A few years ago, I was teaching a middle school writing elective at a well-regarded summer camp for the arts. The students in this class were not primarily interested in writing: they were there as young musicians, or dancers, or studying “general arts” which usually meant their well-off parents thought it more edifying for them to draw with charcoal and write poems and create spliced-together musical theater out of the latest pop songs than to let them spend the summer watching TV and lighting matches in the backyard.

One day, I showed them Joseph O. Legaspi’s poem “Ode to My Mother’s Hair,” a poem full of great nouns: cuttlefish, silt, crown of smoke, follicle, colostrum. I asked them, then, to write an ode to an object they associated with a person they loved. I was thinking, of course, of Legaspi’s poem, but I was also thinking in clichés: a grandfather’s watch, a mother’s dress, “The Gift of the Magi.” Keats’s urn, Stevens’s pineapple, Neruda’s artichoke. I wanted my students to tell me that the people they loved had objects that represented them, transported them, like Legaspi’s mother’s hair “which is always the other half of the world.”

They had trouble. I was used to the gap between the language that hooked them – age twelve is when we first hear the pop songs whose words we will never forget – and the language I showed them, but this was different: they were struggling for subject matter. Some thought of their baby sisters and brothers, still never without pacifiers or stuffed animals, but they did not picture the adults in their lives with significant objects. I looked around the room as they erased, wrote, and erased. I gaped at the generation between us, the gulf between native and naturalized citizens of an increasingly virtual world. When I was twelve, I carried around elaborately folded notes from my friends, cootie catchers with stupid destinies scribbled on them, handfuls of pop tabs. After my grandparents died, our house was strewn with objects that seemed to have been transported out of the time capsules that were their apartments: a navy woolen cape, a boyhood coin collection, a transistor radio in its own leather case.

Maybe, having been practically born on the Internet, my students simply had no objects. But this wasn’t true: they worried the lanyards that hung around their necks, clicked glittery pens, talked blushingly about the stuffed animals they still slept with. And they coveted anything consumable and shareable, just as I had at the same age: gum, or the little mints that made water taste like artificial apple, or Rollos. These were currencies worth more than actual money. One day in class, a fifth-grade student included me in her distribution of the gold-wrapped caramels, and I understood this as highest praise.

Maybe the problem was that they were rich. Things, I thought, for these children of polished people, were just what one had, not anything that became an extension of the body. The most attached they had seen their mothers be to an object might have been to their phones – everything else was disposable. Though volume, as anyone knows who has watched an episode of Hoarders, isn’t necessarily inversely related to attachment.

A few weeks ago, my apartment was burgled, and I thought again of my students wracking their brains for something to write an ode to. Our laptops disappeared, their absence immediately apparent from the laptop-shaped gap in the clutter on our desks. It took us hours to realize the few other things that were missing: a small wooden jewel box containing rings my mother had bought at flea markets as a young woman, a backpack with holes in the bottom. (One of the rings fell through the hole and found its way back to me.)

In the days that followed, I thought about the way my possessions clothed me. I have always been a messy person. Like some of my friends, I had tried to follow the advice of the Japanese organizing guru Marie Kondo, folding my clothes just so – but weeks later I was back to clutter. In truth, I am comforted by the array of stuff around me: on my desk, a program from a friend’s play, stapler, broken phone charger, Dr. Seuss coaster, paperweight made of the metal applique from a bookend, rock found on a stony beach in Scotland. These were handholds, or eyeholds, on the path backward through memory or forward through the unknown, just as Legaspi’s wonderful nouns were. I had been the kind of child who, when asked to write a story, drew pictures first.

“In a field / I am the absence / of field. / This is / always the case. / Wherever I am / I am what is missing,” wrote Mark Strand. When I first read that poem in college, I taped it to my door and thought constantly of the air zipping itself closed behind me as I moved, right up to the skin of my back. I wasn’t so attached to my objects – after a pang at losing certain talismans of my mother’s youth, I soon forgot the rings and the box – as much as I relied on them to describe me, in the mathematical rather than verbal sense: to mark the shape of me.

I wondered, two years after the fact, if I had made a mistake in building my students’ assignment from Legaspi’s poem, or in the way I talked about the relationship between the subject of an ode and its owner. Is the mother Legaspi describes really attached to her hair? While for the poet the hair carries safety, story, and identity, the mother is unsentimental: she cuts it off after a pregnancy, as many women do. The poet buries it in the backyard “dusting the plot / with sugar and cocoa, / moistening the mound with honey– / all the goodness from the world of the living. / I believed/ the earth resurrects / what is nourished in its belly.” For her son, the mother’s hair is his shape-maker: it makes the shape of a house, and the smells of home, and the story of their family’s survival, and memory. To lose such an object is a prelude to losing all of the things of which it is a component part, including his mother.

We misread people’s attachments to objects – we think they are about ownership and monetary value, about daily need and use. We think our grandparents carried their silver spoons or their best carpets or feather pillows or cast iron pans on their backs to this country because they were expensive, rather than because they drew the first little line in the shape of a home. In the only episode of Hoarders I have seen, I was appalled at even the psychologists’ and organizing specialists’ tin-eared dismissal of their subjects’ relationship to their stuff. They shame the collectors like bad animals, pressuring them with the imminent threat of the health department, rather than trying to help them figure out where their homes are underneath the accumulation of stuff, and of what stuff, in fact, that home really consists.

For my young students that summer, camp was perhaps the only place they’d ever been away from home. For some, home was very far away, in China or Norway. They were just realizing, in their adolescent ways, that the objects they’d brought with them for comfort did not begin to approximate the homes they knew: I just want to sleep in my own bed in my own room was a frequent refrain. But most of them had not lost their homes in ways either banal or dramatic, or any of the people those homes contained, so the failure of their objects to mimic home did not amount to a tragedy, or even much of a sadness. They might have to wait to write their odes until, in Legaspi’s words, their comfort, “besieged by wind and water, / teetered and threatened to split open, / exposing the diorama / of [their] barely protected lives.”

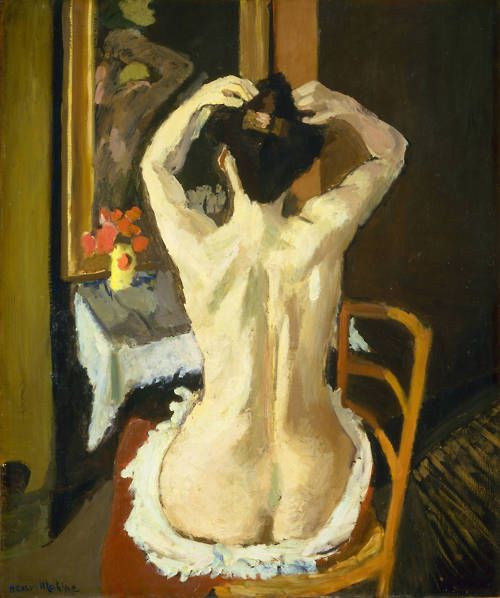

Image: Henri Matisse, “La Coiffure” (1901)