Browsing Netflix recently, my partner and I decided to watch Kon-Tiki, a movie about Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl’s 1947 raft excursion across the Pacific Ocean, from Peru to Polynesia. About fifteen minutes in, my partner said, “I don’t think this movie is going to pass the test.”

“What test?” I asked.

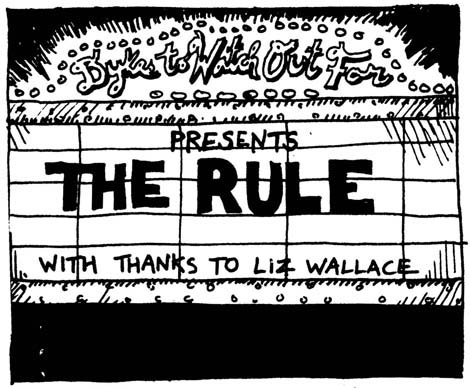

She was talking about the Bechdel Test (a.k.a. Bechdel/Wallace Test, Bechdel Rule, or Mo Movie Measure). To pass the Test, a film must satisfy a very simple set of criteria: (1) it must have at least two female characters, preferably named, who (2) talk to each other about (3) something other than a man. A cartoonist best known for her graphic memoir, Fun Home, Bechdel outlined the Test (“with thanks to Liz Wallace”) in “The Rule,” a 1985 installment of her Dykes to Watch Out For comic strip.

Whether or not a film passes the Bechdel Test (or how many of the three criteria it meets) is one way of measuring how responsibly it depicts women as fictional characters. Of course the Test isn’t perfect—a film that fails it still can challenge the varied damaging representations of women that have been naturalized by decades of commercial filmmaking. (For an exciting and frustrating curveball of a female protagonist, check out Barbara Loden’s Wanda, 1970). Similarly, a piece that passes the Test is by no means necessarily “feminist-friendly.” Ever see that commercial for Cascade Platinum dishwashing detergent, where two women bicker about each other’s dishwashing habits, prompting the intervention of a third woman, the Cascade Kitchen Counselor? (Why is there a website where you can isolate and watch terrible off-air commercials? And why, oh why, does someone named Patrick Ney comment at the bottom: “This is a great commercial!”?)

And remember that by relying on racist, classist, homophobic, and ableist stereotypes and half-assed or otherwise unscrupulous characterizations, films that pass the Bechdel Test can still reiterate and reinforce harmful assumptions about people in our world. Kon-Tiki is unlikely to pass some of these other tests as well. In one early scene we see Heyerdahl and his wife, Liv, in Polynesia; she’s weaving baskets with the native islanders while he reads. “You’re going to make this place famous,” she tells him. He looks up from his book and answers: “When people hear of Fatu Hiva, they will think of Thor Heyerdahl.”

Yet despite its limitations, the Bechdel Test effectively highlights some of the ugliest yet most invisible truths about the movies we watch. For example, that strong female characters are a minority in film. I don’t mean “strong” as in capable and empowered, etc. (though that’s true, too), but as full and real fictional entities. Characters shaped around traditional and clichéd types, characters defined primarily by their relationships to other characters—these kinds of characters fall flat on the screen not only because they fail to provide the illusion of “realness” we require in representational narrative art, but also because they fail to activate our powers of empathy. (Remember the controversy surrounding Breaking Bad’s Skyler White?) Sure, every movie is going to have major characters and minor characters, and we do often understand minor characters through the roles they play in main characters’ lives. And yes, there are narrative conventions regarding point of view that sometimes confine us to the protagonist’s perspective. But the failure of so many films to meet the criteria of the Test suggests that far too few films take on protagonists who are women or female points of view, using women more as passive set pieces than as drivers of action. Thus far too few films ask us to care about or even consider female characters. Apparently they aren’t as interesting, or as lucrative.

So in Kon-Tiki, for example, Heyerdahl’s wife, Liv, gets only about ten minutes of screen time. Of course this movie is an adaptation of a memoir about European scientific adventuring, a world—like many of the worlds that make entertaining cinema—dominated by men. In three scenes we see Liv back in Lillehammer, Norway—twice on the phone with her husband, once being photographed for the newspaper with her children. While we watched the ever-more-ragged men on their raft, we wondered what was happening with Liv. They could have done a lot more with her, my partner suggested. “But that’s not the story they wanted to tell,” I replied—a statement that began as a mindless defense of the film (why?) but that has morphed into a shorthand, for me, of the implications of the Test. There are stories they want to tell, and stories they don’t want to tell. Most often, the stories they want to tell are the stories about men, and the ones they don’t, the stories about women.

I said that the ugly truths the Test dredges up are invisible, too. When my partner first told me about the Test after reading an article about Swedish cinemas incorporating it into their rating systems, I was amused to think of waving goodbye to the few stupid macho-man movies that wouldn’t survive this latest stage of cultural evolution. But the more we discussed it, the more we were unsettled to realize how few of the films we’d watched and enjoyed over the past year—many of which can be found in such canons as the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 greatest American films—could pass the Test. How do the AFI’s top three fare? Citizen Kane, Casablanca, The Godfather: fail, fail, fail! The reason the Bechdel test has been called “eye-opening” (and has been for me) is because it allows you to see what was hiding right there in front of you, on your screen.

Still, for all my talk about the Bechdel Test, I forgot what it was days after learning about it. “What test?” I asked my partner. While I find this slip both shameful and embarrassing, I’m glad at least that it provides me with an example of privilege in action, my own privilege. And to think it had been around since before I was born, yet I’d succeeded in avoiding it until now—and naturally I thought because I’d just learned about it that must be very recent, perhaps even “trending”! But why should I notice anything awry when nothing seems to be, when the movies I watch speak to my experience as a male viewer? But they don’t, I’m understanding again and again, every time I pit a movie against the Test and it fails: they don’t actually speak to my experience. Because there are more than two women in my life, and they talk about things other than men. To say the least. Thank God.

* * *

As I said, even though these problems remain relevant and urgent to me and others, “The Rule” and the Bechdel Test are not new and have accumulated an orbit many critical elaborations, analyses, and embellishments. Please explore some of them:

The Bechdel Test Wikipedia entry

The Bechdel Test for Women in Movies video on the wonderful Feminist Frequency site

The Bechdel Test Movie List, where you can search an archive of over 4,500 films to see if they pass the Test

Ten graphics for the Bechdel Test

The Female Character Flow Chart

This article on the Russo Test for LGBT movie characters