I’ve always been obedient to a fault. When I competed in the Sonoma County Oral Language Fair in third grade, I foolishly omitted stanza four of T.S. Eliot’s “Macavity: The Mystery Cat” during my recitation:

Macavity, Macavity, there’s no one like Macavity,

For he’s a fiend in feline shape, a monster of depravity.

You may meet him in a by-street, you may see him in the square—

But when a crime’s discovered, then Macavity’s not there!

No master of deceit myself, I was consumed by the fear that I had lied to the judges and duped them into believing my performance flawless. Before I left the classroom where the competition was held, I approached the judges’ table and confessed my shameful slip-up. One of the men on the panel, the vice-principal of my elementary school, said, “You shouldn’t have told us.”

My best friend growing up, though, she was always a little bit bad,* charming me with her calculated disobedience, the kind of girl who would lead me out to the far corner of the field behind the playground and tutor me in swear words. She tallied on her fingers what she knew: bullshit, bastard, little fucker, dipshit, etc. The kind of girl who, a few years later, would invite me to pour a box of laundry detergent into the fountain at the center of the town square. And a few years after that, I’d skip first period with her, hide a bottle of vodka behind a bush in the park, smoke sweet and slender cigars on the hill behind her house, and assist her in orchestrating a fool-proof biology-quiz-acing scheme. For years, we claimed each other as best friends, a designation that carried with it the weight of exclusivity, the security of loyalty, and the promise of the slight transgressions I was too nervous to crave—let along think-up and execute—on my own.

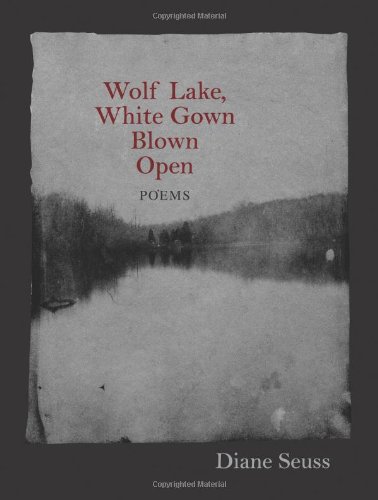

The poetry I love most, I love the way I did this girlhood friend. And for the same reasons: disobedient wit, cool smarts, a throaty voice, candor. I love it for its intensity, for its invitation to intimacy. Take, for example, “Song in my heart” by Diane Seuss” ** (which can be found in Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open, a book that secured a permanent place in my personal canon upon a first read):

If there’s pee on the seat it’s my pee,

battery’s dead I killed it, canary at the bottom

of the cage I bury it, like God tromping the sky

in his undershirt carrying his brass spittoon,

raging and sobbing in his Hush Puppy house

slippers with the backs broke down, no Mrs.

God to make him reasonable as he gets out

the straight razor to slice the hair off his face,

using the Black Sea as a mirror when everyone

knows the Black Sea is a terrible mirror,

like God is a terrible simile for me but like

God with his mirror, I use it.

In another poem from Wolf Lake, “The cooked goose,” Seuss asks, “Have you developed some sort of affection // for me as your eyes weaved down the page?” Yes, deeply. And along with it, a desire for transgressive, powerful, and heartening disobedience—disobedience Seuss transforms into craft, into poetry, into art, into questions that thrill and comfort and inspire. “Could you say you love me?” she asks. “At least for my flaws, / for my willingness to let all my seams show?”

* Read some Bad Girl Poetry here, courtesy of Claire Skinner.

** See Ann Marie Thornburg’s post “A Poem For Every Occasion” for more on Diane Seuss.