A couple of years ago, I made the decision to apply to MFA programs in creative writing. Compared to medical school or law school, the application process for an MFA can sometimes feel like a crapshoot, with the odds of getting into a fully-funded program hovering somewhere below four or five percent (and some programs like Iowa, Michigan, Michener—gulp—even less!). Still, it seems that every year, a few applicants manage to get admitted to a handful of programs, which brings up the question of whether the process is as random as one might initially think.

As a caveat, I’ve never served as a reader for any programs’ admissions committee (for a genuine insider look, follow Elizabeth McCracken’s twitter and listen to everything she says!), but I happen to have been lucky enough to get accepted to several fully funded schools on my first try. Whenever someone asks me for advice, I get a little queasy, because I barely knew what I was doing back then. However, I’d like to think that I’ve had some time to reflect on the process and have spoken to many people, including students who’ve been accepted and faculty members. I’ve since graduated from my MFA and hold (at the time of writing) a Zell postgraduate fellowship in fiction at the University of Michigan.

I’ll skip the general consensus—polish the writing sample, apply to more than one school, get feedback on your materials, etc. Instead, I’ll offer some less common ones that I thought worked for me. I hope they help with your application, and I’m certainly indebted to many writers who came before me and similarly shed light on their own experiences.

- Presenting yourself. Most of us writers tend to dislike being pigeonholed, or to accept the idea that there are certain themes or styles we keep reverting to again and again. I definitely struggled with this (and continue to) but for the application process, presenting ourselves in a way that is unified and meaningful can sometimes spell the difference between sticking out in the pile or not. I write a lot about the Philippines, where I grew up, and this location not only influences the setting of my stories, but also informs my thematic sensibility as well as my identity. My personal statement talked about my background growing up in a predominantly Christian and Chinese-Filipino family, the conflicts at the dinner table as a result of our ethnic and religious upbringing, and how these issues are explored in my work. My fiction samples were chosen with this in mind (of course, they also happened to be my best work at the time), and I imagine my recommendation letters further attested to my experience as an immigrant. As a result, I believe I demonstrated myself as someone who deeply cares about what I write and has something important to say about the world around me. A place or region might not be the element that binds your application materials together. It might be a style, philosophy, or occupation—but whatever it is, it should resonate meaningfully in all aspects of your work (you can even ask your recommenders to talk about it). If readers can come away with the feeling that they know you and what motivates you to write, then you only need to show that you also can write.

- Range and length of sample. This might sound like a contradiction to the above, but it really isn’t. Rather, this is the part where you get a chance to display your skill and flexibility as a writer. For my sample, I chose three stories with varying styles: fabulist, comedic, and straight realist. They also differed in their lengths: short, medium, and long. What kept them all together was the setting of the Philippines, which again referred back to my personal statement and kept them from feeling haphazardly chosen. You might wonder if this is a good idea, since schools often just ask for 25 to 30 pages of creative sample, and might even say something to the effect that they’re looking for “a demonstration of sustained, quality work.” I debated with myself on the correct approach, and you might not agree with my conclusions: If programs clearly ask for just a single story, and if they feel more traditional in their aesthetics, then perhaps sending a longer story is better. However, the risk of sending one story is the risk of increasing subjectivity, and has to do more with the practical reality of the selection process than anything else. We all know that readers have different tastes, and if for some reason they don’t connect with the first few pages of your work, they most likely won’t read on. If you present them with a shorter work first, they might be willing to read the beginning of the second story, and if they still don’t like that, then the third. If each story is different stylistically, you’re increasing the chances that one of these would be appealing to the readers, and they might reconsider the stories that they passed on the first read.

- Potential. I’ve heard anecdotes of applicants being turned down because the admission committee thought they were “overqualified” to be studying in an MFA program. This probably doesn’t apply to most of us, but the principle remains: administrators are looking for people they believe can get something out of the two-to-three-year experience. In other words, they’re looking for writers’ potential as much as writers’ ability. I can certainly speak to this. When I applied, I’d barely taken any creative writing workshops. I’d just started writing literary fiction and I was unpublished. I took screenwriting as an undergrad (a related field, I know) but I still emphasized the things I anticipated learning from an MFA, including the benefit of being in a community. I did not downplay my background in screenwriting (and as it happened, also journalism), but I was able to articulate how each tradition influenced me as a writer. You might be someone who’s majored in creative writing as an undergrad and knew for a long time that you want to write literary fiction. That’s okay (in fact I think that’s great!). But you still have to find a way to communicate your limitations while playing to your strengths. To a large extent, it seems to me more of an attitude check: nobody wants to be with the writer who feels privileged and entitled to a seat at the MFA table.

- Preparedness. Sometimes, perhaps because I got in on my first try, I wonder if my acceptance was a fluke, and if I was really ready for the MFA experience. Of course, I’ve heard many people who felt similarly, some who even have a lot of creative writing background under their belt. The impostor syndrome aside, I do think that it’s good to gain as much exposure to the literary world as possible before applying to an MFA program. This not only gives you a better sense of why you write and what you write (going back to my first point), but moreover it increases the likelihood that once you are accepted, you’ll know how to make the most out of your time and the resources being offered. I had a wonderful experience at the University of Michigan—indeed, I’ve never read or written more in my life than I did at that point, and I could not have asked for a better set of cohort or mentors. I have grown exponentially as a writer. Rightly or wrongly, though, I did consciously set myself apart as someone who was a beginner, who had the most to learn about writing literary fiction. This attitude has enabled me to develop in leaps and bounds. At the same time, I could see how—had I been further along in my progress—I could’ve used the MFA in a different way: writing that novel I’ve always wanted, giving more thought to the direction of my career, the business side of the industry, finding an agent, etc. I think there’s something valiant and admirable about finding yourself as a result of experimenting during the MFA years, but it might also be worth considering and being aware of the different trajectories in entering a program. As a suggestion for preparing yourself pre-MFA-application, I highly suggest going to a conference (the Napa Writers’ Conference, Wesleyan Writers Conference, and the Key West Literary Seminar being some of the more well-known ones I’ve personally attended and recommend).

- On success. My final note on the application process is less of a tip and more of a reminder. When the time comes around to February or March, and should you find yourself not getting into the programs of your choice, recuperate from the rejections and take them in stride. View the result both as a sobering reminder of the odds stacked up against anyone applying for an MFA, and also as an opportunity to become better prepared, so that if you do get in later, you will be in an improved position. Similarly, should you be fortunate enough to get into your top programs, view the achievement as the means to an end, and not the end in itself. If a study were to be conducted on MFA admittances, I’m almost sure that the findings would show that acceptances to programs are in no way predictive of future success in publishing. Only diligence and perseverance are positive indicators of writerly success, and in this sense, we all can take comfort in the fact that all of us have a fair shot if we’re in it for the long haul.

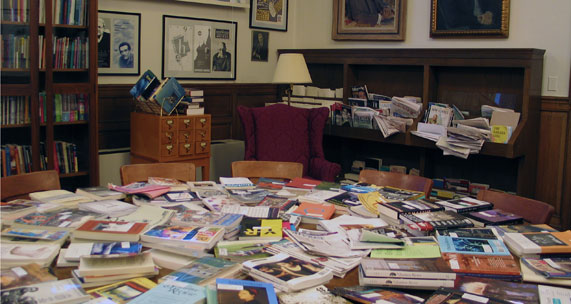

Image: The Hopwood Room, where some workshops are held at the Helen Zell Writers’ Program, University of Michigan.