To me, Solmaz Sharif’s poem “Vulnerability Study” is perfect:

I love how each stanza in the poem promises—but stops just short of—climax or oblivion.

I love how the last image undoes the image that precedes it: pins slipped in, nails pulled out. What this poem gives, its snatches back: first, the heft of bodies—“your face turning from mine / to keep from cumming”—replaced by, at the end of the poem, the body’s conspicuous absence—“a wall cleared of nails / for the ghosts to walk through.”

I read this poem for the first time recently, just a few days before I travelled with Eric, my boyfriend of three years, to visit my grandmother in Southern California.

“Bring him to California,” she said to me coyly one night last spring, her highball sloshing as she reached for a hug, “before it’s too late.”

Everyone always laughs when she makes these pronouncements: “Take the book. I probably won’t have time to read it.” “If Hillary Clinton becomes president, I hope I’m dead.” My grandmother, in these moments, is wry and provocative, so I laugh, too, but her statements also stir in me a feeling akin to that evoked by Sharif’s poem—something like the surge of empathetic shame and pain you feel when a dancer falls onstage. This is the feeling of watching someone else unwittingly perform their own vulnerability, a feeling Sharif manages, via beauty and understatement and calm, to both soften and crystalize, to both ease and magnify.

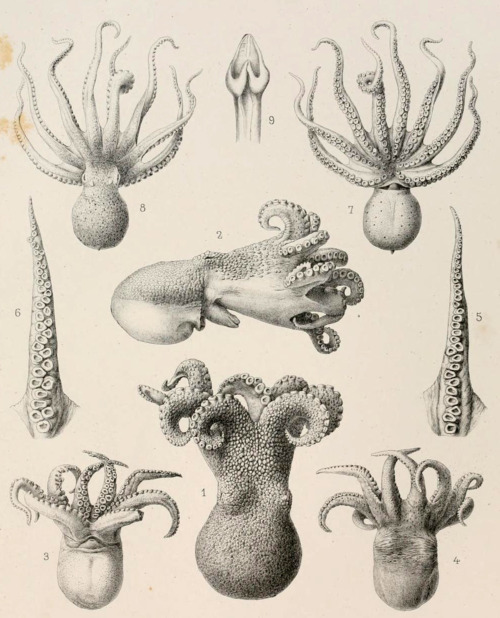

So I brought Eric to my grandmother’s house, where my father was born and where his father recently died. Her house faces a deep green canal, and every summer as a child, I swam and fished here. My sisters, my grandfather, and I would prop our poles on the sea wall, return to the house, and monitor our lines through the dining room windows. The creatures we hauled up from the bottom of the canal were near-mythical to me: miniature sharks, fish with hard pronged fins, rays, an octopus. When we caught the octopus, my grandfather lifted it into a net and pried the hook from its beak with pliers. Then he peeled its arms from his and tossed it off the dock, back into the water. As a tween, I stopped fishing in the canal and instead self-righteously protested the unnecessary cruelty of catch-and-release and live bait.

The word vulnerable comes from the Latin vulnerare, to wound. By now, I’ve read Sharif’s poem dozens of times, clinging, like the octopus wound around my grandfather’s wrist, to the hand that hurt me. That is, the poet’s hand. Other people’s vulnerability discomfits and distresses us, but that’s what Sharif gives us in each of her film still-like stanzas—in this way, her poem wounds us.

Or at least it remind us of our wounds, presses a thumb to the bruises we already have, provokes us to recall our most vulnerable moments and add them to its catalogue. “Vulnerability Study” is a list that wants expansion. So, perhaps, what I find perfect about this poem is that it resists perfection. Perfection in the classical sense of the word—the Latin perfectus meaning fully realized, complete, finished.

The night before Eric and I flew back home, we sat outside drinking brandy with my grandmother and parents, our feet propped up on the sea wall, talking about my grandfather’s decision to build their house here, on the water. When Eric and I stood up to turn in the for the night, my grandmother grabbed Eric and said, “I thought I’d never meet you. I thought you were a vapor.”

Vapor. Water in the process of turning into air. In a way, my grandmother was right about Eric. We’re all in the process of disappearing, thus vulnerable. First, the heft of bodies, then the body’s conspicuous absence.