Sometimes a book comes along that is so beautiful and necessary that you wish you had written it yourself—if only you had been smart, resourceful and determined enough. For me, Infinite City is that book. Part atlas, part essay collection, Rebecca Solnit’s 2010 examination of San Francisco from many angles and with the help of many hands made me think more deeply not just about that particular city, which I love and where I’ve been fortunate to spend time as a writer, but also about other cities that I’ve inhabited, even briefly. I like to read portions of it to unsuspecting college students, to challenge their perspectives, say, on a sleepy Friday morning; or just keep it on my desk because I believe that being in the presence of a book like this will make them better citizens. (Jury’s out.)

So I was very pleased to see the appearance of Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas, Solnit’s newest book, edited with New Orleans native Rebecca Snedeker and again employing the talents of mapmakers, essayists, book designers and other people who remind us just how many different expressions of intelligence exist in a great city. These are books that seek not to define the cities that are their subjects, but rather to undefine them, to open them up to many ways of seeing without claiming them definitively for one particular population or viewpoint. Solnit and Snedeker find their central metaphor in the title: “New Orleans is all kinds of unfathomable: a city of amorphous boundaries, where land is forever turning into water, water devours land, and a thousand degrees of marshy, muddy, oozing in-between exist.”

With its hands-on aesthetic, odd trim size, and sense of community, Unfathomable City feels like resistance to current trends in publishing toward mass appeal and digitization. Solnit and Snedeker are clear in their suspicion of modern technologies such as Google maps, at least in regards to how we use it to interact with our spaces: “The problem with these technologies is that though they generally help get you where you’re going, that’s all they do. With a paper map, you take charge….A map shows countless possible routes; a computer-generated itinerary shows one.” The difference is one of human agency: “When you navigate with a paper map, tracing your own route rather than having it issued as a line, a list, or a set of commands, you incrementally learn the lay of the land.”

It is a powerful vision of being an active observer and learner. But there are places even beyond the map, as Solnit and Snedeker acknowledge. As you learn your way, they write, the map is “no longer on paper in front of you but inside you….You become a map, an atlas, a guide.”

I live each summer in Tel Aviv, the young city, much younger than both San Francisco and New Orleans, whose street map I wrote about earlier this year. But I dabble in Jerusalem. Each summer I travel there at least once, typically with my young son, who is drawn to the Old City and its spiritual spaces.

The map of Jerusalem is famously indirect, gnarled by history and shifting borders and a confounding bureaucracy that answers to many masters, many of them long dead. I have never fully mastered it. Even when I lived in Jerusalem for a period of several months some years ago, I only knew my most common routes, the ones that I walked every day. (This was still the era of bus explosions, and I rode the bus only on Friday afternoon, carrying groceries back from the shuk.)

But this summer, when my son asked to visit the Temple Mount, also known as Haram al-Sharif, I decided to do without the map altogether. At some point you want to leave the tourist in you behind. We left our Tel Aviv apartment in the early morning amidst the dog walkers, and joggers, and made our way to the Central Bus Station, where we grabbed a sherut and tried not to feel too sick as the stuffy shared minivan climbed the winding highway to Jerusalem.

Following the consensus of the passengers—I was too nauseated to make my case in Hebrew or English—the driver emptied us out a few blocks north of Damascus Gate, where the bowl of Jerusalem tilts toward the Old City. There are in fact many Jerusalems, just as there are many San Franciscos, except more so, and here all the shop signs were in Arabic and old buses queued to take travelers into the West Bank.

With the Old City walls ahead in the distance, and the slight decline in the streets pushing us downhill, we found our way to Damascus Gate; then we were inside. The first step into the Old City is always astonishing to me—one moment you’re outside, and then you are on the other side of all those walls. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has created border crossings and checks everywhere, it seems—you even get wanded at the entrance to the mall—but you can walk through any of the great gates to the Old City free and easy as you like.

We bought a peach and a doughy bagel buried in sesame seeds from a street vendor. We conducted this small transaction in English, except for the unnecessary, and possibly unwelcome, shukran I added at the end to express both gratitude and to say I belong here, too, just a little bit. Then we turned and headed toward the entrance to the Temple Mount.

