In my early twenties, I made a concerted effort to stop calling myself a ‘girl’. Although ‘woman’ never quite felt like it fit, I insisted on the distinction. I willed my speech and manner to embody the word, desirous as I was to shed all associations with the mewling, coy, and flighty thing I believed ‘girl’ represented and meant.

There were ways in which this linguistic adjustment empowered me, but it also simplified my perspective and understanding of identity and relationships. As a ‘girl’, it was all too easy to pitch my voice high and thin, to make myself seem smaller, and lighter—and so too were the things I said, made less, and small. However, as a ‘woman’, I was able to convince at least myself that what I spoke carried their own weight. Years enough have taught me that misogyny doesn’t distinguish between the two, and I’ve come around to recovering the complexities and useful darknesseses found within that idea of ‘girl’.

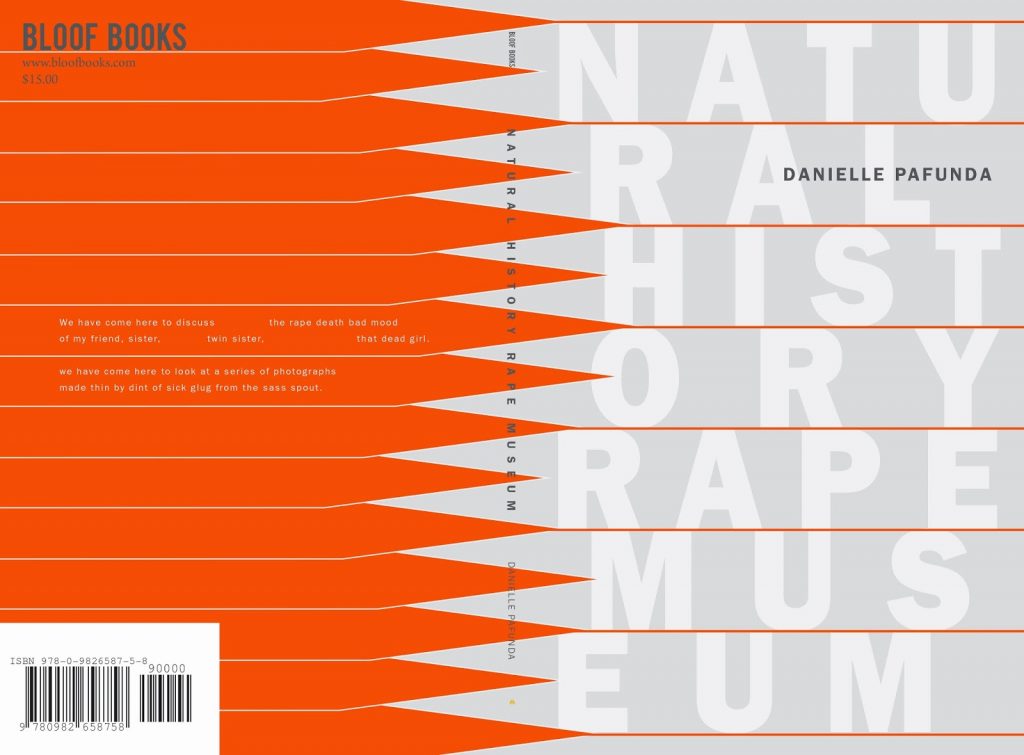

Among several poets I consider to be writing towards this recovery is Danielle Pafunda, whose newest book, Natural History Rape Museum, was released just last month by Bloof Books. In an essay for the feminist issue of the literary journal, Volta, Pafunda writes:

Girl is a category that the patriarchy has deigned to construct in only the broadest strokes. In refusing to become woman, in continuing to become or occupy the category girl there may be some radically subversive potential. […]

The girl is uncultured and unrefined, crude and raw (though like much raw food, teeming with live active cultures, possessed and pungent). Let us be very clear. The girl I once was burdens me. I spend a great deal of time bleaching her out. She makes us vulnerable and ruins every day of our life. Though her shame frequency cannot be overwritten, it can be mined, directed, and amplified.

Upon re-readings of NHRM, it was to this lens I returned, integrating my impressions and feelings into the larger, ongoing dialogue of feminist poetics, to the idea of voice, and the frequencies we emit and receive.

One such frequency may be ‘Gurlesque’, a word that stitches together Riot Grrl, grotesque, and burlesque, and names a loose confederacy of aesthetic sympathies and ideas, as well as an anthology of several contemporary poets.

I admire much of work associated with the Gurlesque, and, for all the reductive tendencies of literary movements and other types of branding, it helped cast a critical light on a lot of excellent ill-mannered, and riotous poetry. I’m a fan of Pafunda’s work in particular (included in this anthology), and appreciate the cruelty of her playfulness, her girlish macabre veering into full-on demented—qualities that are realized by the high artifice of her poems.

To illustrate what I mean by this sense of artifice, I’ll cite another poet of the Gurlesque, Chelsey Minnis. To those unfamiliar, I direct you here, here, and here. As a point of stylistic comparison: a line of Minnis’ may find its resonant turn in a deceptively plainspoken metaphor which opens out to a moment of stark sincerity; a line of Pafunda’s would more likely draw intensity from a disjunctive, almost schizophrenic syntax, and a concussive sequence of highly alliterative and surreal words and images. This is a generalization, of course, but useful in aiding my attempt to describe her poetry’s effect—that is, reading her feels like entering into a nightmare which you know in your blood has something very frightening and true to tell you.

