I am at the tiny police base in my parents’ neighbourhood in Kuala Lumpur. I’ve come to report the loss of my Identity Card, a document Malaysians must carry at all times. An Identity Card bears your name, photograph, and I.C. number, under which your race and religion are listed in the records of the National Registration Department. When applying for an I.C., you can choose from a menu of options for Race (Malay, Chinese, Indian, Other) and Religion (Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, Christian). When I am asked to specify my race — to sign up for a bank account, to see a doctor at a clinic, to rent a mobile USB modem, to do anything at all, in short — I say “Malaysian,” but on my Identity Card I am Indian. “Malaysian,” despite the government’s “1Malaysia” propaganda campaign — One Race, One Nation! rejoice the posters and the songs — is not a National Registration Department category. If you’re of mixed race, you are assigned the race of your father, unless one of your parents is Malay. The child of a Malay parent is Malay, and all Malaysian Malays are legally Muslim. If you are Muslim, your Identity Card photograph is captioned “Islam,” to facilitate the enforcement of Shariah law. There is no option to call yourself an atheist on your Identity Card. The first principle of the Malaysian National Pledge is belief in God. When I’m asked my religion, I tell the person filling out the form, “Anything also can,” a Manglish phrase that perfectly conveys my lack of investment in the system, my refusal to play the game, and even, given the right interlocutor, my godlessness.

On the police base television, two Islamic scholars are discussing a surah of the Quran. The young constable on duty sits facing the TV, his back to a large poster that advises: “KEEP AWAY FROM SHARIAH CRIMES: SODOMY, PROSTITUTION, ADULTERY, FORNICATION, ALCOHOL, GAMBLING.” The poster is illustrated, the last two crimes clearly depicted in the foreground against a shadowy background of faces and bodies in ambiguous positions.

The constable tells us he must consult his supervisor. As he opens the door to his supervisor’s office, my father — hard of hearing, and never the most tactful person — says loudly, “The fler sleeping inside there.” So many layers of this half-joke would be opaque to an outsider: the cliché that Malays, in particular Malays employed by the government over better qualified, more capable Chinese and Indians, are pathologically lazy, that they will do anything — nap, snack, chat on the phone — but the work for which they’re paid.

It has been twenty-one years since I left Malaysia to live first in the US and then in Europe. I share with expatriates from all nations through the ages that peculiar disorientation that follows every homecoming: Is this really where I come from? Did I once belong here?

We like to believe we remember exactly who we used to be. But the truth is that I can no longer remember how much or in what ways my country infuriated me when I was ten, twelve, fifteen. I do know that I often felt I didn’t belong, though that probably had as much to do with temperament and personal circumstances as it did with any national narrative that excluded me. Now when I come home — I still think of it as home, though I’ve now lived elsewhere longer than I lived in Malaysia — I suffocate almost immediately under a drift of horrors, but which of these did I notice, let alone manage to articulate, when I lived here? Before I’d encountered real newspapers I would’ve been able to tell you that our press was heavily censored, but not that we have nothing that can honestly be called a press: our newspapers contain a mix of government propaganda, corporate press releases, and uneditorialised quackery.

Before I’d lived in cities with parks and libraries, I might have accepted Kuala Lumpur’s lack of public spaces, and the central role of shopping malls in the leisure time and social lives of its citizens, as a necessary byproduct of development. I might have been amused, rather than enraged, by the list of things middle-class families supposedly cannot live without in this city: at least one car for every adult member of a household; air conditioned bedrooms; live-in domestic help — glorified slaves — brought in from poorer countries. Before I became a parent, I might have vaguely registered the fact that in every other place I’ve lived, children are known to be happiest when they have regular access to the outdoors; now, having two young children of my own, I cannot imagine living in a city where children must — or so they are told — stay indoors to avoid sweating, mosquitoes, and kidnappers. As a teenager, I didn’t know that the kind of hearsay and scaremongering that surrounded me — they say, it seems, one taxi driver told me, they are coating the noodles in wax nowadays, they are boiling dirty underpants in the soup, they are making the laksa with old newspapers — was peculiarly Malaysian. I had not yet realised how strange and rare it is for the educated classes of any nation to lack basic critical thinking skills, a familiarity with the scientific method, or a fundamental understanding of statistics.

When I cast my mind back to the person I was twenty-two years ago, I do know this: the one aspect of Malaysian life that is most unbearable to me now, the primary reason I cannot live here or raise my children here, was a blur to me then. I saw only the stark outline of it, the superficial shape. The Malay girl on my bus who lined her hand with her handkerchief if she had to take something from a non-Muslim because the school Ustazah had taught her that non-Muslims were unclean; the Malay friend who was pulled aside and quietly chastised for sharing her water bottle with me after school, knowing that I could not be trusted never to have eaten pork; the titillating rumours about this or that canteen food being non-halal. I remember wishing things could be as they were in the stories of my parents’ generation, when people of all races used to eat in each other’s homes, when Malay men used to join their Chinese and Indian colleagues for a drink after work. But I didn’t understand the peculiar nexus of race and religion in Malaysia; railing against the incursion of racial categories into every sphere of life, I didn’t see how crucial the alliance of church and state is to the survival of Malaysia’s apartheid laws. Without state-sponsored Islam, the barrier between Malays and non-Malays would quickly become porous, as it was in the fifteenth century, when a whole new ethnicity was born of intermarriage between Malays and Chinese; the question of who is and isn’t Malay would reveal itself to be as complex as it actually is.

