I discovered British sculptor, David Nash’s work as perhaps the artist would appreciate—while wading through a meadow of Queen Anne’s lace, salvia, and Rudbeckia. Along the quiet walkways at the Frederik Meijer Gardens, the Sculpture Park offers an impressive collection from well-known artists such as Rodin, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Claes Oldenberg, Louise Bourgeois, Kiki Smith, Roxy Paine, and many others. Off the walkway, weaving art and nature, a meandering meadow took me to an opening, valley-ed between a screen of deciduous trees. Here I found Nash’s, “Dome”, an intriguing clumping circle of 46 cast iron mounds that neatly brought to mind the spirited growth of fungi after a good rain. In the distance “Scarlatti” by Mark di Suvero teetered hulkingly, but there was something transfixing about Nash’s “Dome” that promised more to come.

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”, is an exhibition that embraces the integration of horticulture and sculpture, featuring more than 25 works indoor and outdoor. Any visitor is able to discover and question the works placed with whimsy among the palm trees and ferns of the Lena Meijer Tropical Conservatory, such as “Red Throne” and “Three Iron Humps”. They could be found charismatically situated between cacti and succulents of the Arid Garden where I discovered “Apple Ladder”. However, it was inside the white walls of the Meijer gallery—well out of Mother Nature’s reach, where I really experienced David Nash’s work. Inside, the hushed gallery space offered an immediate spiritual clarity like a church. It was here, and not in the direct landscape that I understood Nash’s collaborative spirit with nature.

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”

Nash is an obvious sentient being. His childhood was spent in Wales, working with his father, clearing the fields, and replanting trees on family land. This offered valuable time discovering the properties of wood, which lead to a life-long interest. Nature provides a material for Nash, and a chance form. His language is wood—oak, elm, ash, lime, yew, redwood and mizunara. He speaks it very well. The life-force of the tree and it’s inherent properties; light, moisture, minerals, and gasses, are thoughtfully considered while approaching every sculpture. He shapes and gouges, using deep cuts as linear drawing by way of chainsaw. They are not fastidious. However, the most important methodology in his work is…letting go.

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”

The limits and controls of his locally sourced wood keep Nash in a careful balance. Along with his authorial hand, his most enigmatic tool is the actual element of time. He prefers to work outside for practicality. He cuts away and shapes his work where the tree had fallen, right where the tree had grown. Being in the elemental forces of nature become part of each piece. But the timber is unseasoned and, therefore, full of moisture. And long after finishing, the wood continues to dry. During this natural process there is so much tectonic shifting in the rough-hewn surfaces that it commands the aesthetic structure of the work. Without intervention, Nash’s sculptures warp and twist. Instead of an artist controlling the work, he is letting the work go. The cracks and fissures are nature’s finish.

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”

“Crack and Warp”, is the perfect example. This tapered monolith exemplifies Nash’s meditation in form and composition taking cues from minimalism. Nash slices the long, flat sides in rough-cut horizontal lines. Up close the incisions are very expressive. A chainsaw would allow for this. Fast cuts gouge, slice off edges, and dissect the surface, digging and routing without fragility. Their spacing and depth are imperfect and vary slightly. In this case nature’s finish is an organic reaction to Nash’s geometric decisions. The result is a standing column that wavers and dances. Light passes through its wooden gills. The thinner the section, the more the materials warp. The more they crack, the more they brake off. Nash captures the vitality of living, the balance of nature, and the imperfection of human nature. It is exciting and unapologetic in its visual experience.

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”

