Call him Ishmael. That much is sure. But who Ishmael is—or more specifically, how we experience him—is, at this point, largely a function of how he arrives to us.

Moby-Dick, like so many other important books, is now in the public domain, free of copyright, and thus able to be reprinted in editions and forms as varied as an editor’s or publisher’s imagination. Hundreds, if not thousands, have taken up this task, creating quick-copied digital versions, hand-wrought artist editions, weighty hardcovers, cheap paperbacks, graphic novels—even a pop-up book.

This phrase, public domain, connotes both a legal status and much more than that. It means, most literally, that the text now exists in the public realm; ownership has been dispersed among all of us, with all the implications that travel with that. Moby-Dick does not belong to Melville—not anymore. Like any popular or important book, the idea of Moby Dick has long resided at least partially in the public consciousness. But when the text itself is owned by all of us, it becomes as malleable as its wide readership.

A recent tour of Moby-Dick editions, many of them from the Rare Books collection at my university library, revealed to me just how varied the textual experience of such a book can be. In the space of a morning, with a book cart in front of you, it is possible to encounter many Ishmaels.

Enter through the celebrated three-volume 1930 Lakeside Press edition, for example (credited by many for helping to jump-start Moby-Dick’s 20th century popularity), and you encounter first the stately Rockwell Kent illustrations, with their precise, art deco curves. Then you meet, well, not Ishmael, not yet. Instead, like some, but hardly all of the editions of Moby-Dick, this edition begins with an odd assortment of front matter. The first, Etymology, celebrates The Whale with definitions and translations in an eccentric series of languages. Reading this edition of Moby-Dick, one feels that the true subject is not a whale but The Whale, as much in concept as a particular animal, and thus a worthy object of Ahab’s pursuit.

The 1924 Everyman’s Library edition is another experience entirely. The simple book jacket tells us that, “The true university in these days…is a collection of books.” The 1920’s strain of humble self-improvement runs throughout the volume. This edition dispenses with that bothersome front matter and sits us right down with Ishmael—an Everyman himself, of course—who invites us to call him by his first name and travel the seas with him under the yoke of his terrible boss. A difficult journey for sure, but as the book jacket later tells us, this modest edition has cost us very little, and it’s not much to pay to be “intellectually rich for life.”

Read a well-worn edition from the university library’s main stacks, on the other hand—say, the 1967 Norton Critical Edition—and you travel with Ishmael through the eyes of a student with an active pencil and an honest streak. The front matter has been restored, as befits a scholarly edition, but based on the lack of notation our student did not bother to read it. Same for the chapters titled Cetology, The Chart, The Affadavit, The Blanket, The Funeral (why not?), Jonah Historically Regarded (okay, fine), Measurement of the Whale’s Skeleton, and about 40 more of the 135 chapters—nearly one-third of Ishmael’s tale, according to the table of contents and a pencil, marked simply OMITTED.

Which is not to say that our student did not engage with the text. Her underlines and commentary give us yet another version of the text, an Ishmael who leaps up from the sea of words and occasionally grabs her attention. What was happening in her young life, one wonders, that she both underlined and starred the observation that “meditation and water are wedded for ever”? And we should appreciate the bottom-line wisdom of a young person who reads “I am tormented with an everlasting itch for things remote. I love to sail forbidden seas, and land on barbarous coasts,” and declares, in blue pen, ISHMAEL SEES HORRORS.

Then there are editions in which the text seems, well, not beside the point, but pehaps just complementary to the point. The 1979 Arion Press edition, perhaps the most well-regarded fine press edition, feels as large and as heavy as a longboat; it is, in the words of James D. Hart, then-director of the Bancroft Library, “the most majestic presentation of America’s most monumental novel.” (Take that, Everyman’s Library!) Each page is an act of invention rivaling the novel itself—the font created just for this edition; the hand-made paper that evokes, ever so faintly, the color of the open ocean; the watermark, a white whale, that follows us across the pages. It is beautiful, and terrifying, in its way. Ahab’s obsession has met its printed match; the book has swallowed the sea.

