I like to think of drawing in Martin Heidegger’s use of the Greek term poiesis, or the process of the thing blossoming out of itself like the opening of a flower bud—or, even more pointedly, like the melting of a frozen body of water and the ensuing rush of waterfall. Poiesis is the process by which burgeoning creativity passes a threshold and is quickly released into fruition.

In the studio right now there are a few unfinished canvases leaning against the wall. Through the windows, the west Michigan snow has been falling on and off for the past few days. Every time I shovel the walk, a few hours later it has filled up again, leaving only a trace of my boot prints and shovel scuff. In front of the easel, solitary, self-possessed, I am tending to the third in a series of drawings. I say “tending” because I am allowing each of them to grow without exactly understanding why or where they might take me. They are mysterious and liminal, and yet upon completion I find them as satisfying as a finished painting. Drawing is a discipline that has always been the core to my practice. In the studio, drawing is sometimes feral and filled with the thrill of uncertainty. But it is also as curative as nature itself. The process stirs the imagination and always makes me feel I have been deployed on some old-worldly scientific expedition. However transitional and fragmentary, or complete and accurate, the discipline is a universal to many different artistic outputs. In my work, drawing is inseparable to painting.

Each painting I make starts as a complete drawing on the canvas. I think of my paintings as drawings because of their continual use of line on top of the design. Conceptually, painting and drawing connect with me differently, but drawing is a parallel to the work, and not separate. Discovering drawings by artists as preliminaries to further works can be an exciting prospect like an archeological dig. Idea sketches from Louise Bourgeois, Joseph Beuys, or Wyeth; whether these are dashed off, furtive in shape and form or furious in labeling and writing (the best kind!), they feel imperative because we are able to experience the artist’s thought process. It’s especially important because we are made privy that with any work of art, from a postulation of Smithson to the emotive sketchbook of Käthe Kollwitz, it takes many errors to coax an idea into existence.

It is through these intimate works that we are able to witness the simplification of an elaborate concept because the visual language of drawing is direct and primal. It’s a visual ontological process directed from the mind, the heart, and straight to the hand. With this intimacy in mind and artists aside, some of the best drawings I have ever seen were the ones created and given to me by complete strangers in the form of directions. These are true formative works because the creator attempted to explain something with just enough visual description that in turn, something of essence is left behind. These take the form of oblique scribbles on the back of a receipt, a quickly ripped tear-shaped notebook paper containing a slopping list of directives, or a glossy sliver of magazine, blue ink in the margin, a meander of lines leading to a tiny square and a inadvertent thumbprint—each contains something pure and spontaneous. Beauty buds in the haste and the informative. Ideation should always be this concise and rewarding. Many of those maps I have kept and found again and again.

They end up intact, as a bookmark for Flaubert, or at the bottom of my bedside table drawer under loose change and a pocket knife. As urgent as the notes are made, their meaning, for the life of me, has been all but lost. They are still so compelling that one can make a painting directly from them. My own thoughts dial around their archaic symbols and half-words, the key of which had been pantomimed on a cold snowy walk or cupped into a rolled-down car window—If you see this, you will know. You can’t miss it; the catalpa tree on the left. There is a bend in the road, like this, like an elbow—all is completely lost. These thought details are the only remainders of brief intimacy.