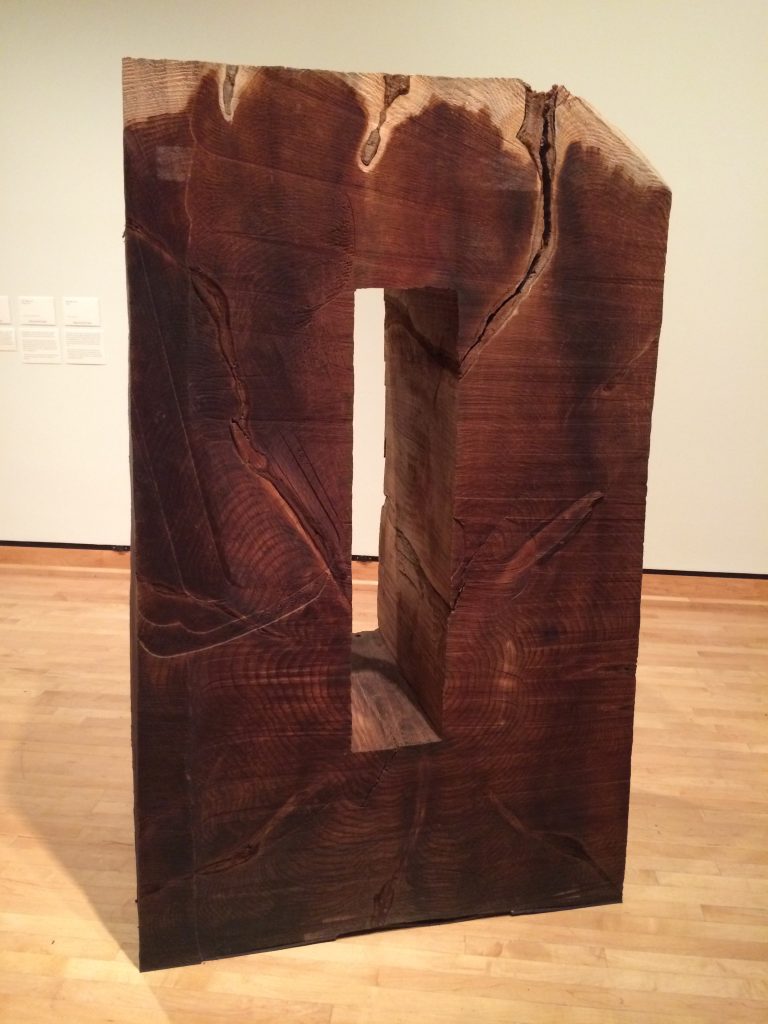

Some of Nash’s works closely resemble the natural forms of the trees themselves, like “Cave” and “Red Frame”. Honoring the spirit of the material, Nash leaves the actual textures of the wood and rooting structures for all to see. Here the artist is showing us time. Cracks and warp certainly stand for this, but it is also literally in the growth rings of the tree. All details are displayed in a tender light beneath their tough corpulent shapes. These works are not at all sentimental.

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”

My favorites recall ethnographic objects. His, “Vessel Series” are mysterious, haunting monuments. They can be seen here in an upright composition, showcasing Nash’s observational interest in the vertical growth of a tree. Perhaps they are a meditation on connecting the earth and sky. The series is also presented in the horizontal composition of “Two Vessels”. This pair of charred oak pieces affects me the most. Their long and low shapes are riveting, sluicing the gallery floor with a dark prowess. Their gesture takes me to the carved cedar canoes from the Salish tribes of the coastal northwest. Their dramatic profiles suggest these ominous shapes in the same way. And like many of Nash’s works, “Two Vessels,” has been charred, transforming the color and texture of wood to an intensely rich, carbon patina. Nash creates this blackening with a blowtorch. The blackening of the surfaces are not just a tone or a color, but a deeper dimension that appears bottomless. Burning the wood creates a surface that is honest, calling to mind the big subjects of life, love and death. The vessels appear to be cutting into an invisible surface, standing for the relationship between memory and the sensation of the passage of time.

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”

I think that Nash has a generosity of spirit in sculpting that makes us want to share those profound experiences with nature. He is deeply connected to the environmental movement, with an awareness to look after our natural resources. When I was living in the Pacific Northwest, I was contracted to make a documentary concerning the rebirth of a very important indigenous tradition: the carved cedar canoe, dugout of a single cedar tree. In “Tribal Journeys: the Resurgence of the Canoe Nations” I had the opportunity to interview Suquamish elder Ed Carriere. As he was working a canoe in his outdoor studio he candidly expressed to me something I never forgot. He said that the cedar canoe is more than just a utilitarian vessel. It is a deeply respected spiritual object that begins its long life as a tree in the forest and continues in the prayer ceremonies as it is felled and then crafted into a dugout canoe. But the vessel is also a metaphor for the importance of community, the process necessitating hard harmonious work. I understood it as a living, spiritual object.

Partly charred cypress and charcoal on canvas

“David Nash: From Kew Gardens to Meijer Gardens”

Spending time with Nash’s work confirms that he is entrusted to nature. The relationship between the hand of nature and the hand of the artist is deep and communal. He earns the respect of the material and we trust his perception of nature, ancestry and sense of place. Nash’s aesthetics are born out of indigenous materials. Their physical presence matters, their materiality matters. Earth, air, fire, water, he follows the elements that demand boundless change and a haunting spirit.