These summer days, the world is nestled inside the sun. The long, bright afternoons give way to nights that barely conceal a glow. Light sometimes feels like an opening, but not always a welcome one. I suffer from headaches, light induced and light intensified, that usually begin behind my eyes. (Two doctors have used the word “migraine.” If they are right, I am lucky not to suffer from the most debilitating varieties.) Light can feel like a radiant cage, but over the years I have learned to encounter brightness when am I am able, shade my eyes when necessary, and rest out headaches if I can. I have learned to co-exist with light, and in the process, have started to question what it seems to mean.

John Berger (a person who wears many hats–art critic, novelist, painter, and political activist) describes the pain, both physical and symbolic, of (newly-restored) vision in his small book Cataract. The book records Berger’s impressions of his cataract surgeries.

After this operation, unlike the first, the treated eye began, an hour or two after the intervention, to hurt and this continued for about a day. With mild painkillers it was quite tolerable. The passage through this small pain was inseparable from my journey towards a newly visible world.

Nudged on by Berger’s narrative of “small pain,” I begin sifting through types of light, wondering if I will find a pattern. I start the work in my bedroom, which is darkened by thick blinds that block out the relentless glow of street lamps. Light still sneaks in under the corners of the shades, and when the curtains billow, slices of light flash across the floor. In the early afternoon, a parallelogram might hover beneath the ceiling. Most enigmatic of all are the circles projected onto the wall across from my bed. They burn with the unfinished urgency of light-as-metaphor.

Late in the afternoon the sun presides over my exposed porch. My initial report: I am squinting, and recall the old admonishment not to stare into the sun. I move into the shade of my living room, and there I “see” light’s utility in the objects it illuminates: a chair, a table. Berger describes “…the quality of firstness that light bestows. As though light and what is light arrive at the selfsame instant.” The sunlight is warm, and I feel as if it is inviting me somewhere expansive and safe. I question this invitation, intrigued but suspicious. The next afternoon, again through a window, I examine the light. Now it is cool and netlike. Today’s invitation is less seductive than yesterday’s. It is just as abstract but somehow more vague. I am beginning to feel lost in this work and annoyed with light, which I can never quite “see” because it is almost always there, continually reasserting itself as omniscient narrator of a seemingly plotless story about…itself? I return again to Berger, who writes:

I become more aware of the air, the space, between things, because that space is full of light like a tumbler can be full of water. With cataracts, wherever you are, you are in a certain sense indoors.

Berger reminds me that I am indoors, examining light through windows. I acknowledge my dependence on the build environment. In here a nascent headache feels manageable since I can immediately attend to it with familiar tools (Tylenol, drawn shades).

Artificial lighting runs the gamut, from the unrelenting glare of overhead lights to the melancholy pulse of attic lamps with fabric-wrapped shades. I find overhead lighting unnerving in its surveilling illumination. I prefer instead to fill rooms with a chorus of small lamps, each one adding its localized light. At night I sometimes use no light at all. Instead feel my way up stairs, around corners, and through familiar doors.

Indoors, examining lamps and peering through windows, I recall the James Turrell exhibition I saw last summer at the Guggenheim. I am starting to feel like I am crawling through a pinhole, so I am happy to remember my way out of the house. James Turrell is associated with the Light and Space movement, which the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, describes in this way: “As immaterial as Conceptual art, Light and Space art focuses less on ideas than on sensory perceptions.”

On his website, Turrell describes his work in this way:

I make spaces that apprehend light for our perception, and in some ways gather it, or seem to hold it…my work is more about your seeing than it is about my seeing, although it is a product of my seeing.

(For the curious, the website gives an overview of Turrell’s major works by date, type, and even “Cartographic Timeline.” 2013-14 was an especially busy year for Turrell exhibitions, as you can see here. Highlights include a retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the exhibition I saw at the Guggenheim.)

The word “apprehend” can mean several things: to perceive more generally (and possibly fearfully), but also to understand, and even arrest. Whatever he means, Turrell announces that he, and the spaces he makes, are intermediaries between light and everyone else. I wonder, too, what it means to call my seeing a “product” of James Turrell’s seeing, and further, I wonder of what, or whom, James Turrell’s seeing is a product.

I visited the Guggenheim exhibition on a “Pay What You Wish” Saturday. A long line of people had already twisted around the block when I arrived. The line moved quickly, and soon I was inside. The sounds of public looking filled the space. My partner wondered why everyone in the rotunda was gazing up (we did not know about the exhibition’s main installation when we arrived). We made our way up the building’s inclined ramps to its upper floors, carried along by the organism of the crowd. In the spaces containing Turrell’s early works, squares of light hung in the air, and people filed past. Because there were so many of us, someone occasionally stepped into a projection and was told to step back. Though I understand the impulse to “preserve” a uniform viewing experience for visitors, being policed in this way made me feel more uneasy than the unpredictable mass of people. Unlike the usual don’t touch museum protocol, here there was nothing that could be dirtied by a human hand—only light to obscure and a viewing experience to “ruin.” The Guggenheim describes the Turrell exhibition as “creating a dynamic perceptual experience of the materiality of light,” and suddenly this seemed overwhelmingly apt.

Wondering if others had experienced something similar at Turrell exhibitions, I found Maya Gurantz’s piece “James Turrell: A Dissent—Part Two: Four Thoughts on James Turrell, or Where is the Body?” She describes a similar experience at the Turrell retrospective at LACMA:

Despite the experiential and phenomenological nature of Turrell’s work, in his realm, the body is vestigial. Each piece maintains an ideal viewing position, usually seated. The viewer is meant to sit on the chair or bench—and look, and look, and look. The light installations with their layered, textural beauty become living, trembling color field paintings. The visual information vibrates between the eye and perceiving brain without ever once passing through the body. The body becomes the eye.