It was an unfamiliar direction from which to travel though the Old City; more commonly I’ve entered through Jaffa Gate, with its giant space for tourist buses, or the smaller, more intimate Lion Gate, with its famous bullet holes. But the current of foot traffic was moving in the direction of the shuk, right in the middle of the Old City, and all we had to do was be sensitive and follow it. The warren of the market itself can be disorienting, even for seasoned Jerusalemites, but there I saw a young Hasid with his distinctive black hat and coat, and knew he must be heading toward the Jewish Quarter for morning prayer, and we walked along behind him at a discrete distance, both with him in that space and not.

Language, history, even prayer times: these are all maps of Jerusalem, sources of conflict and crucial information. As Rebecca Solnit writes in Infinite City, identity is contingent along these map lines, and can shift neighborhood by neighborhood or even at each street corner. In the Muslim Quarter we were English-speaking Americans; as we left the shuk and entered the Jewish Quarter we became Hebrew-speaking Jews. My son took his kippah out of his pocket and put it on his head. (He senses signals of his own.) But soon we were in line to ascend to the Temple Mount with the rest of the tourists, and I asked him to take it off. Better to be blank Americans again.

It was still early morning, but the sun was uncomfortably warm as we queued amongst the British and American tourists, who came equipped with heavy cameras hanging from both back and front, and with more water bottles than a marching battalion. A different procession of Americans passed by us, these with kippahs on their heads and sandals on their feet, singing and clapping and escorted by a very amateur saxophone, on their way to celebrate a bar mitzvah at the Western Wall. Just another Thursday in Jerusalem.

Then the line moved and we climbed the wooden snake bridge that angles alongside and then above the worshippers down at the Wall, and then, like so many spaces in the Old City, there is a narrow passageway and then an entrance and then you are there.

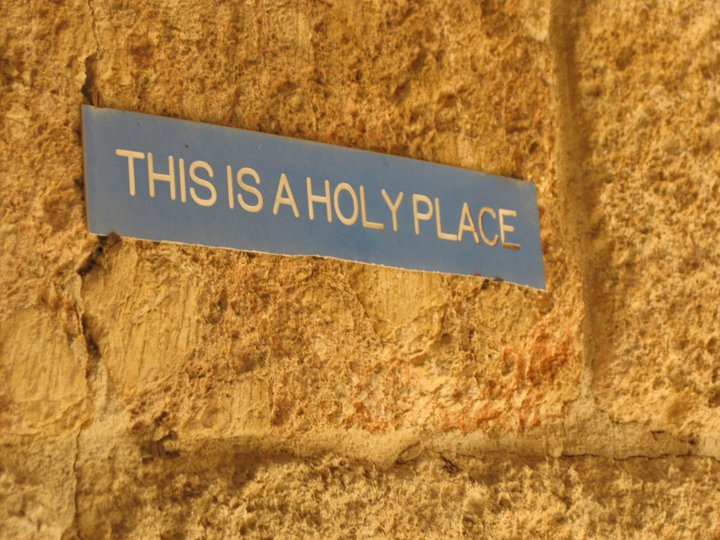

The Temple Mount is huge, much bigger than anything else in the Old City. There are great open plazas and few structures and—also unlike the rest of the Old City—gardens and trees and plenty of space for idle walking. And yet for all its openness it is clearly divided. The two great buildings, the golden Dome of the Rock on one end and the dark Al-Aqsa mosque at the other, are off-limits to non-Muslims, with a man politely but firmly denying entrance in front of each. The rest of the space has its own geography, expressed in age and gender. Women and small children picnicking in the shade of the mosque or on a staircase. Men studying in a small circle of chairs underneath a tree. Wide spaces in between so that these groups did not intersect.

Without a map or guidebook my son and I wandered free of ghosts and history. After a few minutes we descended a set of beautiful stone steps into a green garden and stumbled upon a group of teenage girls engaged in the gossip of the modestly dressed. This particular section of the park was their space, and they let us know it with their instant communal silence and sidelong glances. My son and I gathered up our foreignness and our maleness and turned back the way we came.

The mid-morning Jerusalem sun had gotten very warm and the population of the Temple Mount was growing and moving, slowly but perceptibly, toward prayer time. We walked down and out and into the busy shuk and out of the Old City itself and onto a sherut once again, and then we were driving back down the curling mountain highway toward the west and the ocean and the salt air and Tel Aviv.