Last week I travelled to southern Mississippi for my grandmother’s funeral. I flew into Gulfport late, just before midnight, on Friday, July 4th, fireworks bursting mutely below the plane as it descended along the coast. Five days earlier, in a hospital in Atlanta, my mother’s mother had decided to cease the treatments that had been keeping her alive—alive but in pain, listless and bedridden—for months. Three days after her last treatment, she died, and when my mother and I spoke on the phone that day, we spoke mostly of the obituary I would write.

“What you don’t know, leave blank,” my mother said. “I’ll fill in names and places and dates later.”

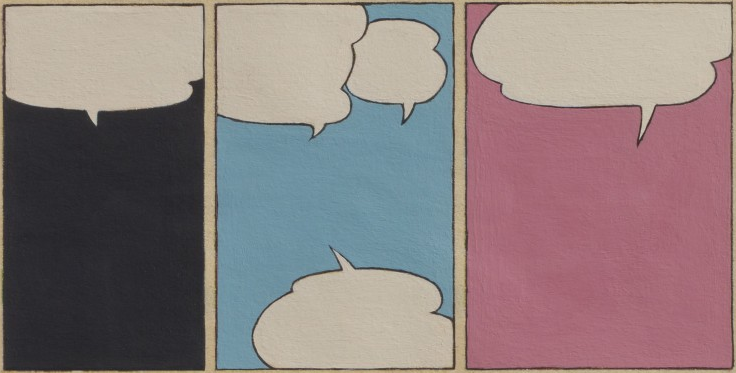

I had never written an obituary before and dismissed this fill-in-the-blank process as my mother suggested it. And yet, that night, sweating on the couch, my computer burning the tops of my thighs, box fans propped on the windowsills, I composed the obituary precisely this way, brackets fencing in each blank space: the name of the town where Granny was born (Two Rivers, Wisconsin), the year she born (1934), the names of her parents (Eloise and Arnold), how long she had known my grandfather before they were married (80 days), the name of the university she attended (Memphis State), the name of the university newspaper she edited (The Tiger Rag), etc. When I finished, I e-mailed my mother a draft gaping with white space.

I lifted the structure of the piece directly from another obituary, mimicking its language, its tone, how it opened, how it closed, what information was included and omitted. I feel ashamed now, guilty even, that I relied so completely on the strictures of the form to dictate what and how I wrote about my grandmother. After all, I could never—would never—write poetry this way. The kind of poetry I try to write, by its nature, rails against the limitations of its form, courting that necessary tension between convention and invention; the form doesn’t exist before the poem, nor the poem before its form.

But the obituary form is form par excellence. It’s formula—a formula that prefigures its content. Like air inside a balloon, the content of my grandmother’s life—names, dates, places, accomplishments—took the shape of its container.

On Tuesday morning, during my grandmother’s funeral mass, the priest noted how, though he’s presided over many funerals, each death feels like the first. I agree. This is the unwieldy paradox of loss: how utterly quotidian it is to lose someone, how we’re never prepared.

So when death abducts us—us, the living who remain—how can we know what to say? When we’re disoriented by loss, how can we navigate language? How can we find the right words, how can we place them in the right order? We can’t. We don’t have to. To write an obituary requires no such inconceivable deliberation, no such ambition. Pre-fab, fill-in-the-blank, obituaries don’t summarize lives lost, nor do they capture, really, the essence of the people they remember—how could they? They provide us—us, the bewildered and angry, the bereaved and grieving—with structure when our sadness is at its most unbearably nebulous, uncontainable and irrepressible as the wet heat of July under our clothes, on our skin.