Not only is the body unnecessary, it is actively interruptive, destructive. A security guard cautioned me not to get my shadow on one of the works. The staging of disembodied visual pleasure falls apart the moment another viewer’s body enters the frame of vision or, God forbid, speaks. This in turn instills feelings of contempt within the viewer for the bodies and voices of fellow museum-goers: how dare these humans ruin my looking?

An art in which the artist demands (via museum personnel: see Gurantz’s discussion of the hierarchies of exhibition workers) a viewer not to “get [her] shadow” on it means she must carefully plan and monitor her movements, and never get too close to the light. Viewers cluster on the margins to gaze across the threshold. This relation of viewer-to-work differs from the one made possible by Kara Walker’s art. In projections using cut-paper silhouettes, Walker depicts scenes in which unsettling and unsettled narratives of race, gender, power, and violence play out. Viewers circling a gallery wind up entering her works as silhouettes, just like those created and projected by Walker. (For more information about Walker and her projections, see this discussion of her work at the Chicago Humanities Festival.) While we must stand back and receive Turrell’s light, there is no escape from Walker’s.

“Mistress Demanded a Swift and Dramatic Empathic Reaction Which We Obliged Her” (2000) by Kara Walker.

The bright light and pooling shadow of Turrell’s early works made my sensitive eyes throb, so I was glad to return to the lower rotunda for Aten Reign (named after the Egyptian sun-disk god Aten.)

View of Aten Reign (2013) inside the Guggenheim.

We found open seats after a few vigilant minutes. “In Aten Reign,” according to the Guggenheim, “daylight from the museum’s oculus streams down to light the deepest layer of a massive assembly suspended from the ceiling. Using a series of interlocking cones lined with LED fixtures, the installation surrounds this core of daylight with five elliptical rings of shifting, colored light that echo the banded pattern of the museum’s ramps.” There is a lot of equipment supporting Turrell’s vision (as is the case, to some extent, with every exhibition). We reclined and watched the lights’ colors shift. The color changes happened so slowly and imperceptibly that it was, as my partner observed, often difficult to tell when a change was happening. (This progression from one color to the next is not unlike the narrative of light’s shifting appearances throughout a day.) The entire space was awash in colored light. The Frank Lloyd Wright-designed building’s oculus was still visible, but neatly folded into Turrell’s “elliptical rings.” I was so absorbed in Turrell’s light-and-color-sequences that I forgot the building’s gazing “eye” (which also resembles, or allows in, a disk of sun and sky) was still there, both material and metaphor.

I am not sure what I have come to understand about light. At the Guggenheim light felt grandly enigmatic, perhaps because of its context and Turrell’s language. Both reinforce uncomfortable notions about who gets to be sagely arbiter of light’s presentation and elusive meaning(s). Alberto Rios opens his poem “A Physics of Sudden Light” (which I originally found along with images of Turrell’s art on a website I can no longer locate) with the line “This is just about light.” Indeed, I have “just” been examining light, a reliable, warming, overwhelming, vague, and sometimes troubling part of every day. My “confusion here” is, I hope, “one more part of clarity.” I am not where I was but I have not moved.

A PHYSICS OF SUDDEN LIGHT

This is just about light, how suddenly

One comes upon it sometimes and is surprised.In light, something is lifted.

That is the property of light,And in it one weighs less.

A broad and wide leap of lightEncountered suddenly, for a moment-

You are not where you wereBut you have not moved. It’s the moment

That startles you up out of dream,But the other way around: It’s the moment, instead,

That startles you into dream, makes youClose your eyes – that kind of light, the moment

For which, in our language, we have onlyThe word surprise, maybe a few others,

But not enough. The moment is regularAs with all things regular

At the closing of the twentieth century:A knowledge that electricity exists

Somewhere inside the walls;That tonight the moon in some fashion will come out;

That cold water is good to drink.The way taste slows a thing

On its way into the body.Light, widened and slowed, so much of it: It

Cannot be swallowed in the mouth of the eye,Into the throat of the pupil, there is

So much of it. But we let it in anyway,Something in us knowing

The appropriate mechanism, the moment’s lever.Light, the slow movement of everything fast.

Like hills, those slowest waves, light,That slowest fire, all

Confusion, confusion hereOne more part of clarity: In this light

You are not where you were but you have not moved.

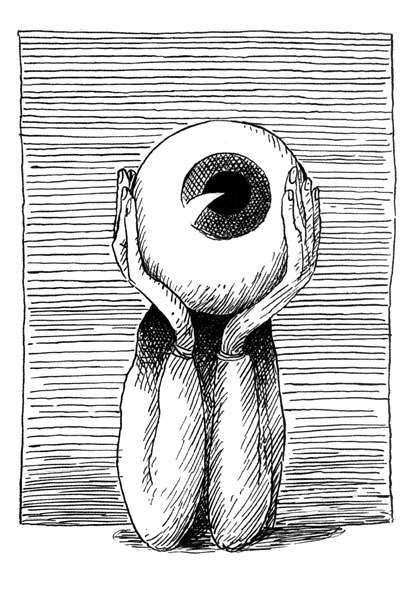

Drawing (2012) by Selcuk Demirel, from Cataract by John Berger.