

Everything was suddenly excellent: the days before me were lush and filled with hours, my bank account had money magically deposited into it, coffee was enjoyed in air-conditioned rooms and sipped in luxurious slow-motion. I eventually got to writing again, and although the year brought me some of my best writing and intense realizations about my novel and myself as a writer, like when I work best (2-4 PM or 1-3 AM), what I require to be most productive (a green notebook, black pen, window with a view, meticulously clean apartment, pausable music, popcorn), what authors make me jealous in the best ways (Aleksandor Hemon), what television shows are inspiring (The Sopranos), comforting (King of the Hill), and best-midday-nap-of-your-life inducing (oddly The X-Files, except for that incest episode and that Russian toxic toilet monster episode–those were fucked up), I also fell into a deep, lingering depression that is still reemerging in new ways, the cold you’re positive has finally fled only for you to wake up more hoarse than ever, making everyone hug the walls in avoidance of your germy breath. So I guess Trouble Will Find Me becoming the album I most frequently returned to throughout this fellowship year isn’t all that surprising.

I was admittedly a melancholy kid during high school, but writing was always there as my most trusted outlet–I started a creative writing club, was the only student who knew the school had a literary magazine let alone felt compelled to submit, and even traveled during a summer vacation to a young writers program in the boring landscape of Gambier, Ohio, my new geeky comrades mystified not so much with my words as with my New Jersey accent. Around then is when I transitioned wholeheartedly from bands like Dave Matthews Band to Radiohead, telling friends, No, man, that stuff was cheesy, this stuff is the soundtrack of my dreams. I went off to a small college in the Lehigh Valley where I lived with Dead Heads, one of whom, upon entering my room while I listened to Tom Waits’ “Goin’ Out West,” stopped dead in his tracks, face ripe with concern, and asked me, “Wait, you listen to this, like, as music?” I was working on a creative thesis then, too. I was happy, or, I now recognize it as a time when I should’ve been happy and probably wasn’t but my unhappiness didn’t stop me from having an okay time.

Though I loved blasting a good Waits ballad, his voice was too gravelly to imitate, so I slipped into bands with more bassy baritone singers, ones I could unabashedly sing along with and not feel too self-conscious about where our voices’ pitches didn’t coincide, like Morphine’s Mark Sandman, his low, slow voice a proxy for my anger, wannabe mystery, and ill-conceived seductions, and The National’s Matt Berninger, for my anxiety, paranoia, ennui, sarcasm. I fell into what I now recognize was the early twenties Self-Pity-Party: living in perpetual boo-hoo-ness as I went to my good job, drank with my best friends, and came home to a rare apartment not infected with bed bugs, all while always managing to feel sorry for myself, fueled on by tracks like “Mistaken for Strangers,” where Berninger epitomized the feeling and how ridiculous you feel for feeling it with lyrics like, “you don’t mind seeing yourself in a picture / as long as you look far away, as long as you look removed,” or lamenting in “Secret Meeting,” “Didn’t anybody tell you how to gracefully disappear in a room?”

I was still writing, workshopping with strangers in an editor’s West Village apartment once a week, but growing more and more disillusioned with writing as my life choice, frustrated at how I could rarely finish what I started, and even if I did, how I couldn’t get my stories into The New Yorker or some equally unrealistic magazine. And to write a novel someday? Are you fucking kidding me? My boss at work, whom I loved, was also fired, and then I was promoted into her role, an intimidating new boss suddenly lording over me, making “Baby, We’ll Be Fine,” my new anthem for nightly anxiety: “All night I lay on my pillow and pray / for my boss to stop me in the hallway / lay my head on his shoulder and say / ‘Son, I’ve been hearing good things.’” A full depression had bloomed making me feel like Houdini perpetually trapped in the second act of a magic trick: I’m underwater, upside down, always wrapped in chains, when will I be able to say, “Tuh-dah!”

Around this time, The National released High Violet, the album I consider to be their dark-and-stormiest, either because the Dessner brothers’ guitaring is more muddled, because Berninger’s lyrics, even equipped with his token self-deprecation, are still poignantly sad, or just because I was at my most depressed and everything around me seemed infected with sorrow. I often walked home “through the Manhattan valleys of the dead,” weeping in front of strangers while I crossed the Queensboro Bridge, connecting with lyrics like, “With my shiny new star-spangled tennis shoes on / I’m afraid of everyone.” I, like Berninger, now “live[d] in a city sorrow built.” I’d stop and look to the East River where my grandfather, who emigrated from Italy under strange and terrible circumstances, who almost died of tuberculosis, who helped raise three kids on a janitor’s salary, swam when he was a boy. And me? This privileged, tennis-shoed asshole with health insurance who occasionally splurged on inane bottomless mimosa brunches and J. Crew button-downs was sad? What right did I have to be depressed?

There is, of course, nothing worse for depression than telling yourself you don’t deserve to have it. That’s just putting a coat on top of a coat; you’ll eventually overheat. But this sadness, the car crash right in the middle of my brain’s road, was oddly motivating: having such an ugly thing to inspect helped me write more, helped me sneak into the office during our Christmas break to work on MFA applications, revise for hours at home, tell friends I was going through something and maybe needed to get out of the city. I got in to a great program, moved to Michigan, figured out the book I was writing and worked hard on it, and things were spectacular. Until they weren’t.

There is, of course, nothing worse for depression than telling yourself you don’t deserve to have it. That’s just putting a coat on top of a coat; you’ll eventually overheat. But this sadness, the car crash right in the middle of my brain’s road, was oddly motivating: having such an ugly thing to inspect helped me write more, helped me sneak into the office during our Christmas break to work on MFA applications, revise for hours at home, tell friends I was going through something and maybe needed to get out of the city. I got in to a great program, moved to Michigan, figured out the book I was writing and worked hard on it, and things were spectacular. Until they weren’t.

Trouble found me again in the form of that paid trip through purgatory, otherwise known as a fellowship year. My abruptly moving back to New York and working long days while also attempting to stay after-hours and get some writing done has helped, but not much. Writing this novel has ultimately felt like I’m on my own stage wailing the same song into incoherence for hours and days and months and years on end with some fans rooting me on while others stand idly by, asking, “What are you doing that for?” I’m going through something again, that’s for sure. But like Berninger’s lyrics throughout Trouble Will Find Me, I’m equipped with a better sense of humor about it, knowing I’ll be able to joke with everybody when I’m done: “You didn’t see me, I was falling apart / I was a white girl in a crowd of white girls in a park / You didn’t see me, I was falling apart / I was a television version of a person with a broken heart.”