Some June afternoon in 2013, I was at a seminar for young writers, sitting on the director’s couch as he read through a poem I’d brought him. “You’re our resident miniaturist,” he informed me. He then added, “You might want to check out Cynthia Cruz.” A half-hour later, I was googling Cruz from my dorm room when I found a Rumpus interview published the previous year. I read not even a poem, but an excerpt from a poem, and immediately wanted to cry:

Woke on the highway,

Thin in my dead brother’s clothes.

I was gone but still dreaming.

A desert city strobing in the distance like sex.

(“Through The Night, Softly”).

Like the interviewer, “I read and fell instantly in love.” I didn’t even finish reading the poem until I checked Cruz’s two books out of the library some weeks later: Ruin (Alice James, 2006), from which the poem came, and The Glimmering Room (Four Way Books, 2012).  It didn’t matter, though; by that time, the words had already begun a mantra-like loop through my head. I was gone but still dreaming / A desert city strobing in the distance like sex. In just two lines, Cruz had articulated a magical tension between vast interiority and a literally flickering outside world. I felt this lurking all around me; now I had a way to say it.

It didn’t matter, though; by that time, the words had already begun a mantra-like loop through my head. I was gone but still dreaming / A desert city strobing in the distance like sex. In just two lines, Cruz had articulated a magical tension between vast interiority and a literally flickering outside world. I felt this lurking all around me; now I had a way to say it.

These two books, but especially The Glimmering Room, became quickly important to me. Cruz’s poems transfixed me in how they occupied a delicate space not between but encompassing opposites: beauty and squalor, trauma and heaven, reality and hallucinated dream. It was this attempt to reconcile inner and outer, high and low which I felt special kinship to beyond the surface content of the poems; they could have been “about” anything and I wouldn’t have felt less moved. Nevertheless, these books are masterful in their depiction of a distinctly American landscape of juvenile grunge, drugs, sex, mental illness, and the ruination of once pure childhood.

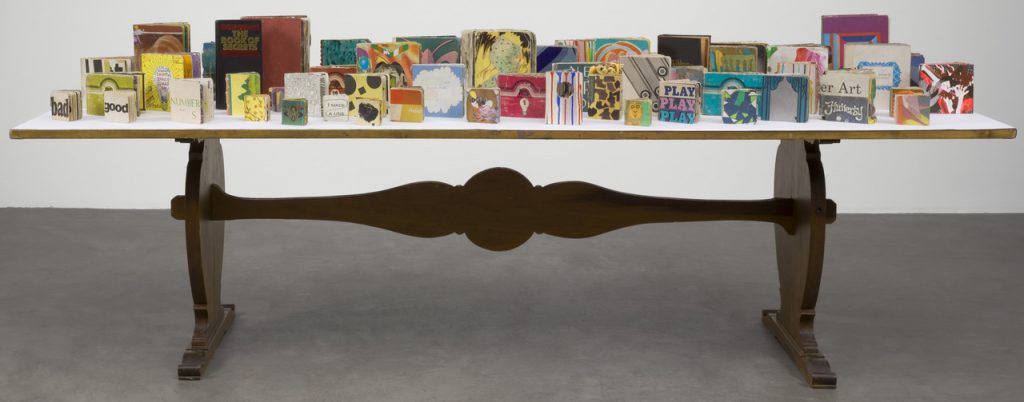

I’ve been awaiting Cruz’s third collection Wunderkammer (Four Way Books, 2014) since this time. “Wunderkammer” translates from German as “cabinet of curiosities,” which is an apt title for the collection given that what struck me most immediately about it was its lavish density. While Cruz’s previous books were textured by a landscape of 90s California grunge, Wunderkammer has a fur-and-velvet Old World lushness punctuated by Warhol Factory theatrical glam. We get an onslaught of shiny and exotic details: Dresden porcelain, rooms of strudel, Balenciaga and Chanel, Candy Darling, paste jewels, cream paste makeup, Germany and Berlin.

It’s clear that we are still in the other books’ same feverish world of “warm doom and contagion,” but amplified now is its excess and consumption rather than its waste and decay. Whereas Ruin and The Glimmering Room were marked by a sparsity that enacted a sense of divine, empty floating, the images in Wunderkammer are crammed closely together, their darkness derived from abundance rather than lack. The book begins:

Subverted my psychosis to watery ornament.

Was found drowned in a cream velvet

Mini gown, mind blown out like a city

With no electricity, all lines cut.

The brain, a kaleidoscopic disco.

But nothing another viewing of Mother

Courage couldn’t fix. And a trunk labeled

Trauma packed with piles of miniature Steiff.

I was dreaming evacuation.

(“Nebenwelt”)

Just as I found myself overwhelmed by Wunderkammer’s material sumptuousness, so too are the speakers of many of these poems. Inundated by ornament to the point of being “blown out”—a state that at once indicates apex and nadir, existence and non-existence—the speaker fantasizes about disappearing. Later in the poem, the details of this dream: “Lacing up my skating boots, I / Vanish, silvery paste of vapor on the ice / A row of pretty blonde dummies in the Dutch death / Museum.” This is perhaps the most surreal moment in the entire collection, but its position on the first page sends a message: the physical world is a place where it’s deadly to live in a female shell.

