The summer after I graduated college, I moved from central Virginia to central California to live in a stucco duplex in The Pocket, a neighborhood of Sacramento cradled in the crook of a river. The only person I knew there was my dad, and I spent most of my time at the public library trolling Craigslist for nannying jobs. During my ten months in The Pocket, before relocating to the Midwest to attend a creative writing M.F.A. program, the scope of my social and academic life narrowed suddenly and dramatically. I began to wake late and nap often, listless and uninspired, unmoored by the mundane content of my days.

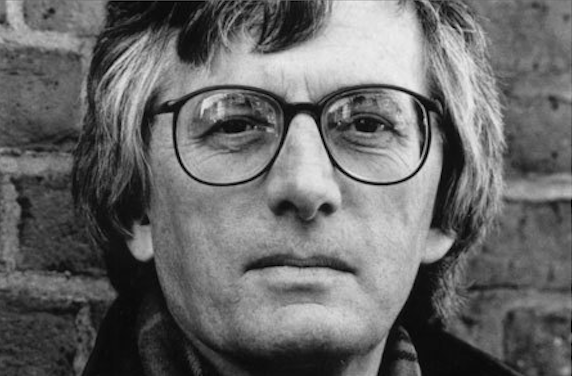

I longed for grounding, routine, and nourishment. In Sestets by Charles Wright, I found these things. I read it, reread it, reread it again.

And when rereading wasn’t enough, I disassembled every sestet in the book so that I might put them back together again: I translated each poem into its opposite, one by one, line by line. Some days, I would choose an antonym for each word of Wright’s, deferring any concerns of grammar and logic indefinitely, so ticking with unpaused breath became humming without stopped short-of-breath. Other days, I abandoned allegiance to Wright’s word choices and tried, instead, to rewrite the mood, feeling, or tone of the poem in question, the green of evergreens becoming underbellies of button mushrooms. Starting with the final poem in the book, I worked my way towards the first, copying each sestet into a red notebook in a red pen, and in the space between Wright’s lines, I would enter mine in purple.

And when rereading wasn’t enough, I disassembled every sestet in the book so that I might put them back together again: I translated each poem into its opposite, one by one, line by line. Some days, I would choose an antonym for each word of Wright’s, deferring any concerns of grammar and logic indefinitely, so ticking with unpaused breath became humming without stopped short-of-breath. Other days, I abandoned allegiance to Wright’s word choices and tried, instead, to rewrite the mood, feeling, or tone of the poem in question, the green of evergreens becoming underbellies of button mushrooms. Starting with the final poem in the book, I worked my way towards the first, copying each sestet into a red notebook in a red pen, and in the space between Wright’s lines, I would enter mine in purple.

I never tired of Sestets. Wright’s voice in these poems is easy, soft and low, funny, melancholy, smooth, wise. And I returned gladly to poems like “Cowboy Up” again and again:

I took time, a lot of time, with Wright’s sestets. Because part of every day that year found me reading or rewriting Sestets, it became my daily devotional, just like the sage green Catholic prayer book on my mother’s beside table. For my mother, the divine is routine. Her day, each day: she sets the coffee brewing, brushes her teeth, prays in the bathtub, feeds the cats, prays on her drive to work. Though no longer a practicing Catholic, with Sestets as my pocket prayer book, I located my reading and writing practice in the space of daily prayer, the space where the quotidian and the sacred meet, where our desires and fears reside together, where our hearts are meat on the grill. As a child, I fell asleep each night reciting the prayers I’d learned in school, in church, from my parents. Give us this day our daily bread.

Though I’m not sure it’s true, I heard tell that Wright wrote Sestets by composing a poem a day as he looked out across a deep valley towards the sundown smoke like a pink snood over the gathered hair of the mountains, the sun a garish hatpin. No wonder the book echoes in its content both the day-to-day and the everlasting, each poem a mini meditation on the inscrutable mechanisms of the landscape and the large heavens overhead. If you can’t delight in the everyday, he writes, you have no future here. And if you can, no future either.

These days, after recently reentering a world without a writing program schedule, my reading and writing practice feels untethered, in need of rethinking. I look to Wright for poetry that is both rooted in routine and reaches towards the sacred. Poetry that is otherworldly, extraordinary, charged with possibility. Writing, for me, needs to be a long-term relationship that feels, from time to time, like a blind date. I need to believe in the potential of each poem to speak a truth, to go to a place where the heart of the world lies open, leached and ticking with sunlight for just a minute or so.

*Italics indicate lines or adaptations of lines from Sestets.