I. Beginnings

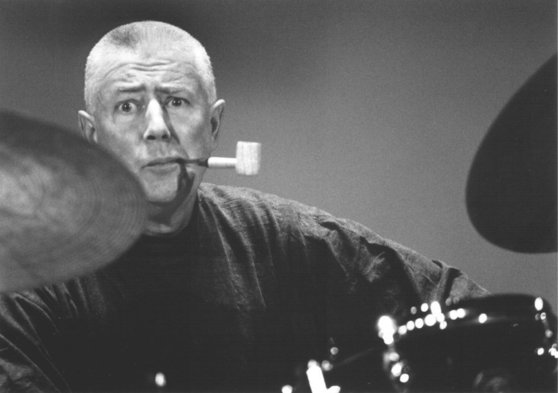

For a few minutes after we arrived at the room marked Rehearsal Hall, we weren’t sure that we were in the right place. We had come, my friend and I, to watch Dutch jazz drummer Han Bennink conduct a master class for University of Michigan music students. People carrying instrument cases seemed to be coming and going; others, like us, loitered uncertainly in their winter coats. At the center of the chairs and music stands scattered around the high-ceilinged Hall was a drum set: a reassuring sign. And then, like an overture to the group improvisations we would spend the next two hours watching, things began to take shape out of the confusion. A few bold loiterers dragged some chairs into two semi-circular rows. Student musicians set music stands in place and started unpacking their instruments: upright basses, saxophones, violins, a trumpet, a guitar, a harp. Finally I spotted the face I’d studied in photos online: reddish cheeks, close-cut white hair.

“I think that’s him,” I told my friend.

“Then I guess we’re in the right place.”

II. Question and Answer

It turned out, once everyone was seated and ready, that with Bennink had come one of his collaborators, violinist Mary Oliver. A dynamic, almost good-cop/bad-cop, quickly developed between the two musicians. Just as she set her violin against her neck to begin the first part of the master class, a duo performance, he turned away from the drums to solicit questions from the audience. Oliver’s sly exasperation with her partner suggested that she was used to his misbehavior. “I have a good joke,” he said suddenly. “Do you want to tell it?” she asked. Without answering, he struck the snare drum, and they began.

The type of music Bennink and Oliver play has only a tenuous relationship with the jazz most of us are used to. While Bennink’s range as a drummer is often noted and praised—he has backed mainstream legends such as Wes Montgomery, Dexter Gordon, and Sonny Rollins—he is best known as an avant-garde musician joining forces with other “out” heroes like Peter Brotzmann, Evan Parker, and Derek Bailey to push jazz to its limits. Oliver, who holds a PhD in the theory and practice of improvisation, has played with, among others, the Nieuw and SONOR ensembles, as well as the Instant Composers Pool, alongside Bennink.

So before taking questions, they played two short pieces. While Oliver’s playing was sensitive, intelligent, and impressive, Bennink was the real spectacle, demonstrating a number of the surprising and funny techniques unique to his playing. He laid towels over the drumheads to dampen the sound, then took the towels off; he licked his thumb and dragged it across the head of his floor tom, making the drum groan; he employed a variety of drumsticks and brushes, at one point upending a bag of them over the kit, at another point throwing his brushes into the air, then jumping up from the drums to retrieve them; he played the snare with the heel of his boot pressing into the drumhead, then played the boot itself. He stuck the butt of one stick inside his cheek and then tapped the projecting end with the other while singing. But Bennink’s antics weren’t all flash and dazzle. He listened to his partner and responded in his own voice, holding up his end of their inventive dialogue.

During the actual Q&A, Oliver talked about her collaboration with dancers, while Bennink told how his family was too poor after World War II to buy a drum set, so he played on the kitchen chair. He agreed with Oliver that improvisation is very much a discipline, though he noted too that he sees written music as nothing more than “flypoop on white paper.” Early on, he told us, he had idolized the drummer Kenny Clarke, before realizing that he wasn’t Kenny Clarke. “You are who you are,” he said, “and you have to deal with that stuff.”