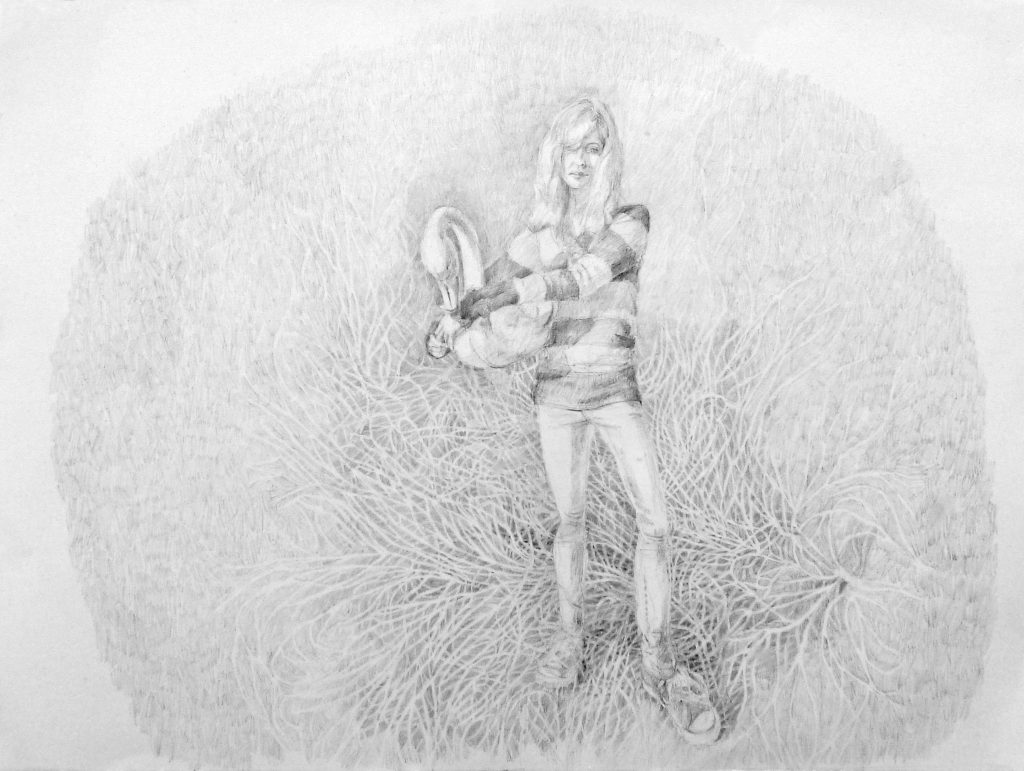

My first series of drawings came out of this. Since I was a boy, I have been obsessed and placated by the experience of nature. Because I was traveling through Spain I needed to create very small, intimate works. I was thinking of strength and fragility in nature. I felt the works needed to fit in the palm of a hand, slipped into a pocket or a wallet for a few weeks, risking wear from the passage of time. At such a small scale they were also haunting. As they developed as ideas the drawings became more intricate. Later on, in my frustration with the state of nature today, to escape into something, I begin to make larger paintings from these small works as a discourse on nature’s most vicious predators, mankind. I had to work hard to not lose the vulnerability and purity of passion the smaller drawings embodied. Before that, all the drawing I had done was surreptitiously covered up with paint, like the snow on my Michigan walk. I enjoyed that it was like a secret, that if you looked hard enough you could discover the intimacies of wild thought. A craze of charismatic concentric circles dashing off the carnation of idea, arriving obscure, sullen, recalcitrant, and foreign. This would become a simple contour of a downward-cambered rhododendron bush. Later that bush would sprout into a tree, where the ghost of the rhododendron at its foot suddenly resembled an emptying pond.

Or better, the active afterimage of a torso and leg I could not get right. Sometimes ideas can be difficult to tame. Obsessively, I reconstructed them over and over again so that movement was better captured than accurate form. All stages remain as design architecture. Stumbling awkward textures fill passages with inadvertent and useful scumble. It forms character in the work. Each painting still begins as a labor of graphite, because it is an immediate and inaccurate way of fumbling into a more sophisticated, emotional work. Tidying up isn’t necessary because subsequent layers added in the various viscosities of color material show the underneath as a trace of something true—like those once-dashed-off maps through the gracious hands of accosted strangers. As controlled as they may appear, my most recent series of drawings are very wild to me. Sometimes drawing feels like the only lucid cerebral space. A door opens to the magic when the mind is churning out ideas and there is nothing in between—kindness, forgiveness, humility. Even though creating new work should breed some new discourse, I think we should not be encumbered with such heaviness—only perfunctory notes, as a drawing practice is less about the outside as it is internal. Poiesis in drawing is harboring concepts and letting go, allowing for the bloom of the flower to unfold and form into its fully-realized self. Because later it is about discovering harmonies and mending our connections to the world incarnate.