I remember first hearing about this most recent collection, and thinking that there are a handful of words in the English language I’m averse to. The word ‘rape’, no matter how mundane or clinical the context of its appearance, elicits a visceral and instantenous reaction. There are some words, when said over and over, that grow strange in one’s mouth, and over several permutations cognitively disintegrate into their discrete phonemes, their noises. Rape is not one of those words; it has the brute integrity of fact, insoluble and fixed. Upon reading these poems, I imagined that word—its hardness, a high stone wall— and thought that this is what language might sound and look like when hurled against it.

There is less narrative architecture in this collection than in Pafunda’s two books immediately previous, Iatrogenic/their testimonies, and Manhater, but what she loses in a cohesive thread of a premise (dystopic feminist future in Iatrogenic), or character (Mommy V in Manhater), she gains in the detachment and disorientation necessary to fathom a larger project. That is, Pafunda’s last three books taken together seem to arc into a project resolutely committed to excavating the feminine voice from (and out of, and through) extreme states of power and powerlessness.

Informed by the book’s title, the feminine psyche these poems manifest reads as much forged from, as harrowed by, trauma and institutional violence. As a museum of natural history would collect and curate objects, contriving dioramas and presentations of mankind’s culture and development, these poems can be read as an attempt to outline an alternate or adjacent anthropology, one whose landscapes and relics are interior and subjective.

The first poem begins in the womb, and from the outset we encounter Pafunda’s typographical decision to contain the title in a box placed in the middle of the poem’s text.

The gesture repeats for several poems in the book, and the visual disruption is both minor and significant. Even as I scan from left to right the interrupted line, reading around or over the box, I am made aware of how I am choosing to dismiss or incorporate its intrusion. In lieu of a single interpretation, I offer the following scenarios:

The gesture repeats for several poems in the book, and the visual disruption is both minor and significant. Even as I scan from left to right the interrupted line, reading around or over the box, I am made aware of how I am choosing to dismiss or incorporate its intrusion. In lieu of a single interpretation, I offer the following scenarios:

– You are in a gallery and a painting’s title placard hovers in front of the image, or, the curatorial text contains neither title nor the material used in the piece, but a fragment of the artist’s thought instead.

– You are in a waiting room. All the adults, out of tacit politesse, are hushed, when a little girl’s very loud voice breaks through the quiet. As can be expected of children’s outbursts, what she says may be heartbreaking, or absurd, or morbid but, but it’s first of all, alarmingly honest.

– You are watching a foreign movie in a language you are just beginning to learn, and the subtitles appearing beneath it do not translate the dialogue occuring before you, but instead narrates a parallel fiction as it is being conceived by one of the characters in the movie.

It is at this depth of uncanniness that Pafunda operates, assembling, as she states in the second poem, a “herniated memoir” with “Fat needles, huffer glue, soap scum fingernail // scraping through the bandage.”

In the section titled “On the Bear Skin Rug in Front of the Fire I Construct the Following Tableau”, Pafunda curates a sequence of nightmare visions. It opens with a poem conjuring the grandmother figure from Little Red Riding Hood, and relates a scene that feels both cartoonish and oracular. Another poem contains the image of “two criminals arranged as one body”, in a line that reads as syntactic ouroboros, circling back in on itself, and performs as much as observes the nature of complicity—a literal physical entanglement. Each of these visions end with the same narrative cue, which one cannot help but read as a means to ground or orient. The cue, however, functions otherwise. It estranges and disquiets, and is another example of how Pafunda, guided by a keen sense of artifice, crafts madness into something lucid.

The poems in the following section offer a formal reprieve from those preceding and immediately following. They comprise a traditional museum exhibit and includes poems with titles like “Wolf Spider”, “Fox”, “Stingray”, “Cord of Wood”, “Fish”.

From “Pearl”:

Permanent prenatal nimbus,

whack-skulled and coreless.

A dim sob, your patina. Ductless.

Weep not, but swoon. Adored solder,

head-drilled emissary.In the privilege tents, you cauterize

a prosthetic heart and fibrillate.

These play a terrific and terrifying music (hear those back-of-the-mouth, choking fricatives in “whack-skulled and coreless”, the plosives of “dim sob”, “patina”, and “ductless”), and the relative smoothness of its syntax conveys violence in stillness, a skilled taxidermy, and the predators under glass.

I’ve neither the space nor the gall to test a reader’s patience by going over each of the poems of this book, so I’ll just note that the last two sections, in particular, are astonishing. It’s appropriate that section four should begin with a poem titled “Punishment”, for what follows in the next several pages are indeed, unrelenting in the violence Pafunda’s language enacts. From “Whichever Pen You Use to Sign, Your Own Blood Issues”, listen to the brokenness:

stumper cesspool torquing slack bastion cracks wide.

I hoof it through Ugly Park to the fixit. A salve please,

an antibacterial spill theorem. Freak tag my chart please,

my lick please, my rigged stop heart thwack. Slushing

Even to those who aren’t writers and daily fret or obsess over the myriad ways in which a thing can be said, the concept of “voice” pervades living. It’s cultural shorthand for personal agency, and contains in its utterance all the senses of being acknowledged and heard. Voice is a visceral idea: the command of another’s attention, instantiated through vibrations in folds of membrane stretched across the larynx. In poetry, voice becomes a transaction of attentions, and those acquire depths of murk and light through any number of formal and lingustic considerations.

Danielle Pafunda’s Natural History Rape Museum is a difficult and disturbing work, which exacted aesthetic and emotional violence upon my attentions. To then say I enjoyed it immensely may seem a perverse claim, but it’s nevertheless true. It recovers, for me, something of the ‘girl’—a rage just beneath and becoming, all that light and shimmer.