III. Rolling Duos

After asking their questions, the students had the chance to play with the guest performers. In a system called “rolling duos,” two students at a time would improvise with Bennink and Oliver. If one of the students stopped playing, another from the semi-circle would take their place, until they had all had their turn. To me as a viewer/listener, the ways in which Bennink, Oliver, and the students talked about their playing were just as interesting as the playing itself. The vocabulary they developed to discuss the rolling duos seemed to me more social than musical: the UM professor-host urged his students not to be afraid to “elbow in”; Oliver critiqued one violinist for being “too polite” and not asserting herself; Bennink said, “To be rude—that’s musical.”

IV. Floppy

Yet at other points in the master class, such as during the student-only small-group improvisations that followed the rolling duos, some musicians were called out for insensitively interrupting others. There was talk not of notes or rhythms but of roles, and one bassist reflected that falling into her instrument’s conventional supportive position made her uncomfortable. Hearing these types of performances, which are often challenging in their abstract complexity, framed in this familiar human context made them more accessible to me. The stage became a little society: instead of talking to one another, the participants expressed themselves through their jazz instruments. No doubt each musician’s on-stage personality had something to do with their off-stage one, as Oliver was serious, thoughtful, and at times controlling with or without her instrument, or as Bennink’s playing was as unpredictable and funny as his speech.

Oliver and Bennink took turns grouping the students into quartets for improvising. Once, Bennink pointed to one of the saxophonists and said, “What about you, floppy?”

“Did you say floppy?” the student asked.

“He calls everyone that,” Oliver put in. “It’s a term of endearment.”

“No,” Bennink said. “It’s a coarse name.”

V. KRAALOOG

Near the end of the master class, Oliver distributed sheet music to the students; from where I sat in the second row, I could see the word “KRAALOOG” across the top of the page. The piece consisted of six numbered rhythms, and each rhythm consisted of two undetermined pitches—it was up to each player, Oliver explained, to choose his own. After practicing each rhythm as a group, “KRAALOOG” began, Oliver holding up whatever number of fingers (thumb for 6) corresponded to the rhythm they were all to play. As the group went through the rhythms, according only to the order Oliver chose, she walked around the semi-circle, signaling with her hand for certain people to drop out altogether and others to improvise against the rhythms. Sometimes she brought everyone up in volume, other times she brought everyone down. Sometimes she tried to shut someone off, but they couldn’t see or hear her because they were playing with their eyes closed. When the piece was over, I was stunned. It had seemed to breathe, spinning its numberless variations on the fixed center of rhythm.

“So what does ‘KRAALOOG’ mean?” someone asked.

Bennink began to answer, but Oliver interrupted him. “It means beady eyes.” Bennink went on anyway. The piece’s composer, Misha Mengelberg, had written it for him. “I’m an old pothead,” he said, “and when I smoke, my eyes get glittery.”

VI. Last Date

The morning after the master class, I was sitting at my usual coffee shop when Han Bennink and Mary Oliver walked in and sat down. Could that really be them? It seemed impossible, perhaps in part because I had just started to listen to Eric Dolphy’s Last Date, which features Bennink on drums (and Mengelberg on piano). But Oliver had a small instrument case in her hand. While she ordered, Bennink sat at the table. I couldn’t resist watching him as he licked his thumb and rubbed a scratch on his leather bag. When he was done with that, he began tapping the tabletop lightly with his fingers, the way anyone might. I sat there anguishing over whether I should thank them for the master class or leave them alone. Eventually they finished their breakfast and used the bathroom. Then they were gone, but Last Date kept playing.

The morning after the master class, I was sitting at my usual coffee shop when Han Bennink and Mary Oliver walked in and sat down. Could that really be them? It seemed impossible, perhaps in part because I had just started to listen to Eric Dolphy’s Last Date, which features Bennink on drums (and Mengelberg on piano). But Oliver had a small instrument case in her hand. While she ordered, Bennink sat at the table. I couldn’t resist watching him as he licked his thumb and rubbed a scratch on his leather bag. When he was done with that, he began tapping the tabletop lightly with his fingers, the way anyone might. I sat there anguishing over whether I should thank them for the master class or leave them alone. Eventually they finished their breakfast and used the bathroom. Then they were gone, but Last Date kept playing.