In January, I shared with regular readers of this blog my experience reading as many editions of Moby-Dick as I could get my hands on in a small university town. I found fancy illustrated versions, and even fancier illustrated versions, and modest versions for the 1930s Everyman, and versions that had been subjected to undergraduate scribblings, and even a children’s pop-up version—albeit one so intricately cut and lovely that you would cringe to see a toddler’s hands pulling on its riggings and sails.

Each edition different from the next, in its own distinctive way. And yet, they each share one thing in common. None of them know how to speak Hebrew.

This failing, minor perhaps, comes up in the very beginning of Moby-Dick— even before the main text—in the “Etymology” section. “Etymology” is already an odd part of the book, shifted to the back in some editions, discarded altogether in others. It is credited as the work of a “Late Consumptive Usher,” and is followed by another occasionally omitted chapter, “Extracts,” attributed to a figure called the “Sub-Sub-Librarian.” Melville scholar Athanasius C. Christodoulou (whose lengthy name is not, apparently, an alter ego of its own) is one of the few academics to focus on these introductory sections. He writes that Melville, “Placed ‘Etymology’ and ‘Extracts’ at the opening of his novel for two reasons: to indicate indirectly the main theme of the work and to give, indirectly as well, some basic instructions to readers about how they must read the book in order to conceive its deeper meaning.” With so much indirectness and indirection, it’s no wonder that many readers choose not to engage too deeply in these chapters, and bustle ahead to meet Ishmael as quickly as possible.

Still, for me, “Etymology” is fascinating, mostly because a) I am admittedly a word nerd, and b) the chapter consists almost entirely of an eccentric list of foreign words for whale, one that includes Latin, Anglo-Saxon, Swedish, Icelandic, and Fegee [sic], among others. Of this world-spanning list of languages, Melville chose to start with Hebrew, the word חן.

But wait. These letters, which form the Hebrew word Ḥen, do not mean whale at all. Hen is a Biblical word that translates as grace or charm (and is sometimes used as a name in Israel and elsewhere). So what is going on here?

Theories abound. It took twenty-three years to produce the Northwestern University Press/Newberry Library standard edition of Moby-Dick, and among the thousands of textual decisions the editors had to make, one that occurred just before publication was how to handle this mixed-up Hebrew. The editors finally decided to attribute to Melville a mixture of intention and error, and changed the Hebrew to תן. This means jackal, but the editors believed Melville intended it as a version of the Hebrew word for crocodile, based on the author’s reading of a common reference work of the time, James Kitto’s Biblical Cyclopedia.

Neil Schleifer, in the pages of the Melville Society’s Extracts, takes a rather more Talmudic view of Melville’s authorship, deciding that there can be no error in the text, only meaning yet to be uncovered. Based on, among other things, his numerological reading of Hebrew, Schleifer suggests that Melville knew what he was doing all along, and was making a complex reference to grace that carries through the book.

For my part, I am interested less in Melville’s intentions than in how his Hebrew has been treated in subsequent editions. Or mistreated, we might say. The simple version: it’s a butcher job, folks. The Modern Library edition? תר. That gorgeous Lakeside Press edition I mentioned in the earlier essay? חך. The fabulously expensive, meticulously printed Arion Press version? חד. A 1923 version? חו. A 1943 version? תר again. See the differences? If so, you can follow the trail of nonsense, the error in the code, like a staticky game of Hebrew telephone. If you can’t see it, well, you have a lot in common with the printers of these volumes.

It is striking how a dot of ink in one direction or another, invisible to so many readers, can mean so much to others. For thousands of people each day, the Hebrew alphabet is invested with layers and layers of meaning—denotative, connotative, mythical, mystical, narrative, numerological. Yeshiva students can spend hours dissecting the implications of a Hebrew letter; artists and writers create stunning books around the alef-bet; even vocalizing how a Hebrew letter can be, in certain rooms around the world, rich with implication. (See this recent performance by Israeli vocalist Victoria Hanna, the daughter of an Egyptian rabbi, to see Hebrew pronunciation explode into Kabbalistic-linguistic art). And yet it shows up in one of American literature’s most revered books as little more than a printer error. Even in a world of globalization, of the meshing of cultures (and sometimes the overwriting of one culture by another), we retain distinct pockets of ownership and meaning.

Or do we? The world of reading Hebrew that is beyond mere language—the culture of Torah study— has much in common with the way that Melville scholars relate to Moby-Dick: the hours of intense study, the pilpul over interpretations, the preferences for certain commentaries over others, the core belief that there are certain books that, no matter how many times we read them, will always give us more.

They intersect only for a moment, these intensely learned worlds, right there at the beginning of Moby-Dick. And then we are on to the next word: whale, in Greek.

Which, by the way, the Northwestern-Newberry editors also saw fit to correct. Cue the scholars of Greek.

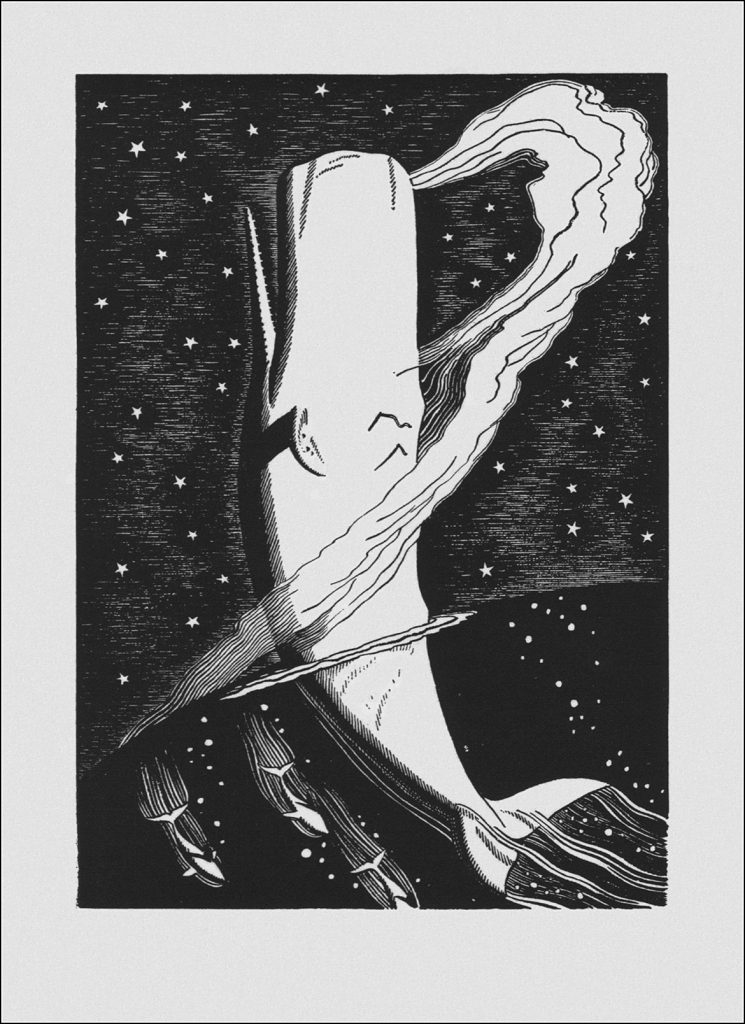

Illustration by Rockwell Kent.

*Thanks again to Miriam Intrator and the Robert E. and Jean R. Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections at Ohio University Libraries.