In his story “A Voice in the Night,” Steven Millhauser describes an aging author’s insomnia:

He’s always been a light sleeper, the slightest sound jostles him awake, but this is different: he falls asleep with a book on his chest, then wakes up for no damn reason and strains his neck to look at the green glow of his digital clock, where it’s always some soul-crushing time like 2:16 or 3:04 in the miserable morning. Hell time, abyss time, the hour of no return. He wonders whether he should turn on his bedside lamp, try to read a little, relax, but he knows the act of switching on the light will wake him up even more, and besides, there’s the problem of what to read when you wake up at two or three in the godforsaken morning. If he reads something that interests him he’ll excite his mind and ruin his chance for sleep, but if he reads something that bores him he’ll become impatient, restless, and incapable of sleep.

I know this problem—“the problem of what to read when you wake up at two or three in the godforsaken morning”—well.

As a child, I’d often grow restless at bedtime. I’d lie awake, diligently inflating each of my recent wrongdoings—flipping off other kids at school, lying about it—into sins that burdened and distressed me, relentless problems of my own making. I could neither calm myself nor sleep.

Enter: my mother. She’d trace my face with her fingertips, smooth my eyebrows, press my temples with her thumbs. She’d count with me, backwards from one hundred by threes.

Sometimes, with my sister and me, she’d construct a city of the imagination: a city built, by us, out of candy. We lived among the coastal hills of the northern Bay Area, so city meant San Francisco. Blue Jell-O bay. Red Vines bridge. A frenzy of aquamarine jelly sharks in the gelatin water. What strikes me now as too cute, too bright and too sweet, was then soothing and indulgent—an opulent, decadent fantasy that elbowed my fraught obsessions out of my head, out of the room.

Of late, I’m fretful before bed, yes, but I’ve also become—like Millhauser’s Author—a light sleeper, waking suddenly and absolutely when the cat traverses the bed or my phone sounds with an errant text message. Up and alert, I can’t relax.

So, how do I still my mind in the middle of the night when it damages, like a moth wing, at the slightest touch? How do I soothe myself when I react, as if allergic, to my own need for sleep? Just calm down, I plead. My insomnia strides forward, unchecked.

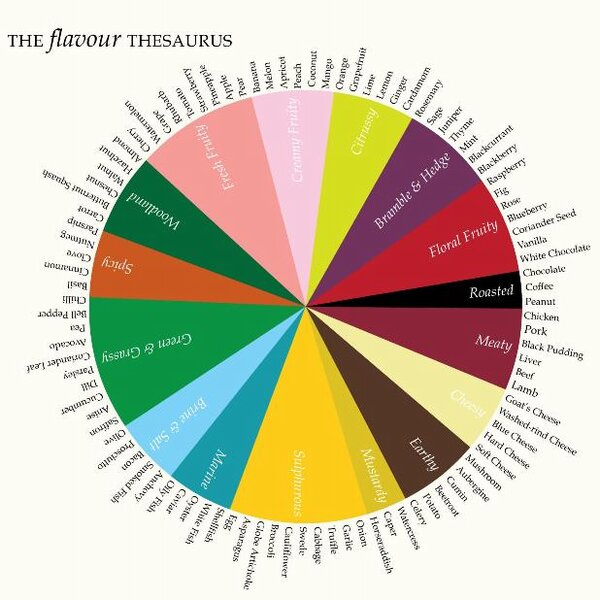

Enter: The Flavor Thesaurus by Niki Segnit. Though marketed as a flavor-pairing guide for the creative home cook, it has served me, recently, as a wee-hours map of Fantasyland. It hits that Millhauser sweet spot: plotless but not dull, tedious but sensual. See Segnit’s entry for “Blackberry & White Chocolate”:

Put a small bar of white chocolate in your pocket the next time you go blackberrying on a sunny, late-summer afternoon. When your bag has begun to leak crimson juice, find a warm spot and carefully unwrap the chocolate, which should have melted by then. Select a handful of your best berries, check them for bugs and dip them in the chocolate, safe in the knowledge that even if you were to eat the whole bag you could always pick some more.

And her entry for “Grapefruit & Avocado”:

This combination is a modern classic in a salad with lobster, plump shrimp or fresh crab. A café in Montpellier calls this salade fraîcheur and serves it with a shot glass of gazpacho on the side. On a witheringly hot afternoon, it was enough to rehydrate the body and the soul. The brightness of the flavors is one thing, but there’s also pleasure in feeling the soft butteriness of avocado against the grapefruit’s vesicles, tautly rippled like wet sand after the tide’s gone out.

We talk often of world-building in fiction, but what of the world Segnit constructs? It’s fanciful, lush and ritzy, out of reach and rich in detail, a place where, when my own room and my own bed fail me, I can finally forget to fall—and so then fall—asleep.