The perils of femininity have always appeared in Cruz’s work. I am reminded of the poem “California” from The Glimmering Room, one of many that describe the saving powers of androgyny: “My friend Billy dressed as a boy. / She cut her long blonde hair off / So that her father would stop / Always touching her.” Wunderkammer continues this equation of the female body and danger: in this first “Nebenwelt” (one of five poems with this title), the speaker is drowned by her velvet gown, becoming “death dressed in Chanel and Maharaja / Paste jewels, a vibrant green bacteria of sea and decay.” No matter how much she dreams of going vacant, the consequences of her sex will bring her back to Earth whether she wants to return or not.

“Nebenwelt” is a word coined by Paul Celan that, to quote Anthony Stephens, “denote[s] a level of experience besides that posited as ‘real,’ namely a world of metaphorical transformation, specifically that of poetic language.” It’s a title that speaks to the desire for and impossibility of mental escape that is a theme in Cruz’s work. Memory figures into Wunderkammer heavily, cycling between tyrannical presence and complete absence. “They’ll hook the gloomed world / Back into me, its menageries / And zoos of wounds, its museums / Of memory, and trauma” (“Self Portrait in Fox Furs, With Magic”). Memory becomes its own institution, towering and labyrinthine, always inevitably returned to.

The notion of collecting and indexing that is evoked through menageries, zoos, and museums (as well as via the book’s title itself) is important to Wunderkammer. Many of Cruz’s poems use physical places of containment as stand-ins for mental containment; her work is populated by a high number of rooms and institutions. Instead, however, of psych wards and child slums, Wunderkammer is dotted by hotels, chateaus, mausoleums.

In the bruise-like blue of the Gloomarium

You sit, nude, at your Bosendorfer

In a Dorotheum of music.

Hides and furs and black tattoos.

Guttural, your ruined, and unfathomable,

Fugue.

(“Slow Drug”)

The idea of a “gloomarium”—which, as far as I can tell, is a word of Cruz’s invention that should mean “a place that houses gloom”—could not be more perfect to describe Wunderkammer. It evokes a sens e of darkness as something to be collected, archived, catalogued. Each poem is itself a little wunderkammer, a strange miniature, of this inevitable doom. In a 2013 essay, which also appeared on The Rumpus, Cruz said, “Writing poems allows me mastery over a miniature universe. For those moments or hours, I am God of my kingdom.… My life is a box, tamped down.… I utilize this same structure, this same control, in my poems.” This notion speaks not only to the structural characteristics of Cruz’s poems, but also to the countless enclosures that exist within them. “The cold black box / Of memory’s coffin.” (“Nebenwelt”).

e of darkness as something to be collected, archived, catalogued. Each poem is itself a little wunderkammer, a strange miniature, of this inevitable doom. In a 2013 essay, which also appeared on The Rumpus, Cruz said, “Writing poems allows me mastery over a miniature universe. For those moments or hours, I am God of my kingdom.… My life is a box, tamped down.… I utilize this same structure, this same control, in my poems.” This notion speaks not only to the structural characteristics of Cruz’s poems, but also to the countless enclosures that exist within them. “The cold black box / Of memory’s coffin.” (“Nebenwelt”).

I find Cruz’s poetry spellbinding because it permits darkness to exist with nuance, to be both debilitating and sacred. This darkness—which seems to be inescapable given the colossal interiority of these poems—permeates everything, and yet is not shown to be necessarily sinister. Nor does Cruz glorify depression, drug abuse, anorexia, or any of the other conditions that give rise to the half-submerged consciousness that marks so much of her work. Wunderkammer teems with this duality: “sweet narcosis,” “poisonous heaven,” “warm current of death,” “botched Eden.” To me, the beauty that pervades these poems actually lends them an odd undercurrent of hope:

I waited in a sweet delirium of miracles

To be found out.

And at times, I swear, I could see directly

Into the thing I was

(“Self Portrait With Three Magi”)

To be found out for the thing you are underneath life’s decoration is powerful stuff. A couple years ago, I went through a long period where I wanted nothing more than to be literally invisible. This was not out of depression or shyness; it’s hard to explain other than that the muchness of other people’s attentions caused me to turn further inwards. Inwards was a place I also took to thinking of as a warm, dark room; a controllable box where the pronouncements of others didn’t matter. To have discovered during this time a line like, “I was gone but still dreaming,” allowed me optimism in the face of my own deep absence. It allowed me to feel I was being correctly seen. To sink below the surface can be lonely and mystical. To touch down in the dark sometimes just is—

Elysian,

Wandering the dark fields,

Its cathedrals of speech, and its shut

Doors. Until the world was a room

Of silver mollusks and eels, old black and white

Photographs, and obsolete maps strung on the walls.

I lost my voice. Then the delicate

Metal clasp came undone.

(“Nebenwelt”)