Others have deplored this state of affairs before me: it has become nearly impossible to call out Muslim theocracy without being accused of Islamophobia, or bigotry, or extreme conservatism. If I admit that I am unable to find beauty in the Muslim call to prayer — that, having heard it not only live from the local mosques five times a day throughout my childhood and adolescence, but also on TV, interrupting my afternoon cartoons, my seven thirty sitcoms, my parents’ nightly news, I continue to experience is as an intrusion, even an invasion, a proclamation of lordship — then perhaps you will sigh and say to yourselves, Ah, well, another one has sold out to the right wing. But I hear that call — its sounds, divorced from their meaning, so objectively beautiful — and all it says to me is: We own this space. For these few minutes, you will not be allowed to pretend that we share it equally; you will drop what you are doing and acknowledge our supremacy.

In the nearly twenty years since I admitted to myself that I don’t believe in anything supernatural, I’ve had to refine my stance on religion. At twenty, my atheism still a novelty, still an act of rebellion, I dismissed anyone of faith as an imbecile: how could any educated adult believe something so full of holes if it had taken me less than twenty years to see through it all? But life, if it doesn’t mellow you, does teach you that human beings do not operate purely on logic. Each of us abandons logic, consciously or otherwise, under different circumstances, but every single one of us abandons it daily. Why should faith be an exception? Most of my closest friends don’t believe in any standard version of God, but it’s possible for some kinds of faith to co-exist with a state of wonder and uncertainty. In the end, what I want from both my friends and my country is this: that their morality not be derived from a supernatural source; that their faith not colour their judgment of me; that their God not dictate their daily life or encroach upon mine. By all means give your God a room of his own inside your head, a room into which you do not invite me.

Keep your God out of our schools, our police stations, our televisions, our elections, and perhaps then — when Malaysia is the secular democracy, the model of supposedly “moderate Islam” that it claims to be — He and I will be able to co-exist on this green earth of ours. But these are impossible ideals. Even the moderate Islam that is the Malaysian government’s theoretical goal makes no attempt at a separation of church and state (“Faith and piety in Allah” is its first principle), and the whole point of Islam, as any practising Muslim will tell you, is that it governs every aspect of daily life; it is not just a belief system but a way of life. Though few will say so explicitly and on record, Islam is incompatible with modern, secular democracy — in very much the same way Christianity before the Reformation was incompatible with secular democracy — and that is the hard truth we have to work with. No war on terrorism, no Muslim fundamentalist bogeyman, no externally imposed interfaith dialogue can do the work of time. Religion — any religion — becomes compatible with modern life only when sufficient numbers of its adherents cease to believe that its scriptures are the unalterable, unequivocally binding word of God.

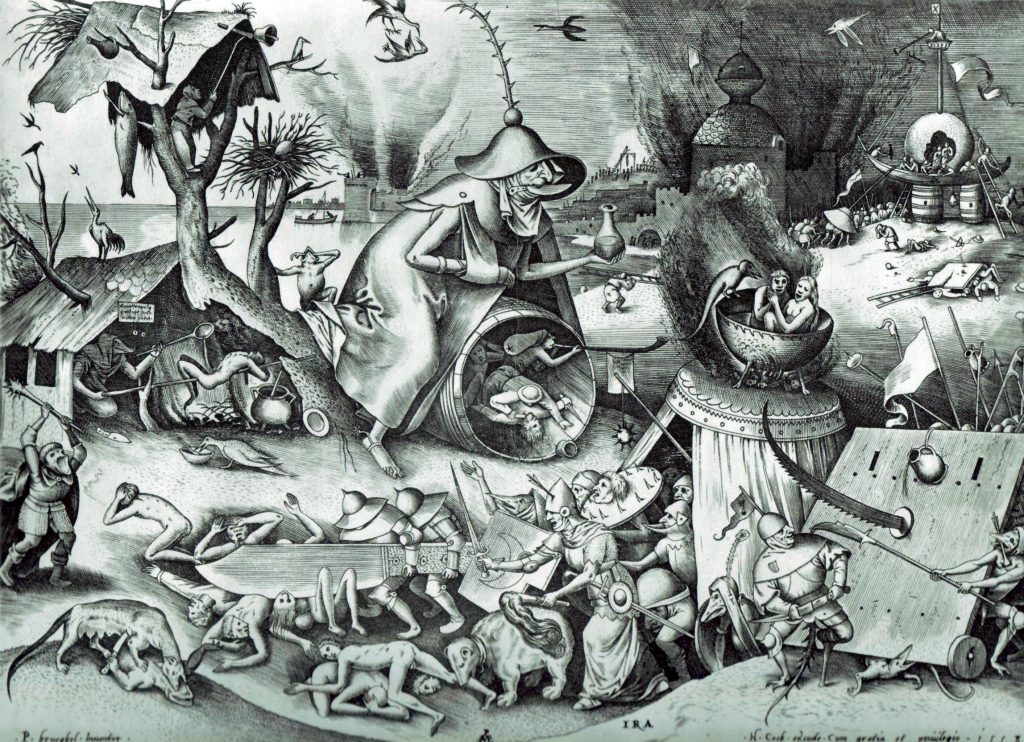

[Image credits: The Seven Deadly Sins, Pieter Bruegel the elder; “There’s Probably No God” poster from www.nogod.org.nz; “The Syariah whipping” poster from www.eperjuangan.com; portrait of James Joyce from www.poetryfoundation.org; “Quack Doctor or…” by Hans van Oort on www.trekearth.com; Willy Wonka “underwear soup” still from www.lostinthemultiplex.com; multiracial face from www.cornerstonesoup.wordpress.com; “Call to Prayer” from www.worldview.org; Charlemagne and Pope Adrian, Antoine Verard.]