And there are artist versions that are more whimsical in their intent, if no less lovely. How else to describe Sam Ita’s 2007 pop-up version, with its bright colors and impossible paper architecture? Like all pop-up books, it extends and distends the text, with whaling ships that burst out of its center, strings that raise paper sails, and most notably (to me, anyway), a giant paper hand that opens to unfold a giant paper Yojo—no longer the ironic tiny black idol of Melville’s book, but a god the size of Queequeg’s imagination.

And there are artist versions that are more whimsical in their intent, if no less lovely. How else to describe Sam Ita’s 2007 pop-up version, with its bright colors and impossible paper architecture? Like all pop-up books, it extends and distends the text, with whaling ships that burst out of its center, strings that raise paper sails, and most notably (to me, anyway), a giant paper hand that opens to unfold a giant paper Yojo—no longer the ironic tiny black idol of Melville’s book, but a god the size of Queequeg’s imagination.

Edmund Blunden asks:

Come tell me: of these two books lying here,

Which moves the heart and mind to tenderness?

When so many editions of the same book sit in front of you, how difficult, how lovely that question becomes.

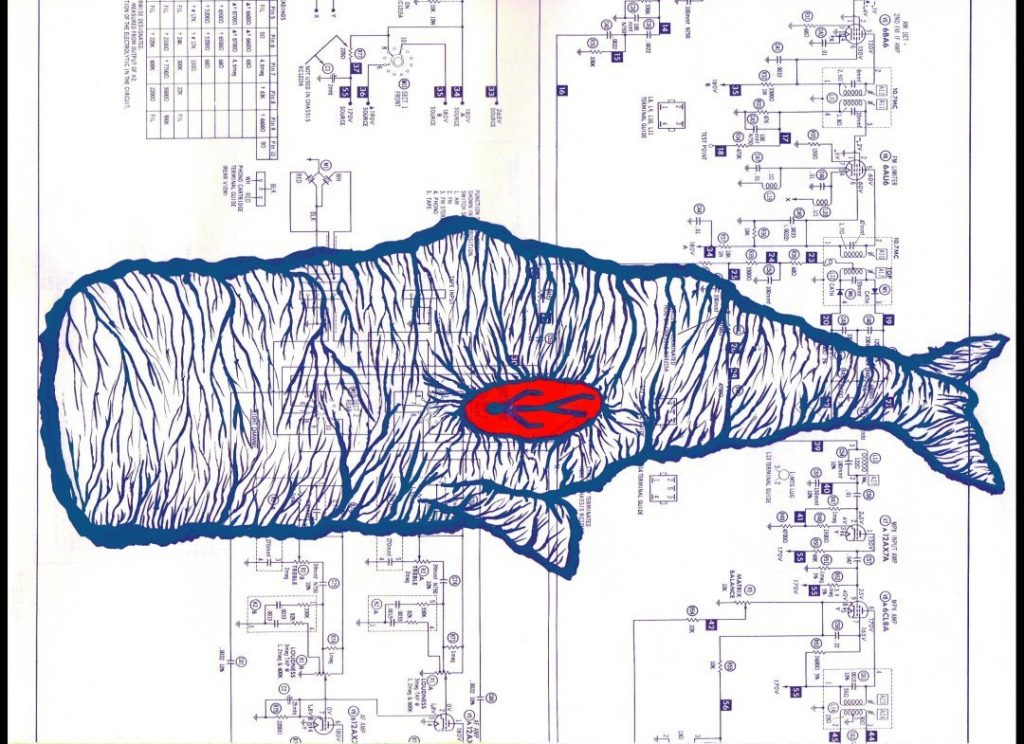

* Thanks to my colleagues Miriam Intrator and Nicole Reynolds for their contributions to this essay. Top illustration from Matt Kish’s Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page (Tin House, 2011), based on the Signet Classics edition of Moby-Dick.